Broken Hill Triangulation 1954

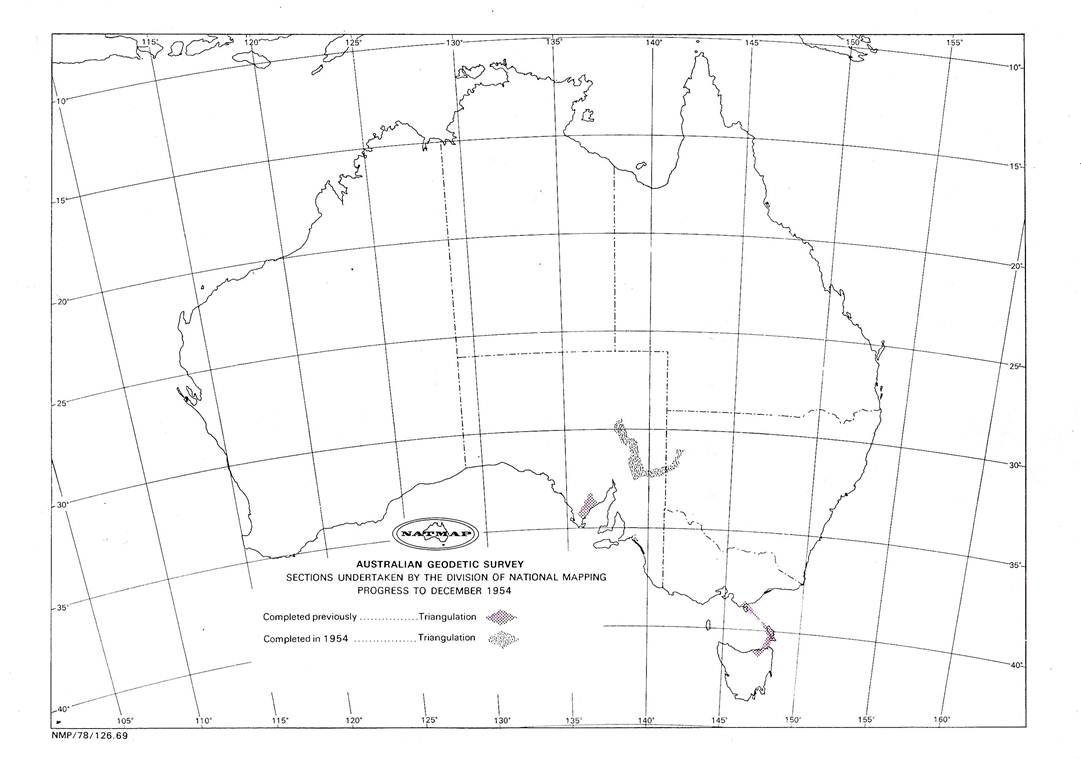

Nineteen fifty four was to be the first year of “the great leap forward” of the Geodetic Survey of Australia, instigated by the National Mapping Office. Two important events were to take place early in the year.

An order had been placed in 1953 for an instrument called a Geodimeter. This was the first distance measuring equipment which could provide distance measurements of a suitable accuracy for geodetic survey. The equipment was expected to arrive in Australia from Sweden in the autumn of 1954.

Also Colonel H.A. Johnson, Officer in Charge of the Royal Australian Survey Corps Training School at Balcombe, Victoria was to join the National Mapping Office in February as Senior Surveyor and would take charge of geodetic surveys. He was well known to the Director and the Chief Topographic Surveyor; he had been expected about twelve months earlier but had been unable to leave the Army at that time. It was known he was a man dedicated to seeing the Geodetic Survey of Australia completed and would be single-minded in pursuing that objective.

However the immediate concern as 1953 drew to a close was the pressing need to reconnoitre and observe early in 1954 a triangulation scheme for mapping purposes covering the area around Broken Hill and the Barrier Range. This was once again required by the Bureau of Mineral Resources.

Of the survey party which had commenced the first triangulation scheme on Eyre Peninsula in late 1951 only one observer and one field assistant remained at the start of 1954. However E.J. Caspers who had been on office computations since the Bass Strait triangulation became available again and as field assistant W.J. Dingeldei had been given considerable theodolite training, it was considered that three observing parties could be mounted if three new field assistants were engaged. The Director, B.P. Lambert, would do the reconnaissance and E.J. Caspers would lead the field party until the arrival of the new Senior Surveyor. Two short wheel base Land Rovers with trailers (long wheel base Land Rovers were not being manufactured at that time) and one Morris four wheel drive vehicle were available for transport.

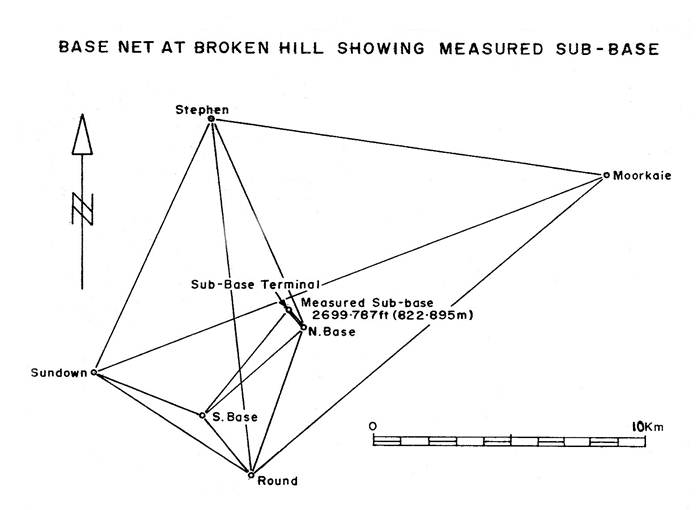

At that time the Broken Hill area was isolated from any triangulation chains; the two nearest schemes being the Army primary triangulation in the Peterborough - Orroroo - Carrieton area of South Australia and the old NSW Lands Department triangulation near Cobar, NSW For this reason the Broken Hill scheme would have to incorporate a classical base line and base net triangulation to expand the measured base. It was hoped to measure a very short base for preliminary computations and then measure a longer base, or alternatively measure the side of one of the triangles, with the Geodimeter when that instrument came into service.

During the reconnaissance twelve main stations were selected, plus four stations in the base net and two third order points for Bureau of Mineral Resources purposes. On the completion of the reconnaissance a short base was measured with a 300 foot steel band. This was done under the supervision the Director, who once this task was completed had to return to Canberra for an important SEATO conference. He appeared to enjoy his return to traditional triangulation survey reconnaissance and during his short stay easily fitted into all field party routine.

Figure 1 shows the triangulation base net close to Broken Hill, the sub‑base of 2699.787 feet was measured to enable preliminary computations to proceed.

Figure 1 shows the triangulation base net close to Broken Hill

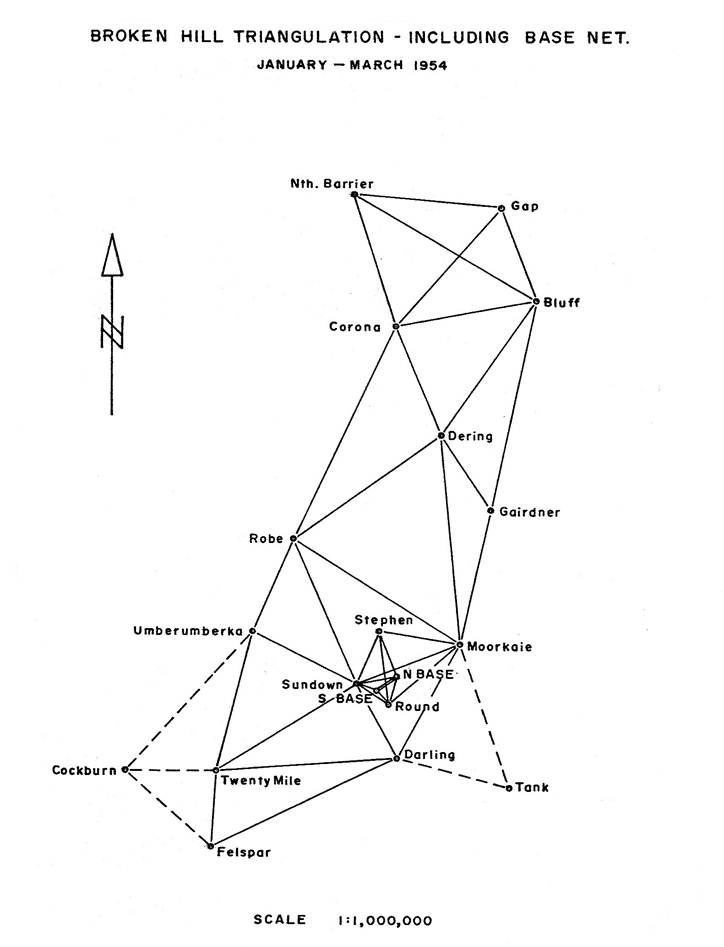

The line North Base - South Base was never physically measured, instead when the Geodimeter becomes available later in the year one aide of a triangle (the line Felspar - Twenty Mile) was measured. Figure 2 shows the full Broken Hill triangulation scheme observed between January and March 1954. Later on, for comparison purposes, the Geodimeter value of the line Felspar - Twenty Mile was used to calculate a value for the measured sub-base; the comparison between the value so obtained and the actual measured distance was approximately 1: 50,000.

One other “first" for National Mapping at this time was the laying down of calico strips in the form of a cross centralised on each station mark before the actual aerial photographs were taken by the contractor, Adastra Airways. This has been the only time to date that National Mapping had been able to have targeted station marks appearing on the actual mapping photography.

Observing now started; as there were only three observing parties, each of two persons, and all observing was to lights, the work had to be completed triangle by triangle. However the area is ideal for triangulation as there are numerous hills and most are steep enough to provide a good “drop away” which helps the steadiness of the lights. The triangle closures were good.

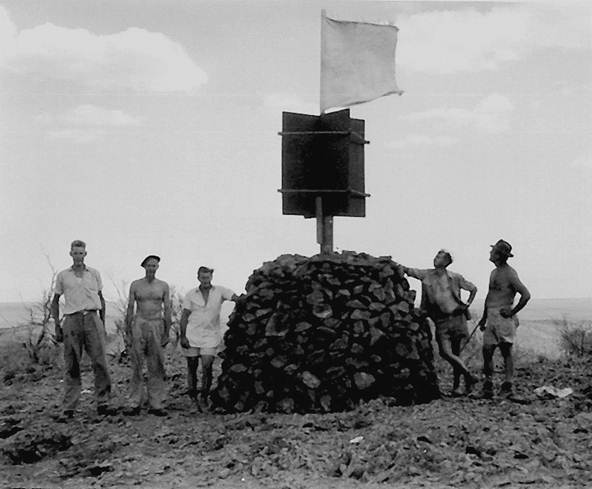

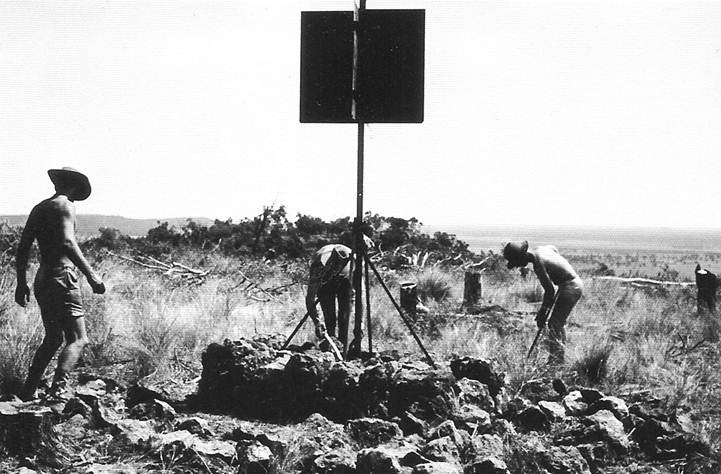

The base net observing had been completed and also the main figure around Broken Hill, when Senior Surveyor H.A. Johnson arrived. He brought another Morris 4 x 4 vehicle. On examining the task in hand he decided that the best approach was to beacon all remaining hills to enable work to be speeded up and most of the observing done to beacons in the daylight. Cairns were to be built centrally around twelve foot oregon poles with square vanes.

At this time, wartime shortages of building material were still evident so some difficulty was experienced in obtaining sufficient material. Sheet iron was in short supply for vanes and Masonite had to be used as a substitute; cement was also scarce. However eventually sufficient material was located.

Figure 2: Full Broken Hill triangulation scheme.

Cairn building was a new experience for the field party. Firstly a huge amount of rock had to be collected mainly by levering it out of the ground close to the building site, using a crowbar. The station mark was then emplaced (normally a half inch diameter copper tube set in concrete). A circle about eight feet in diameter was carefully marked around the station mark and large flat rocks were firmly emplaced as a base, their outside edges touching the circle. A second layer of rocks was built on top of the base rocks, overlapping the vertical joins in the base rocks as a bricklayer builds a wall. This outer wall was built about four layers high, then the pole with vanes already attached was placed directly over the copper tube (a protruding nail in the bottom centre of the pole ensured this). The pole was then held upright by two persons while the rest of the team threw in small and medium rocks as quickly as possible to firm up the pole. Once the rock fill reached the top of the base wall, the pole was normally firm enough to stand upright on its own and yet have sufficient “give” to enable moving it until perfectly plumb. Plumbing was done by standing well back and eyeing the edge of the pole for verticality against a plumbob string, the plumbob being held at arm’s length. If two persons “eyed” the simultaneously from two positions about 90º to 120º apart, adjusting any lean was easy.

The wall was now continued upward gradually tapering in, and the “fill” rocks kept level with it, the pole being continually checked for verticality until it was quite firm. The finished cairn was about six to seven feet high. Heavy leather workmen' s gloves were found to be a necessity for cairn builders.

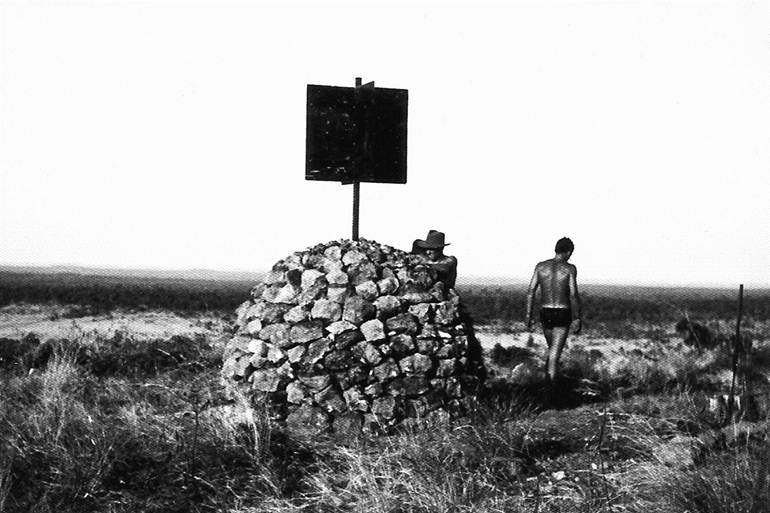

Figure 3: First cairn built by National Mapping at Moorkaie triangulation station, near Broken Hill, March 1954 - H.A. (Bill) Johnson is second from the left and E.J. (Ted) Caspers is on the far right.

Figure 3 shows the first cairn built by National Mapping and Figures 5 to 8 inclusive show 4 stages in the building of a cairn using the improved methods outlined below. This sequence of photographs, taken in 1964 at Caskey traverse station (NM\B\165) in Queensland, appears to he the only set which illustrates the art of cairn building. Plans of the steel beacon shown are held in the Technical Services Branch, Dandenong ‑ Plan No. 92SA (possibly in the National Archives now – Ed.).

Figure 4: Makeshift observing screen used on the Broken Hill - Carrieton triangulation

Three reference marks were emplaced. When the station was occupied they were to be referenced by angle and distance to a nail set centrally in the top of the pole, one R.M. thus becoming the “eccentric station” from which all observations were taken. This cairn building and reference mark procedure was used on this survey but improvements were made on subsequent surveys.

The main improvements were:

(i) Wooden struts were used inside the cairn to counteract the influence of wind on the vanes which was found to be causing some poles to gradually develop a lean. The struts solved this problem and also made for easier cairn erection as the pole was positioned and the struts were immediately attached once two layers of base rocks were in place. This allowed building to proceed at an even, steady pace; it also freed for building work the two persons normally required to hold the pole steady for such a long period.

(ii) Nails were set centrally in the side of the pole within the shelter of the vanes, one close to the top and one close to the bottom of the vanes. If the same length of each nail is left protruding, when a plumbob is suspended from the top nail and the pole moved until the point of the plumbob is directly over the same point on the bottom nail, the pole is vertical. Thus the “plumb” of the beacon can be checked at all times during the building, the wind having little influence on the sheltered plumbob string. Years later when steel poles came into use a good quality carpenter’s spirit level was used for this purpose.

(iii) With reference marks, angles and measurements were taken before the cairn was erected.

Figure 5: Cairn building step one – pole erect and “strutted”, collecting rocks.

Figure 6: Cairn building step two – setting in base rocks using measuring stick to keep symmetry.

Figure 7: Cairn building step three - cairn about two-thirds complete; symmetry is being maintained by measuring stick.

Figure 8: Complete cairn

On the Broken Hill triangulation cairns were now erected on all stations north of the line Mt Robe - Moorkaie (inclusive), eight in all. As the observing was to be to the beacon vanes in daylight, observing screens were a necessity; these were devised by making a tepee type frame from two inverted “V” frames of 3in x 2in Oregon. This was covered with the strip calico which had been salvaged after the aerial photography of the station marks had been completed. The resulting screen was very effective if slow and difficult to erect; it was probably the most important improvement in our observing technique to this date.

Observing now proceeded apace; evening, night and dawn observations being employed. The sights in that dry atmosphere in the evening were very good, those at dawn from very good to very poor. On a hot sunny morning the beacons disappeared almost as soon as the sun rose, however when there was a reasonable amount of cloud in the east the sights were good for a worthwhile period of time.

During this time there was one unfortunate happening. One of the field assistants returned to Broken Hill in a Morris 4 x 4 to collect petrol and supplies. He was involved in an accident in the city, tipping the vehicle over while avoiding some pedestrians. Apparently the whole accident was caused by a motor cyclist who took off at high speed and was not caught. The police were full of praise for our driver’s capability in avoiding the pedestrians but the upshot was that he received concussion and spent a week in hospital; the vehicle was badly damaged and had to be sent by train to Adelaide for repairs, thus diminishing our already small fleet of vehicles.

On completion of the observing, the field party returned to Broken Hill to compute eccentric corrections and finalise the triangle closures. It took tome little time to adopt a suitable field book layout both for the booking of the extra observations required and for the eccentric computations; plain unruled field books were at that time the only type available.

Final triangle closures were fair; the average was just about one second with no large misclosures. It was now well into March.

Broken Hill - Carrieton Triangulation

It was now decided that instead of measuring the longer base line the party would press ahead to make a connection to the Army primary triangulation near Carrieton, SA. This would enable preliminary coordinates on the Sydney datum to be calculated immediately for the stations in the Broken Hill area, and allow mapping to proceed. The measuring of the base on either side of a triangle near Broken Hill would be left to the Geodimeter.

Eight hills were beaconed in quick time although some delay was caused by the rear differential of one of the Morris 4 x 4 trucks breaking up. The eleven hills necessary to be observed were completed fairly quickly, once again observations being to beacons in the evenings and at dawn with some observations on the long lines to lights after dark. In addition heliographs were used for the first time and showed that they too could play an important role. The observing screens again proved a boon but their makeshift nature created an enormous mount of work in carrying them up steep hills and securing the long lengths of narrow calico to the frames as well as possible, the strong winds on the hills playing havoc with any loose section.

During this period the Senior Surveyor had one observer experimenting with a “double pointing” technique. In observing, the slowest operation is the locating of the distant target, therefore if while he has it in view, he takes two distinctly different pointings, reading the micrometer for each the observer achieves the value of two single pointing sets for very little extra time. This system is particularly suitable for the Wild T3 theodolite as the micrometer drum has either to be read twice, (or once and the reading doubled). The theodolite drill is to swing the instrument to bring the target close to the vertical hairs, clamp and then with the slow motion spindle, centralise the target between the twin vertical hairs, making the last action of the spindle “screwing in”, i.e., clockwise against the spring, then read the micrometer drum. Leave the instrument clamped, move the target just clear of the vertical hairs with the slow motion spindle, again centralise the target using the same drill as previously mentioned and again read the micrometer drum.

Another experiment at about this time was to break up the circle readings to 60º segments instead of 45º, thus making six arc sets instead of eight. These methods were soon adopted, and to help the booker, the sets were reduced as “arcs” instead of “rounds” to save a lot of mental arithmetic on his part.

A new Surveyor Grade 1, C.K. Waller, bringing a replacement Morris 4 x 4 joined the party for the final phase of this task. In 1954 April was a rather wet and windy month in the Broken Hill area; besides having boggy roads to contend with, one beacon (Felspar) was blown well off plumb. As observing into that station had been completed, the lean had to be measured for eccentricity calculations, the pole re-plumbed and the cairn re-built. This incident made us think of methods to stabilise the pole to counteract the influence of wind on the large surface area of the vanes, and as mentioned all beacon poles were “strutted” inside the cairn from about mid 1955.

Some small amount of re-observing was necessary to check in the Alindee area which had been done in poor visibility caused by dust storms preceding rain. When this was completed, results on this scheme were good, with the average triangular misclosure being under one second.

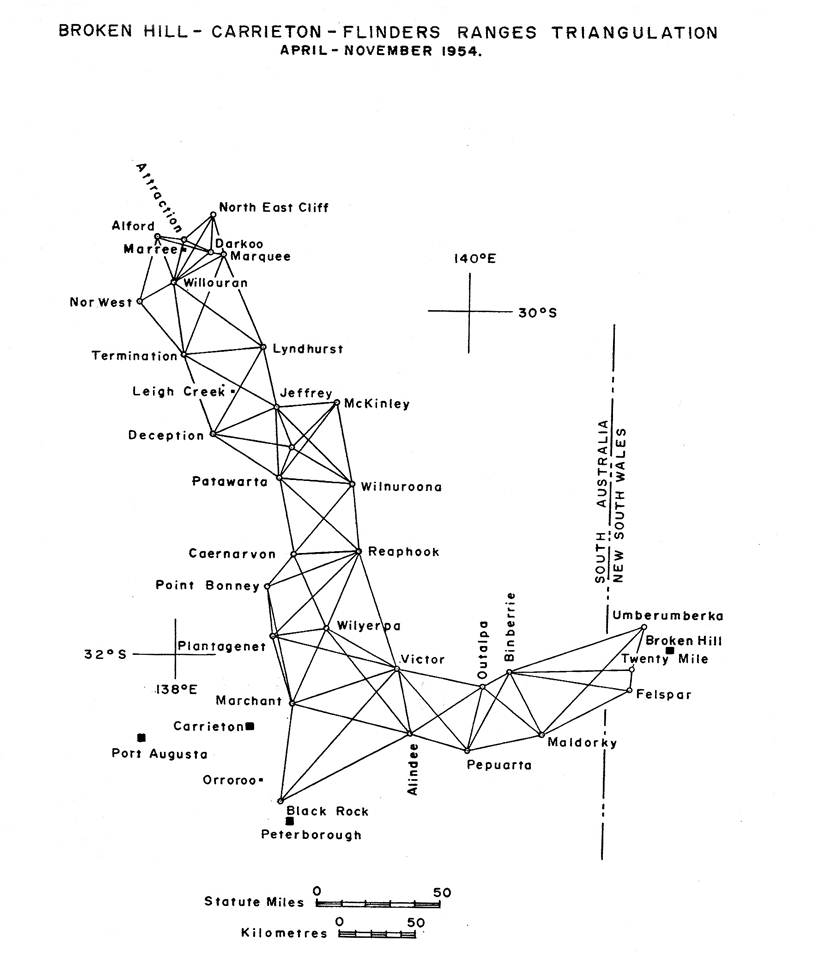

The work was now closed down at Broken Hill and surplus beaconing material taken to a hired store at Carrieton for the next phase. The field party returned to Melbourne while the Senior Surveyor with one observer to assist, proceeded to reconnoitre a triangulation chain northward from the line Marchant - Victor, through the Flinders Ranges to the vicinity of Marree, SA Figure 12 shows triangulation diagram Broken Hill - Marree.

Field Party, Broken Hill - Gap and Broken Hill - Carrieton, 1954

B.P. Lambert |

Director (Broken Hill reconnaissance) |

H.A. Johnson |

Senior Surveyor |

E.J. Caspers |

Field Assistant (Survey) |

R.A. Ford |

Field Assistant (Survey) |

W.J. Dingeldei |

Field Assistant (Survey) |

N.K. Hawker |

Field Assistant |

“Bluey” Wells |

Field Assistant |

J.H. Werner |

Field Assistant |

C.K. Waller |

Surveyor Grade 1 (short period only) |

Carrieton - Marree Triangulation 1954

Before the Broken Hill - Carrieton field work was finished it was decided the next task would be to push the triangulation chain northward from the line Marchant - Victor through the Flinders Ranges covering as much ground as possible before the year ended.

Old South Australian Lands Department triangulation diagrams were carefully examined. Their early surveyors had completed an enormous amount of work in the area, but to our surprise the lines were all short. Did this mean that the peaks were all even heighted and a large number of stations would need to be occupied?

The Senior Surveyor decided to hire a light plane to examine the terrain from the air. Two of the observers R.A. Ford and W.J. Dingeldei also went on the reconnaissance; an Auster four seater single‑engined aircraft was used. Cloud covered the ranges near Marchant and Victor but the sky cleared as the higher ranges near Hawker came into view. The Flinders Ranges are spectacular from the air, and it was immediately obvious that a very satisfactory chain with plenty of long lines could be selected by using the more prominent peaks. Numerous high rock cairns were seen. It was also obvious that there would be plenty of strenuous mountain climbing while on this scheme; luckily those on the plane were not adverse to this activity. The plane had to land at Marree to refuel and a quick lunch was taken from sandwiches brought along.

From Marree, as expected the low area with comparatively few hills as the survey chain would have to turn west to pass around Lake Eyre South, was to be the most difficult to reconnoitre from the air. However by flying low more high points were seen than had been expected and it was almost certain a satisfactory primary triangulation scheme was feasible. In the time available it was not possible to fly each line to prove line of sight. Once around the southern end of the lake it could be seen that the area to the north was good triangulation country. Unfortunately heading almost directly into the sun for most of the afternoon observing conditions deteriorated as the day wore on and all were glad when Oodnadatta airstrip came into view.

Flying southward next day with the sun generally behind the plane, visibility was much improved so checks could be made of those areas not properly sighted on the previous day. On approaching the north end of the Flinders Ranges, the rather heavily laden old plane made heavy weather of gaining enough height and a second approach had to he made to get sufficient clearance.

Broken Hill was reached in mid-afternoon; all involved in this flight realised how useful an aircraft could be on triangulation reconnaissance. This was the first time National Mapping had used an aircraft for this purpose.

Early in May the survey party returned to Melbourne while the Senior Surveyor proceeded to the Flinders Ranges and selected the triangulation stations, compiling detailed access sketches in the process. Preparations in Melbourne included the purchase of beaconing material, the manufacture of observing screen frames, and the designing and purchase of duck observing screens to fit the frames. The “tepee” type screen frame was designed and made from dural tubing by the Chief Topographic Surveyor who had a very good workshop at home. While the prototype frame was not stable enough on windy hills, modification in the field soon turned it into a very useful adjunct which was little changed when the Geodetic Branch finally closed down in Melbourne at the end of 1969. The screens themselves were of heavy duck and in two pieces; sides which came about chin high, and a top section which contained numerous overlapping panels to enable only a mall peephole to be opened to sight any particular station. Tapes were attached to tie these panels down. However they were not particularly successful and were replaced by larger strong safety pins which proved ideal. Zips were not used; they were very expensive at that time and there was a very real possibility that sand would immediately make them unserviceable. There was a hessian reinforced section of duck around the base of the screen upon which were piled plenty of heavy rocks to keep the screen from blowing over. During heavy winds at least one “guy” was attached to the top point of the “tepee”. Figure 9 shows an observing screen and cairn, Flinders Ranges triangulation.

Figure 9: Typical observing setup during the Flinders Ranges triangulation.

For beaconing, 4in x 4in dressed oregon poles were adopted and aluminium vanes were tried. They did not prove successful and marine grade bondwood vanes were adopted as standard while timber was used for beacons.

At this time the Geodimeter arrived, the Chief Topographic Surveyor and Surveyor Grade 1, C.K. Waller, commenced evaluation tests in the Melbourne area. The main equipment was in one large box weighing about 200 lbs, thus a “drive on” or a point with very short climb would be necessary for one end of any line measured, however the mirror for the distant end was a reasonable load for carrying up any hill. The principles of the Geodimeter are well known and therefore will not be elaborated upon.

If more information is required see “Introduction to the Geodimeter” by G.R.L. Rimington, M.I.S.Aust, MAIC, in “Cartography” Volume l, No. 3, March 1956, the Journal of the Australian Institute of Cartographers. Suffice to say here that the best measuring distances were 5 to 9 miles, up to 15 miles could normally be measured and once only a measurement of 19 miles was made.

On the completion of his reconnaissance of the Flinders Ranges, the Senior Surveyor returned to Melbourne to recruit field staff for that phase of the work. One of the observers, E.J. Caspers was to return to survey computation work in the office, C.K. Waller and a field assistant plus a new Grade 1 Surveyor would form the Geodimeter party which would mostly work independently. Two field assistants resigned,

The resignation of field staff after one or two seasons became a regular feature of all National Mapping field parties during these years of full employment. Married men were prevailed upon to get another job which would keep them home, adventurous young, single men wanted to move on after a couple of trips, or alternatively got married and decided to seek a 9 am to 5 pm job. Needless to say this did not make the party leader's or the experienced observer's job easy; they were constantly teaching both new bookers and new observers their technical tasks, as well as cross-country driving and the art of living in the bush.

The triangulation party was ready for the field again early in July and returned to the Carrieton area. Only two observers, R.A. Ford and W.J. Dingeldei, were available, but it was expected the two surveyors’ grade 1 from the Geodimeter party would be in the area in time to give some assistance with the observing. Three short wheel base Land Rovers with trailers and two Morris 4x4 trucks were available.

On arrival in Carrieton two beaconing parties, one of four and the other of five persons were organised. The plan was to beacon the hills from south to north to the Marree area, then commence observing, working from north to south.

The beaconing was a strenuous time as most of the hills were a two hour climb and a couple were of three hours. Take four hours climbing time out of a winters day and there is not much time to spend on the summit where the old cairn had to be dismantled, the pole and vanes set in, the cairn re-built and the necessary clearing done.

“Yukon” packs were used to carry the vanes, nails, fencing wire, cement, water, axes and lunch, etc., the twelve foot pole and crowbars were shoulder loads. The cairns on the prominent peaks were magnificent; about seven feet high and still in good condition though over eighty years old; as little as possible of the outer wall was disturbed, the loose centre rock fill was removed, the pole set centrally and then the cairn was re-built. A cross in a circle cut in rock was the usual old station mark; a hole was made in the centre of this with a star drill and either a very short length of half-inch diameter copper tube or a silver sixpence was set in the hole as National Mapping’s station mark. Luckily little clearing was required, mostly a few bushes only on these high peaks.

Descending the mountain was the most pleasant part of these beaconing trips; one could look around and admire the magnificent scenery. Visibility was at its best in the late afternoon and this could be contemplated with the satisfied feeling of a day well spent, a good hot meal ahead and a pleasant evening around the camp fire. At that time a leading popular song was “The Happy Wanderer”, a Swiss mountaineering type – it was immediately adopted as the survey party's theme song.

Mt Caernarvon when viewed from the Blinman road presents a precipitous western slope and would probably be a solid two hour climb. However, if approached from the east it was considered that a four wheel drive vehicle could reach the summit via a torturous route through the lower gullies.

The party managed this and the beaconing was completed; however the dreaded happened in one of the gullies - the rear differential of the Morris gave up. A long steel cable complete with block and tackle was borrowed from a small mine in the vicinity, and by anchoring the block and tackle to a tree on the summit of a crest, using front wheel drive of the Morris, while the Land Rover with the end of the cable attached drove downhill thus hauling the heavier vehicle up the very steep pinch. This was repeated three or four times before the Morris was clear of the gullies. It was a great relief when the vehicle was again on a road.

One further hill, Mt Deception, was completed en route Leigh Creek to order spare parts for the Morris. It was a most miserable morning, a Saturday actually, when the party headed for Leigh Creek. The wind was strong and bitterly cold with the visibility down to a few hundred yards owing to the thick dust clouds stirred up by the wind. Just outside the town some vehicles emerged from the gloom; it was the other beaconing party which should have been nowhere in the vicinity. It didn’t take long to find out the reason, they too had a broken down rear differential on their Morris. This meant hurried extra telegrams to Melbourne to ensure it was understood two sets of spares were required. From memory once this lot of repairs was made no further trouble with Morris rear differentials was experienced; I think some modification was made, the vehicles were used for another couple of years and generally gave good service during that time.

On completion of the beaconing both parties assembled near Marree to prepare for the observing. Bookers were trained and the observing screens tried out. It was immediately apparent that in actual operation they needed a horizontal bar about chin high, both to stiffen the frame and upon which to lace the lower half of the screen. Some canes were obtained from the centre stems of local date palm fronds and these served admirably on this survey after which they were retired and replaced by dural tubes. The two observing parties then commenced observing on the hills in the vicinity of Marree, some heliographs being used on difficult lines.

Figure 10: Setting in observing pegs on Darkoo Sandridge near Marree SA.

Near Marree, the observers had their first experience of observing from a sandridge. At Darkoo, long pegs were inserted as stand points for the theodolite tripod. Figure 10 shows the setup being prepared. From this time on, oregon pegs 3 inch X 3 inch x 36 inches were always carried for use on sandridges.

While this observing was in progress the Geodimeter party arrived and attempted to measure the line Attraction - Mt Alford but were prevented by the sudden large shifts of the light beam caused by refraction. The two surveyors, C.K. Waller and T.M. Austin, then formed an observing party thus making three such parties available for the higher peaks to the south.

Constant dust storms in the area between Lyndhurst and Marree caused the observers much anguish. It was a drought year; also the Commonwealth Railways were constructing their standard gauge line north from Port Augusta to serve the Leigh Creek coalfield, and later Marree. Their earth moving equipment and quarrying operations meant almost daily dust haze. From Lyndhurst south, the main ranges with their high peaks were not too badly effected. Observing took from late August until early November; twenty-two hills were occupied in all. Camping on the peaks was necessary at Wilyerpa, Point Bonney, Patawarta, Mt Hack, Mt McKinley and Mt Termination; it was possible by moving at speed to get back to the vehicle soon after dark from the other summits.

During this time a couple of the new field assistants resigned just when they were most needed on the steep climbs. This was the first time that anyone from the triangulation parties had resigned in the field. In this case the reason was quite obvious, the two who left were neither physically nor mentally tough enough for our type of work.

Visibility was good from the high peaks, even so, final triangle misclosures indicated some cheek observing was required, some on the high peaks and some on the low hills near Marree where dust storms had caused trouble on the longer lines.

A least squares adjustment was done on the figure which involved the high peaks; this indicated the errors were fairly evenly distributed at Mt Patawarta, Mt Reaphook and Mt Caernarvon, the first two having been observed by an experienced observer while the last was observed by an inexperienced observer. Check observing did not change the result at Patawarta or Reaphook but large differences were found at Caernarvon, the new results giving good triangular closures. Which goes to show the least squares adjustment gives a “most probable” solution; however, it is noticeable if there is a large error at one point there is a tendency to distribute this error to the other points. No firm reason could be found for the poor original results, the general opinion being that the tripod had been on an insecure footing.

Further observations were attempted in the Marree area; once again the dust storms were at their worst, only the closer stations being visible through the constant dust haze. Some improvement to the triangle misclosures was made but under the conditions it was not economical to keep the survey party in the area any longer and all returned to Melbourne during November.

Vertical Angles

During this type of observing (high peaks without radio communication) it was not possible to continue with simultaneous reciprocal vertical angles; from this time onwards observations were done at about 1400 hours (actually two hours after the sun was on the meridian, local time). At approximately this time it can normally be expected that the air would be most evenly heated and vertical refraction inconsistencies at their minimum.

At 1400 hours each observer would as quickly as possible observe all distant stations, laying on the top of the vanes where possible, or to the top of the hills on the longer lines where the vanes could not be sighted at this time of the day. In this way some almost simultaneous reciprocal vertical angles were observed. The double pointing system was also used; each time the top of the vanes was sighted the bubble was also moved off and re-adjusted prior to reading the micrometer drum. When computing, all results were examined and greatest weight given to the shortest lines where the vanes were sighted.

Communications

Owing to the small observing parties and the long climbs involved, the VHF radios could not be used on this scheme, the weight of the twelve volt battery being the main barrier to their use.

The old AWA 3BZ short wave transceivers were new falling to pieces; the constant travelling on corrugated roads taking their toll of a set which was not designed for mobile use. These sets were of little use for inter party communication as National Mapping had no frequency allotted, this making it necessary to rely on the good grace of the Flying Doctor Service Base operators and their outstations for time to make a call before the telegram sessions started. Consequently they were becoming too difficult and time consuming to use and telegraphic contact with Melbourne was more satisfactorily maintained by telegram to and from the nearest Post Office.

Geodimeter Type NASM-1

Upon receipt of the equipment in May 1954, the Chief Topographic Surveyor and Surveyor Grade 1, C.K. Waller, conducted familiarization tests near Melbourne to find suitable operating procedures and to obtain a working knowledge of a piece of equipment entirely new to the surveying profession.

It was found that a strong steel table upon which to mount the 200lb Geodimeter would have to be designed. It would need to be triangular in shape and the top would need to have the capability of being roughly levelled when the table was set on uneven ground. A 12 feet by 12 feet Auto tent would be required as shelter and a vehicle with a long wheel base capable of providing a reasonably gentle ride over corrugated roads was required for transport. An orthodox two wheel drive international panel van was selected as the most likely vehicle to fulfil this purpose.

In August 1954, the party proceeded to the Carrieton Army Base Line and measured that four mile line without trouble. Whilst in that area the nineteen mile triangle side Maurice Hill - Black Rock was measured with considerable difficulty; the bright moonlight and the long line both causing trouble. The next measurement was the side of a triangle in the Broken Hill triangulation scheme, the eight and a half mile line Felspar - Twenty Mile, near the border village of Cockburn. Figure 11 shows the Geodimeter set up for a measurement.

A move was now made to Marree, South Australia, and an attempt to measure the twelve mile line Attraction Hill - Mt Alford was made. However bad atmospheric conditions caused large vertical jumps in the return light beam, making it impossible to keep the light on the receiving mirror long enough to obtain a result.

The Geodimeter was now put aside while assistance was given with the theodolite observing on the Flinders Ranges triangulation.

A further measurement of the Carrieton Base was made in November before the party returned to Melbourne. After necessary maintenance the Geodimeter was taken to Benambra in Victoria and the six mile long Army baseline was measured in December.

For those interested in more detail, the article “Field Use of the Geodimeter” by C.K. Waller, B.Surv., MAIC, published in “Cartography”, Volume 1, No. 3, March 1956, provides full details of the pioneering days of this equipment, 1954 and 1955.

The following tabulated results are from that article:

Date |

Place |

Line Measured |

No. of pairs of Readings F1+F2 2 |

Approx length (Miles) |

Probable Error (± feet) |

Geod. minus Survey (feet) (V =299,792.5 km/sec.) |

|

Aug 54 |

Carrieton, SA |

Geod. base line |

4 |

4 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

|

Aug 54 |

Carrieton, SA |

Triangle side, Maurice - Black Rock |

4 |

19 |

0.04 |

- 0.01 |

|

Nov 54 |

Carrieton, SA |

Geod. base line |

4 |

4 |

0.01 |

- 0.01 |

|

Dec 54 |

Benambra, Vic |

Geod. base line |

6 |

6 |

0.01 |

+ 0.01 |

|

Figure 11: Measuring with Geodimeter Type NASM-1 - typical setup with C.K. Waller at the control panel.

Summary

It had been an amazing year; forty one First Order stations had been observed and the triangulation chain from the north of the Barrier Range near Broken Hill to the Marree area covered a distance of 460 miles. Who would have thought when we started laboriously observing single triangles around Broken Hill in January that before the year was out, we, with a very small survey party, would have completed a primary triangulation chain from there to Carrieton in South Australia and then north through the mighty Flinders Ranges to the shores of Lake Eyre? Also we could now see clearly the way ahead; the chain would be continued north across the continent to Darwin, sufficient hills in the flat areas permitting. With the Geodimeter available to measure the side of a triangle every 250 miles or so there would be no need for tedious base line measurements, or the observing of time consuming base net triangulation schemes.

Field Party Carrieton - Marree (Flinders Ranges) 1954

H.A. Johnson |

Senior Surveyor |

R.A. Ford |

Field Assistant (Survey) |

W.J. Dingeldei |

Field Assistant (Survey) |

V. Bouchard |

Field Assistant |

K. Fevarvi |

Field Assistant |

G. Jaeger |

Field Assistant |

E. Sachs |

Field Assistant |

E. Stuart |

Field Assistant |

P. Svoboda |

Field Assistant |

Geodimeter Party

C.K. Waller |

Surveyor Grade 1 |

T.M. Austin |

Surveyor Grade 1 |

N. Hawker |

Field Assistant |

Figure 12: Triangulation diagram Broken Hill - Marree.