The Board of Longitude 1714-1828

Peter Johnson

A brief history is given of the Board of Longitude, which was set up after Parliament offered a huge reward for discovering longitude at sea. It was one of the most interesting bodies in the history of British science and played a vital role in the development of navigation, astronomy, instrument design and world exploration.

Introduction

In 1714 Parliament offered a reward of £20,000 for a method of discovering longitude at sea. The Board of Longitude was set up to investigate claims by inventors and instrument-makers and to report back to the government. It later expanded its scope to include the improvement of general navigation, the design of instruments, the encouragement of world exploration and research into astronomy. The Board was also one of the prime movers in the foundation of the observatory at the Cape of Good Hope. It remained in existence for 114 years until disbanded by another Act in 1828.

The period was one of great impetus in the opening up of the world's trade routes and the creation of almost unlimited potential for exploration and colonisation, which would have been almost impossible without accurate longitude determination. The importance of the Board has not perhaps been fully appreciated.

The papers of the Board are kept in the archives of the Royal Greenwich Observatory (Ref. RGO 14/1-68). They form a great mass of material bound in 68 (mostly very large) volumes. An additional volume is kept at the Public Record Office (Ref. ADM 7/684). They include minutes of Board meetings, attendance of members, details of relevant Acts of Parliament, salaries, correspondence with inventors, accounts of the trials of chronometers, ideas politely described as impractical schemes, the log-books of several ships, the astronomical observations of Captain Cook's voyages, the founding of the Cape Observatory and material relating to the Nautical Almanac.

A detailed history of the Board can be compiled from the confirmed minutes of its 243 meetings, which were indexed by the present writer, backed up by the other material. Huge numbers of people were associated with the Board - astronomers, admirals, statesmen, instrument-makers, explorers, cartographers, publishers, mathematicians. Its work consequently covered a vast spectrum of activity, from perpetual motion machines to the mutiny on the Bounty, from the design of sextants to the early history of Australia. The whole formed a most interesting colourful episode which will certainly never be repeated.

Foundation of the Board

The latitude at sea could easily be determined from the altitude of celestial bodies, but the early sailors had no way to measure the longitude, other than by estimating the number of miles sailed east or west, which was often little more than inspired guesswork. The lack of method was increasingly felt in the seventeenth century and was, in fact, the main reason for the founding of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich in 1675.

Two particular incidents accelerated the founding of the Board. In 1707 a squadron under Sir Clowdisley Shovel ran aground off Scilly with the loss of some 2,000 lives: Britain's worst maritime disaster. Then in 1713 the mathematicians William Whiston and Humphrey Ditton suggested a scheme for determining longitude by anchoring ships along the main sea-lanes and firing a shell timed to explode at a height of over a mile. The time between the flash and the corresponding sound would give the distance to any ship within range. They first announced their idea in the Guardian (1713, July 14).

Although completely impractical it received widespread publicity and encouraged a petition to Parliament by several sea-captains and London merchants which suggested that Parliament should offer a prize for finding a solution. The government took this seriously and a Parliamentary committee was set up to report on the problem. Among others this included Isaac Newton, Edmond Halley and Samual Clarke, and the committee recommended that a reward should be offered for finding longitude at sea.

A Bill was presented in 1714 June For Providing a Publick Reward for Such Person or Persons as shall discover Longitude at Sea. It received the Royal Assent by Queen Anne on 1714 July 20, only 12 days before she died.

The Act offered rewards of up to £20,000 for discovering longitude at sea to within certain limits of accuracy: £10,000 if accurate to one degree of the great circle (60 nautical miles), £15,000 if to 2/3° (40 nautical miles) and £20,000 if to 1/2° (30 nautical miles). This sum was unprecedented by the standard of the day. By comparison, the Astronomer Royal's salary was originally only £100, rising to £300 under Maskelyne. It is estimated that £20,000 in 1714 is the equivalent of at least £1 million in the currency of the 1980s.

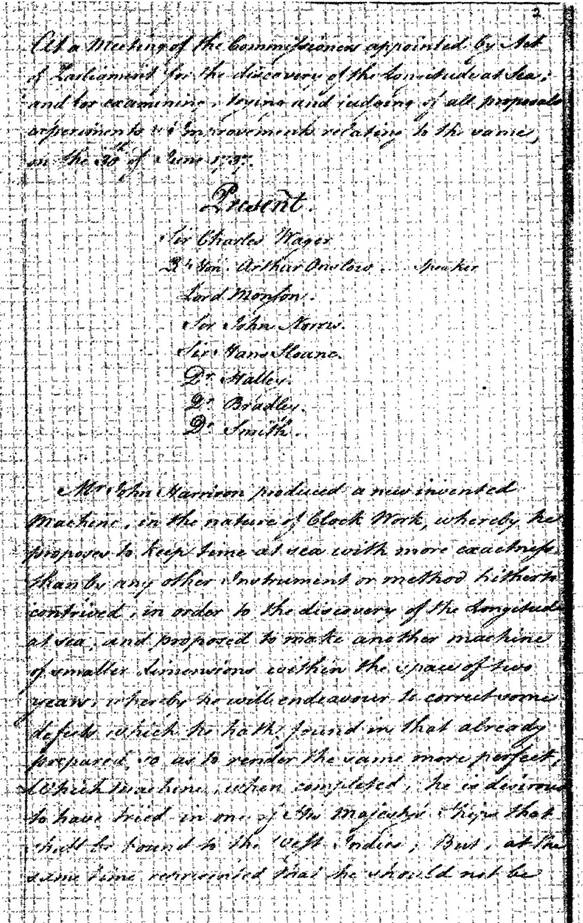

Figure 1 : First page of the confirmed minutes of the Board of Longitude, 1737 June 30. Mr John Harrison produced a new invented Machine, in the nature of Clock Work, whereby he proposes to keep time at sea with more exactness then by any other Instrument or method hitherto contrived, in order to the discovery of the Longitude at sea; and propose to make another machine of smaller dimensions within the space of two years....

Half the reward was to be paid if the method extended to 80 nautical miles from shore, the place of greatest danger, the other half if successful over a longer distance, such as a voyage to the West Indies. The method had to be practicable and useful at sea, a vague term which was to be the subject of much controversy later.

Small sums could be advanced towards schemes that seemed promising for further experimentation. If a method did not reach the listed limits of accuracy but was still considered to be useful, a smaller reward could be offered. These rewards were open to people of all nationalities and many applicants came from overseas, especially from France and Spain, the other two leading seafaring nations of the day. The reward also stimulated mathematicians and astronomers the world over to work on the problem.

Organization and meetings

The Longitude Act appointed a group of Commissioners who came to be known as the Board of Longitude. Their function was to consider the suitability of schemes and pass on their opinions to the government. They obviously had to be selected so that they were competent in dealing with such scientific and technical matters. They comprised admirals, the Master of Trinity House, the President of the Royal Society, the Astronomer Royal, professors at Oxford and Cambridge, and ten members of Parliament.

The full number was 22 but they never seem to have met all together at one time. Most of the early meetings had only seven or eight members and the average number was about 12. Commissioners were paid for their services. An Order of 1763 appointed a secretary at £40 a year, while the professors were paid £15 for each meeting. The sums gradually increased and Airy was paid a salary of £100 in the 1820s, quite a reasonable sum at that period.

Although the Board was created in 1714, the first 20 years or so remain rather obscure. They almost certainly met before 1737 though no record has survived.

The first known meeting for which minutes exist was on 1737 June 30 (Figure 1). The minutes of the early meetings were rewritten in 1762, a note being made of the disorder of the original papers, and under these circumstances a loss could be possible.

The fact that no practical method for finding the longitude was devised before Harrison and his chronometers and Mayer and his lunar tables came under discussion must have greatly reduced the activity of the Board. It is known that the plan of Whiston and Ditton was discussed by the Board and rejected; Ditton died in 1715 when the matter was still unsettled. Whiston made further attempts to devise means for discovering the longitude. In 1720 he published a new plan founded on the dipping of the needle, improved in 1721, but this too was rejected. A public subscription was raised in 1721 to reward him, the King himself giving £100 and the total was £500; the Board may have been partly instrumental in this.

The first few meetings for which minutes survive were held several years apart and generally coincided with the progress that Harrison was making with his chronometers. From 1760 they were held annually, with a peak of 10 in 1765. From 1776 they were fixed at three a year, increased to four in 1818. Meetings were always held at the Admiralty, originally on a Saturday, though this was later changed to Friday and then Thursday for the benefit of members living outside London.

On several occasions in 1803-1813 additional Extraordinary Meetings were held to discuss particular problems and they were held again in 1820 to consider the founding of the observatory at the Cape of Good Hope.

It may be noted that several other countries set up bodies to deal with the same general problems of navigation at sea, time-keeping and the publication of a nautical almanac. Thus in France the Bureau des Longitudes was founded in 1795 and still exists.

The Astronomer Royal was an ex officio member and almost always attended. In its active lifetime the Board had five, from Halley to Pond, while Pond's successor Airy also sat when Lucasian Professor at Cambridge. The shadowy Nathanial Bliss, by far the least-known of the Astronomers Royal, sat on six meetings. Maskelyne attended nearly all the meetings over 46 years and was the most important single person in its history, his years covering its most fruitful phase. The Astronomer Royal himself had the final say as to the suitability of schemes and instruments.

In the early days few Commissioners attended more than two or three meetings, but from about 1760 a pattern began to emerge of the more usual Commissioners. The names of those who attended most frequently included Admirals Isaac Townsend, Henry Osborn, John Forbes and George Pocock and Professors Anthony Shepherd, Edward Waring and Thomas Hornsby, as well as Joseph Banks (President of the Royal Society) and Nevil Maskelyne (Astronomer Royal). For several years these last two often met as a committee dealing with matters not discussed at a full meeting.

Joseph Banks joined the Board in 1772 and became the most important figure after Maskelyne. It was mainly through Banks' initiative that the Board was reconstituted by an Act in 1818 to increase the power of the Royal Society in the Board. As a result, from the late 18th century the admirals seldom attended, their places being taken by more and more scientific men. These included some of the most distinguished British scientists of the day, men like John Herschel, Humphrey Davy, William Hyde Wollaston and Stephen Rigaud. Over the last 30 years there was little turnover of personnel, possibly leading to a loss of enterprise, the same men tending to meet year after year.

In 1798 a committee was set up which met at Banks” house in advance of a full meeting to deal with accounts from publishers and booksellers, and consider and reject some of the more obviously useless schemes. Other committees set up included one For examining Instruments and Proposals, one of Resident Members and a Committee of Accounts for the complicated financial dealing of the Board.

Figure 2 : John Harrison (1693-1776), winner of the £20,000 Longitude Prize.

The solution to the longitude problem

The basic theory behind discovering longitude is simplicity itself. As each 15 degrees of longitude corresponds to a time-difference of one hour, it is only necessary to compare the local time (using the Sun's highest altitude to determine noon) with the time at Greenwich (or any other reference meridian). One thus had to have on board a timekeeper from which Greenwich time could be found to the requisite precision. The difficulty was to design such a chronometer which could keep time accurately over months on board ship, with extremes of heat and cold, damp or drought.

The successful inventor was John Harrison (1693-1776), the man who solved the longitude problem and who eventually won the £20,000 prize (Figure 2). The early years of the Board were dominated by Harrison and his chronometers, his problems, the testing of the timekeepers and his struggle to obtain the reward. The earliest surviving confirmed minutes of 1737 open with the words Mr John Harrison produced a new invented machine, in the nature of Clock Work, whereby he proposes to keep time at sea with more exactness than by any other instrument or method hitherto contrived. The trials went on for decades, Harrison's work being encouraged on many occasions by small payments from the Board.

It was his fourth timekeeper (a large watch, called H4) which was taken on a trial to Jamaica and back in 1761-62. Although Harrison claimed that H4 more than complied with the 1714 Act, the Board disagreed and insisted on a second trial, in which H4 also performed very well.

The Board was still not fully satisfied, half only of the reward was paid and on condition that Harrison disclosed the construction so copies could be made. The first of these was built by Larcum Kendall (K1) and was sent with Captain Cook on his second voyage. Despite glowing praise from Cook, Harrison had to appeal to King George III before he was paid the full reward in 1772, at the age of 78. The often heated exchanges between Harrison and the Board are well-preserved in the archives.

At the same time as the Board was dealing with Harrison, another method of finding longitude was being acquired. The Moon moves quite slowly across the background stars and its position can in theory be used as a means of finding Greenwich time. The difficulty here was that the Moon’s motions were not known sufficiently accurately for tables to be drawn up months or years in advance to determine longitude with sufficient precision.

In 1755 the Board received accurate lunar tables from the German mathematician Tobias Mayer. They were derived from equations by Leonard Euler and the observations of Mayer and James Bradley (Astronomer Royal 1742-62). These were improved by a second set of tables which Mayer bequeathed to the Board on his death in 1762. They allowed longitude to be found to within a few nautical miles and also permitted the position of the Moon to be calculated several years in advance.

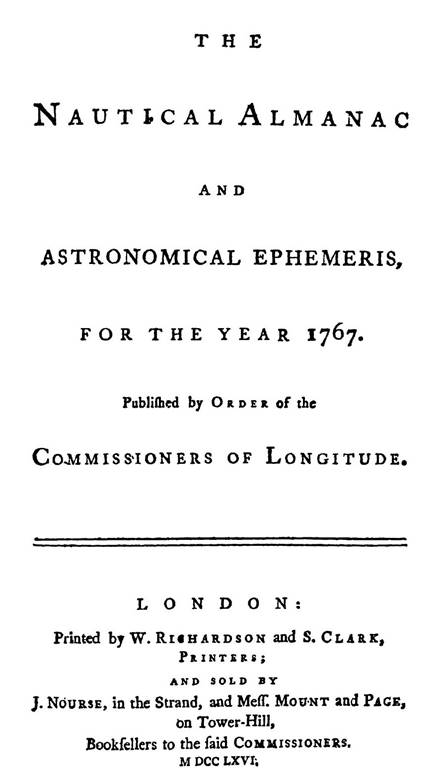

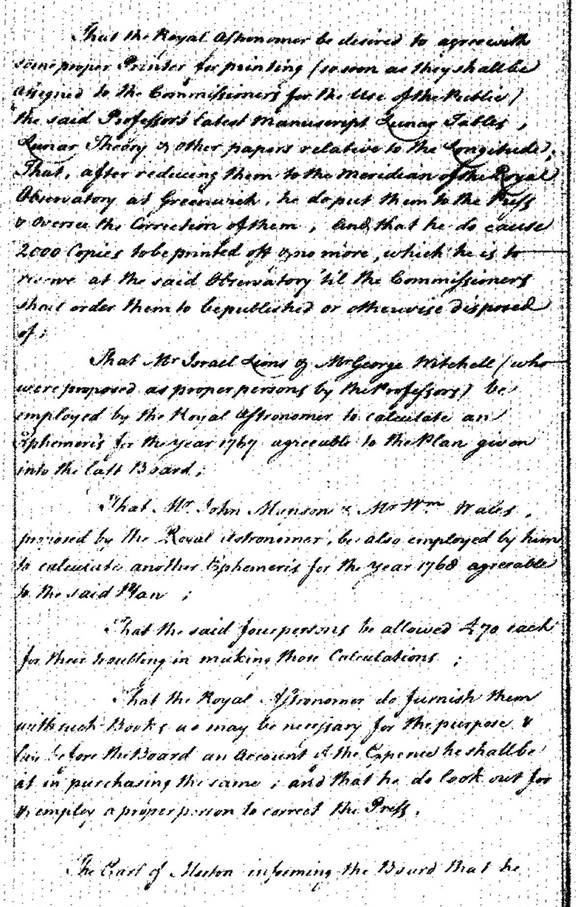

The Board recommended the publication of an annual almanac giving the position of the Moon every three hours, and other information, from which longitude could be found. The Nautical Almanac was first published in 1766, for 1767, most of the planning being done by the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne (Figures 3 and 4). The computations of tables and the printing of the Almanac remained a major interest of the Board.

Attracted by the enormity of the reward the Board received schemes from hundreds of applicants. Some were scientifically sound but impractical at sea. For years the Board toyed with the idea of using the times of the eclipses of Jupiter's satellites to determine longitude, but unfortunately they were almost impossible to observe on a moving ship. An inventor claimed to have designed a marine chair which would keep horizontal on ship and received encouragement from the Board for some time. Other methods were unscientific and a few just ludicrous. These were politely termed impractical schemes. Though Gould has perhaps exaggerated when he stated the Board at once became the immediate and accessible target of every crank, swindler, fanatic, enthusiast and lunatic in or out of Bedlam, yet a few passages from the minutes are worth quoting.

25 January 1772 - A person who calls himself John Baptist desiring to speak with the Board, he was called in and showed them some schemes and drawings of figures which he desired they would enable him to publish; he was informed it was not in their power.

13 June 1772 - A Memorial from Mr Owen Straton was read, proposing a method of finding out the Longitude by means of an instrument of his invention, and the said Mr Straton who was attending being called in, and it appearing that the instrument proposed is a Sun Dial, he was told it could not be of any service.

3 June 1824 - Mr Lupton's letter requesting the possession of a secret method of finding the longitude was considered as not requiring an answer.

The Board eventually made a ruling that before an idea was submitted the petitioner must first obtain a certificate from some person in authority as to its usefulness. Some of the schemes had little or no connection with longitude at all. These included squaring the circle and perpetual-motion machines.

Figure 3 : Title page of the first edition of the Nautical Almanac.

During its history the Board paid out (or recommended that Parliament should pay) grants and rewards to some 60 individuals. The major prize of £20,000 was paid to John Harrison (in about a dozen installments over 35 years) for his marine chronometer. £3,000 was paid to the widow of Tobias Mayer (the Board had recommended £5,000) and £300 to Leonard Euler, for providing the basis for the lunar tables in the Nautical Almanac.

Maskelyne himself received nothing for overseeing and organizing the Nautical Almanac as this was considered part of his duties as Astronomer Royal. He handled a total of some £1,000 for paying computers, stationers and printers.

The majority of the other recipients were instrument-makers who made some improvement in the design of chronometers, sextants, quadrants and other navigational instruments. These awards were in the order of a few hundred pounds, worth of course many thousands in modern terms. Persons who provided ideas for improving the Nautical Almanac or who supplied more accurate tables were also rewarded.

People whom the Board considered to be specially worthy of recognition for other reasons also received a payment. These included Mrs James Cook, Mrs Nathaniel Bliss and retired computers of the Almanac.

Figure 4 : Arrangements for printing the first edition of the Nautical Almanac (meeting 1763 August 4). That the Royal Astronomer…do cause 2000 copies to be printed off & no more.

Later years of the Board

With the award of the main prize to Harrison and the foundation of the Nautical Almanac the Board had fulfilled its role under the 1714 Act. However, it was kept in being by a new Act of 1774 which moved the emphasis away from longitude to navigation in general. The scope of the Board became much wider. Improvement and refinements of navigational instruments were a main concern. Chronometers were improved by men like Thomas Mudge, John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw, and sextants were refined by using an artificial horizon. Greater accuracy was achieved in the technique of ruling the scale divisions on instruments, notably by Jesse Ramsden.

The Board also entered into such areas as the accurate measurement of ships’ tonnage, meteorology, magnetism and the production of accurate naval charts. It was mainly for the latter reason that the Board became increasingly linked with world exploration through the great voyages of discovery of the late 18th and early-19th centuries. Many volumes of the Board's papers deal with these voyages, undertaken between 1763 and 1824, partly to obtain accurate naval charts, partly to test chronometers and partly to make observations of the southern skies, thus facilitating navigation.

The Board loaned out chronometers to seamen of the standing of James Cook, William Bligh, Matthew Flinders and George Vancouver, indirectly playing a considerable part in the development of the future British Empire. The explorations round Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific owed much to the Board, most notably the second and third voyages of Captain Cook, many of whose papers are kept in the archives.

The documents record the misfortunes of Matthew Flinders, his shipwreck and subsequent imprisonment on Mauritius. The papers also contain references to the mutiny on the Bounty and the search for the mutineers. Several ships’ log-books are kept in the archives, as well as astronomical performed out on the voyages, astronomers being employed by the Board to carry out observations and to test chronometers and other instruments.

The re-organization of the Board in 1818, already mentioned, which increased the influence of the Royal Society, may have been one of the reasons why the Board in 1819 offered rewards for discovering the north-west passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, or for progressing towards the North Pole. Rewards were on a sliding scale, similar to that for discovering longitude, as follows.

For reaching longitude 110° west £ 5,000

For reaching longitude 130° west £10,000

For reaching longitude 150° west £15,000

For reaching the Pacific by a North-West Passage £20,000

For reaching latitude 83° north £ 1,000

For reaching latitude 85° north £ 2,000

For reaching latitude 87° north £ 3,000

For reaching latitude 88° north £ 4,000

For reaching latitude 89° north £ 5,000

The first of these rewards was claimed by a party commanded by Captain William Parry in the ships HMS Hecla and Gripa. For reaching 113° west in 1820 it was paid £5,000. No further claims were made before the Board disbanded.

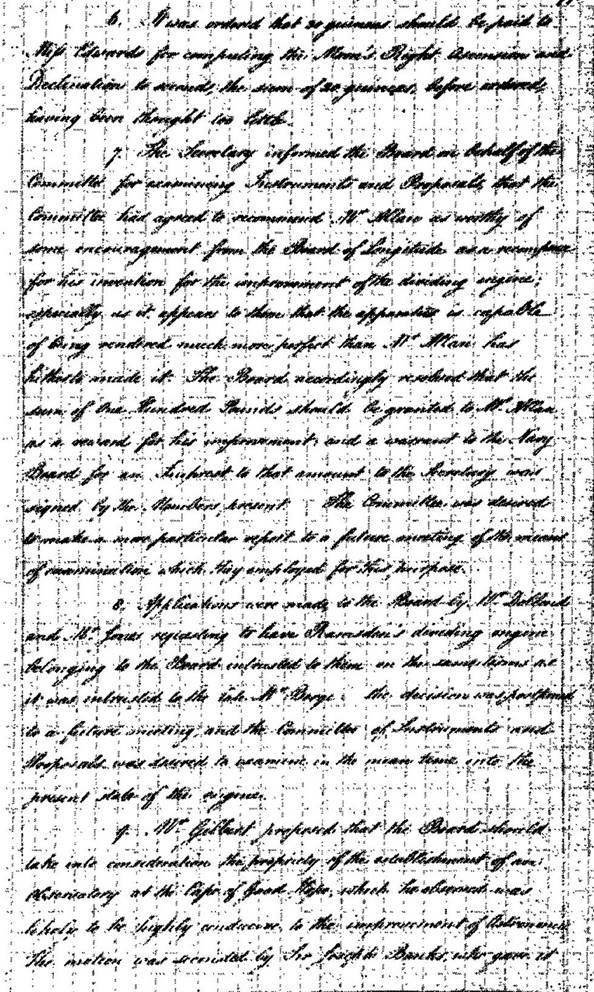

The last major project undertaken by the Board was the foundation of the observatory at the Cape of Good Hope. Its aim was to increase the knowledge of the southern skies and improve navigation south of the equator. The first mention is at the Board meeting of 3 February 1820 (Figure 5). Mr [Davies] Gilbert proposed that the Board should take into consideration the propriety of the Establishment of an Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope, which he observed was likely to be highly conducive to the improvement of astronomy. The motion was seconded by Sir Joseph Banks, who gave it as his opinion than nothing could more essentially promote the glory of this country, than to be the foremost in such an undertaking. The founding of the observatory is well-documented in the Board’s papers.

Figure 5 : Confirmed minutes of meeting 1820 February 3. No 6. - Ordering 30 guineas to be paid to Miss Edwards for computing Moon's places. No 7. - Granting £100 to Mr Allen for his improvement to (Ramsden's) dividing engine. No 8. - Application by Mr Dollond and Mr Jones for the loan of Ramsden's dividing engine. No 9. - Proposal for the erection of an observatory at the Cape of Good Hope.

Disbandment of the Board of Longitude

By this time, though, the role of the Board was becoming even less well-defined and uncertain. It was increasingly linked with the pure astronomy at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. The ardour of the great voyages of discovery had cooled, partly because of the political situation, as reflected in the 6 year imprisonment of Mathew Flinders. Areas of work into which the Board might have moved were taken over by two societies formed about this time, the Astronomical Society of London (later the Royal Astronomical Society) and the Royal Geographical Society.

Its remaining responsibilities were subsumed into the work of the Royal Observatory, the rating of chronometers in particular proving a serious drain on the time and resources of John Pond and his small staff. The books and papers of the Board were also transferred to the Royal Observatory. A tangible reminder is the very fine collection of rare books on voyages of discovery in the 18th and 19th centuries in the Rare Book Collection at the Royal Greenwich Observatory.

The Board of Longitude was finally dissolved on 1828 July 15 by Act of Parliament. It had been in existence 114 years. Nevertheless, in its time it had been a colourful and influential body. The rewards offered in 1714 stimulated many advances during the next 114 years over a very wide field, just as Parliament hoped would happen. Progress in astronomy worldwide, as well as navigation and horology, was greatly furthered by the Board's activities. The Board of Longitude was certainly one of the most important and interesting bodies in the development of science and technology of that period.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my thanks to Janet Dudley, formerly Librarian and Archivist of the Royal Greenwich Observatory, for my initial interest in the Board of Longitude and allowing me unrestricted access to the archives, and to Professor A. Boksenberg, the Director.