The Simpson Desert A.H.D. Levelling Survey – 1970

This article titled The Simpson Desert A.H.D. Levelling Survey – 1970 was written by John Gibson and appeared in the Institution of Surveyors, Australia, S.A. Division newsletter TIELINE (December 1997, Volume 10, No.8). It is reproduced with permission.

The vast Simpson Desert, a unique part of Australia, lay undisturbed for millennia, plus a century after European settlement, until that relative of adventurers and explorers, the surveyor made a tangible mark on the terrain. The year was 1879, when Augustus Poeppel surveyed the Northern border of South Australia, using mile posts cut from Mulga trees, 6 inches square and four feet high with the mileage neatly chiselled into the wood together with the Government broad arrow. Ninety one years later some were still standing on the dunes weather worn and seen by few since the day they were placed.

Not much happened until exploration for oil and minerals was undertaken and surveyors were needed to establish co‑ordinates, both horizontal and vertical for mapping purposes.

In 1963 a dozen people worked for 3 months on a Geodetic traverse, with trig stations up to 20 miles apart to establish a grid system for French Petroleum who were doing exploratory drilling through the desert.

Surveyors who continued that task during the years to 1968 included Peter Simmons, Bill Randle and Bill Haylock, and I believe Brenton Burford as a cadet on his very first excursion. He probably wondered whether he was on the moon at the time! Much of the work was done at night taking star observations, and just as well, because during a three week period the temperature did not fall below 90°F at night, and generally reached 120°F during the day. Humidity was low which made the heat more bearable.

By 1970 third order levelling had been completed over the continent except for the Simpson Desert link between the Alice Springs railway line at Pedirka and the township of Birdsville.

Yours truly drew the straw for that final contract, and this is the story of that levelling survey, done for the Department of National Development.

The desert is uninhabited and accessible only from the west, so the survey party of four; surveyor and three staffmen, had to be self-sufficient for the duration of the crossing. My assistants were Roger Wreford, retired radio technician and bank officer, Ron Burge, a miner from Coober Pedy, and Larry Yeates a rigger from Port Lincoln.

All supplies from basic food, water, bedding and petrol to spare parts and even shoe laces, had to be gathered and packed. The bench marks had already been placed at three mile intervals by people from the Woomera army base using heavy equipment. It was interesting that the half-track machines had performed well in the Sahara Desert but the Simpson Desert sand was finer and wore out the steel tracks. We used three ex-army short wheel base Land Rovers with radial tyres and one International utility, fitted with 8.50 x 16-10 ply tyres, loaded everything including a spare set of wheels with Michelin Sahara tyres for the sand, and set off. At Clare the vehicles were checked on a weighbridge, two and a quarter tons per Land Rover, five and a quarter tons for the International, in all 12 tons gross weight. From Clare, through Marree, Oodnadatta and 80 miles on to Pedirka where some railway gangers gave us coffee and biscuits, then eastward to the wilderness. We would not see another person for almost two months.

Twenty five miles across desert debris of hard silicate rocks coated with red manganese oxides, similar to Sturt's Stony Desert in the east, along eroded wheel tracks with ruts to three feet deep, brought us to Dalhousie homestead.

From there the land drops from a dry stony plain to a long wide valley, with fresh water hot springs, date palms, tea trees, bamboos and birdlife, leading into Spring Creek, an ancient geological tributary of the Finke River. The area known as Witcherie Bog comprises soft damp black soil and within minutes the Inter utility was sitting on its chassis, mud up to all four axles, half an hour before sundown. The Land Rovers, with soft walled radial tyres had managed to cross the soft patch despite their weight, but the utility with hard tyres broke through the crust and quickly sank. With a dark sky and chance of rain it was imperative to move quickly, so two Trewalla jacks, mechanical monsters capable of a two foot lift, were placed on wooden platforms, lifting each wheel into the air. Strips of conveyor belting were placed under the wheels, the vehicle let down and we were ready to move forward.

All three Land Rovers were connected in series by heavy steel cables, the rear one cabled to the International and at a signal all four vehicles pulled together; we raced ahead slowly in low gear for several hundred yards on to firm ground, as the sun set behind us. The conveyor belts were collected, Land Rovers separated and the convoy moved on. We crossed the Finke River bed and climbed on to the sand at the beginning of the Simpson Desert where we had tea at sand dune number one. We then climbed into our bed-rolls and had the untroubled sleep of the truly innocent.

Aerial photo mosaics showed the positions of bench marks which were listed according to sand ridges crossed, and the last ridge numbered 1101. While they all looked similar on photos they varied greatly on the ground, from three feet high to one hundred feet high near the eastern edge.

For some unknown reason ridges join each other only on the northern ends, never the southern ends.

The last watering place, a few miles from Finke River to Purni bore, an exploration drill hole which struck water at 1 mile deep instead of oil, gave us hot and cold showers, literally. The water bursts from the ground at boiling temperature, then shoots high into the air before falling back to earth, either hot or cold depending on the wind direction. (Giving alternatively a hot or cold shower in quick succession). From Purni, one hundred and eighty miles from Birdsville, we soon reached the high sand hills, with no chance of turning back, as the eastern side of each ridge was free-falling fine sand driven by the prevailing westerly winds. At this point the Inter wheels were exchanged for larger ones with Michelin sand tyres fitted, and we moved forward feeling somewhat alone in the world. We had more than 800 sand ridges to cross over to Sturt’s Stony Desert and the Birdsville track.

The work proceeded steadily at the rate of one and a half miles forward and one and a half back, using triangular half inch thick steel plates, triple spiked with central bolt for a turnpoint. Each page of the issued level books was signed and dated daily, and I chose to enter the readings, levels and stadia distances with an Indian ink pen. No rubbing out was possible, nor was it needed. The procedure was to level forward half way to the next bench mark, place a wooden peg at the turn point, level back to the starting point where all vehicles were left, then check the two runs for accuracy. All vehicles were then driven forward to the peg, and the procedure repeated to the next bench mark. If a section was outside acceptable limits the l'/2 mile leg had to be repeated. Fortunately that was a rare event.

By now it was early June 1970, the daily temperature was 70°F; every day was a pleasant autumn weather. As surveyor I worked every day for eight weeks, two men worked with me, while the third had his day in camp, preparing lunch and evening meal, and resting. Thus in the process I covered every step of the desert in each direction while each staffman covered two thirds of the distance on foot.

At this time we were seeing wild camels from time to time, as many as eight in one group, and came face to face with a mole and two cows standing twenty yards from us in the hollow between dunes and we looked at each other for a full minute before they decided to move away - fortunately for us, since it was a mile back to the vehicles. One group wandered right into camp one morning, satisfied their curiosity and went on their way.

"Soft sand is very hard on axles, especially when low range four wheel drive is used - the engine will not stall and the vehicle cannot climb out of the sand so the axle breaks. Generally it is the shorter of the two rear axles which breaks since the longer one is able to twist further before reaching its limit and snapping."

By the middle of June our three spare short axles for the Land Rovers had been used and when a fourth one broke it was a problem. Axles usually snap near the differential which has to be removed to take out the broken piece. Unless the problem could be solved it would mean abandoning the vehicle in the desert, so an attempt was made to repair the axle by welding the pieces together, reversing the axle with the good end inner-most and driving as gently as possible. This makeshift repair lasted for twelve miles over the dunes before breaking again. I still had a spare long axle, but this protruded from the wheel eight inches or so. The problem was therefore to tie the end of the axle back on to the wheel, but how?

Fortunately French Petroleum had left 2" water pipes with flags attached poking ten feet into the air as markers, and the last one seen was only a mile or so behind us. Two of the men walked back to retrieve it, and with the oxy torch I fashioned a sleeve to fit over the axle, splayed the ends to match the wheel bolts and cut holes for the wheel bolts with the torch. This contraption was slid over the axle, bolted to the spliced axle cap at one end, and to the wheel at the other end, all holes and gaps then filled with Plastibond to keep oil in and sand out, painted red to protect our shins and with crossed fingers and a prayer we put it to the test. The engine turned the differential, which turned the axle which turned the sleeve which turned the wheel. The ‘Roman Chariot’ axle completed the crossing for the remaining four hundred and fifty dunes, and in fact brought us back to Adelaide without giving any trouble at all.

The ‘Roman Chariot’ axle.

We arrived at Poeppels Corner on 21st June 1970 with 90 miles to go to the Birdsville track. I found out later that another surveyor who left his mark on this state, Mr. C.L. Alexander my first employer, departed this world at that time.

Four miles east of Poeppels Corner lies one of a series of claypan lakes overlaid with a sheet of salt and gypsum dust forming a crust half an inch thick, giving the appearance of a hard surface.

In reality a deep bed of soft black mud lurks beneath to the peril of heavy motor vehicles. The lake is two miles wide at the crossing place but fifteen miles long from north to south making a detour impractical. We started crossing at dusk, the Land Rovers moving off in line, followed by the International in fourth place. I discovered straight away that the lights weren't working but there were three sets ahead to follow, with no obstacles to avoid so I continued.

Soon the Rovers began to break through in soft patches and dispersed to find their own way on separate new tracks. This left me following three weaving light patches surrounded by blackness as the heavy Inter began breaking through the crust, slowing and threatening to sink and stop, which would have meant a permanent stop for the utility. Starting in low range fourth gear, back to third then second at full revs, needle on boiling point, cabin full of fumes the Ute stumbled on to dry sand and stopped, engine stalled and making hot crackling noises.

Later I walked back on to the silent lake looking like a sheet of ice in the moonlight and measured the depth of wheel ruts, generally nine inches, up to 15 inches where the wheels had broken through. We slept that night on the home side of the dry lake and woke in our sleeping bags at dawn, motionless air at 28°F but no frost, as there was no atmospheric moisture to condense and freeze.

A little further on, at 16 minutes past 8 on the night of 27th June we were treated to a most spectacular sight. The air is very clear in the outback, the night sky bright with stars and constellations, meteors are seen often, with satellites almost a nightly occurrence. When a bright light appeared low in the northern sky we thought it was another meteor, soon to burn out.

This one grew larger and brighter moving at a leisurely pace until the land all around was like a floodlit field, trees half a mile away bright as though in daylight. As the object passed overhead it looked like a long passenger train with carriage lights, occasional pieces of white material breaking away from the sides, all followed by a stream of white light similar to a comet tail.

It continued at a steady pace in absolute silence until it moved low in the southern sky, turned red, then faded and disappeared, leaving us standing alone in the dark with only the stars for company, exactly as we had been a mere minute earlier. Next morning we checked with the Royal Flying Doctor Service at Port Augusta on the two-way radio and were amazed to discover that no-one else had reported the event. We appreciated then how remote we really were from the inhabited world.

We had not seen another person since leaving Pedirka, but levelling along the old border fence, we came upon three native stockmen on horseback who almost slipped from their saddles in surprise. The elder looked at us, looked westward, scratched his head and said 'Where's your traffic?' It was all too hard to explain, so they trotted off eastward, possibly feeling they might be in some kind of danger.

On 15th July 1970 we topped sand dune 1101 and saw Birdsville seven miles away. Larry's Land Rover pulled itself over the top on its remaining two cylinders and on 16th July we tied to the final bench mark at the school house gate, two hundred and twenty miles from the first dune at Finke River.

These days, so I am told, hundreds of people pass through in either direction each year. I have never returned to see it all again but prefer somehow to remember the Simpson Desert the way it was then.

The following photographs of John Gibson and his assistants on various outback surveys were kindly provided by Mrs Lorna Gibson :

|

|

|

|

Gibson’s assistants (L-R) Roger Wreford, Ron Burge and Larry Yeates at the start of the sandhills during the 1970 Pedirka to Birdsville levelling traverse. |

1970 levelling traverse party at Poeppels Corner (L-R) Larry Yeates and Ron Burge. |

|

|

|

|

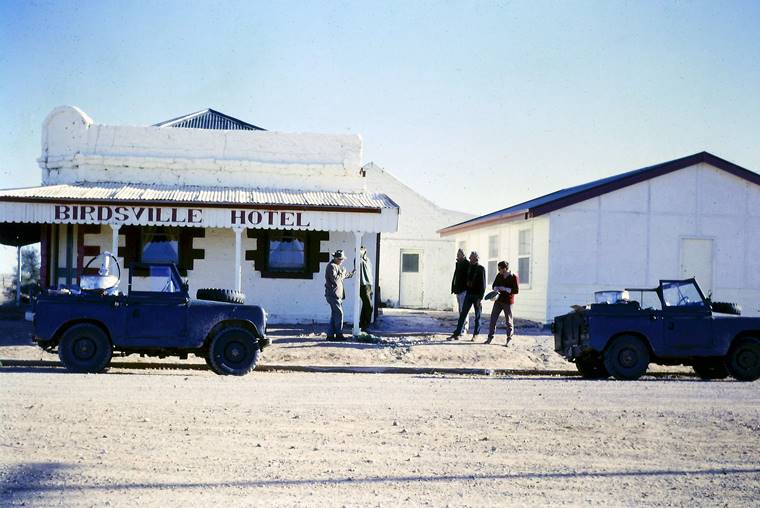

1970 levelling traverse party at Birdsville on completion of the levelling from Pedirka. |

Roger Wreford holding a levelling staff with a sea of flies on his back. |

|

|

|

|

Eyre Highway engineering survey party thought to be (L-R) Merv Sedunary, two chainmen from New Zealand (Bruce and Richard each with a levelling staff), John Gibson and Roger Wreford. |

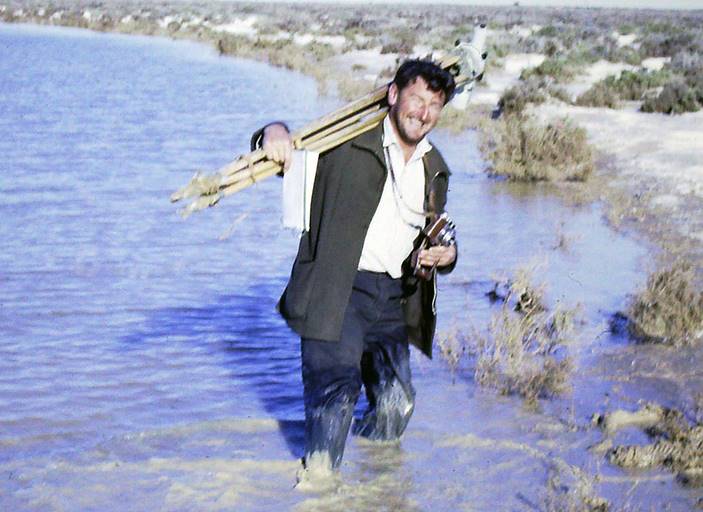

John Gibson with level and tripod on his shoulder, carrying fieldbook and camera, negotiating his environment. |

The following text appeared in the Adelaide press in the 1970s. It is reproduced with permission.

Surveyor John Gibson of Hove aroused the curiosity of many people following a report that he has walked across the Simpson Desert twice and counted 1,101 sandhills.

"First of all I didn't sling a swag on my back and amble 300 miles over the sandhills and back again.

My walking 'marathon' if you want to call it that was a planned survey during which I walked three miles, walked back to my Landrover, drove three miles and then repeated the procedure."

His survey for the Department of National Development was a national grid levelling system. It took seven weeks from Oodnadatta to Birdsville and the purpose was for utilisation of oil searches.

And about those 1,101 sand hills. "I didn't count them as I walked. I had an excellent aerial map and numbered them from that," John said.

Because of the back tracking, John walked a total of 460 miles.

Gibson's support team consisted of a radio operator and two drivers and their vehicles were Landrovers and a four wheel drive utility.

The party set out from Dalhousie and the survey was begun at Mokari.

The way the survey was conducted was for Gibson to walk three miles, take measurements of the sandhills then walk back to the vehicles.

The party would then drive the three miles Gibson had crossed on foot, and the exercise would be repeated.

Between Dalhousie and Birdsville, the survey party crossed 1,101 sandhills.

John Gibson planned his Simpson walk from shoelaces to two tonnes of water, food, fuel and spares through the whole range of expected and the unexpected.

His team: Roger Wreford, radio operator, Ron Burge, opal miner, and Larry Yeates, a rigger from Port Lincoln.

Some of the sandhills are from fifty to one hundred feet high. John Gibson believes the last veil should be lifted from the notorious desert.

"It is a place of beauty and character.

Dalhousie Springs: Small natural lakes surrounded by shrubs, small trees, bamboos and occasional date palms... small fish which surrounded us and nibbled our skin while we swam in the tepid water.

‘Witcherie bog', where the vehicles were roped together like mountaineers, but with steel cable so they would not sink in the treacherous mire.

Purni bore...last water before Birdsville that went flying into the air from artesian depths to return to the ground as a warm shower which no one wanted to leave.

Wild camels... they followed the surveying party like dogs, standing about watching the team work.

The morning of freezing temperature without frost because there was no surface moisture in the desert.

A particularly eerie night... "The land grew brighter until it resembled a floodlit field."

This remarkable object (a meteor) passed overhead like a great train in the sky with a brilliant white light at the front and white hot pieces breaking away from the sides.

So it continued in absolute silence...

Yet for all that it seemed to have filled the world apparently no one else had seen it, for a radio check with the Flying Doctor base next day revealed there had been no other report of the phenomenon.

Thanks to Mrs Lorna Gibson and her son Wayne Gibson for their kind assistance in supplying the photographs and papers used in this article.