Recollections………

Recollections………

1370th Photo Mapping Wing Team at Mt Scott – Station 25

Prince of Wales Island, Torres Strait

1963 & 1964

Bill Snell, Indian Rocks Beach, Florida

(Mr William (Bill) Snell was a former Airmen First Class in the United States Air Force (USAF). During the period 1963-1964, Bill was assigned to Aerial Survey Team (AST) - 7 of the USAF’s 1370th Photo Mapping Wing, tasked with project AF 60-13 aka the Southwest Pacific Survey . The aim of that survey was to establish the principal islands of the Southwest Pacific area on a common geodetic datum including connecting New Guinea and the adjacent islands to the geodetic network on the mainland of Australia. The project was accomplished by aerial electronic survey, specifically HIRAN. One of the sites occupied during this survey was Mt Scott (Station 25) the highest point on Prince of Wales Island (adjacent to Thursday Island in the Torres Strait). While the official reports are factual Bill’s personal recollections give a more detailed insight into one site of that survey.)

The following pictures were taken on Prince of Wales (POW) and Thursday Island (TI) in the Torres Strait while I was serving in the USAF 1370th Photo Mapping Wing as a crew member on HIRAN Ground Station #25. Airman Gayle Wyman and Airman Robert West, both HIRAN operators, and I made up the crew. I was responsible for Ground Power.

|

|

|

|

Section of R502 series map at 1:250,000 scale showing location of Mt Scott on Prince of Wales Island in relation to Thursday Island and Cape York at the tip of mainland Australia. |

|

|

|

|

|

From Mt Scott north towards Thursday Island at centre-back of photo. |

From Mt Scott south-east towards Cape York over Entrance island. |

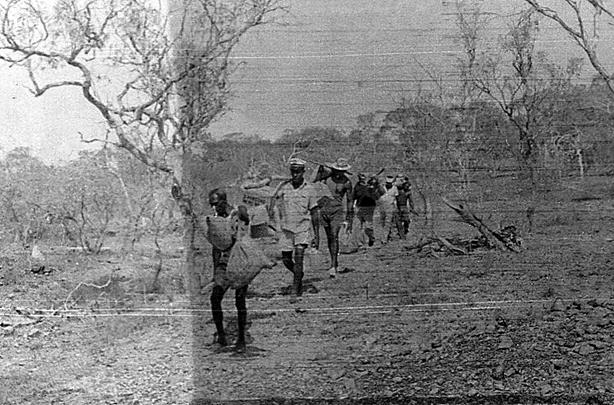

We arrived on Horn Island early in the morning of November 23, 1963 flying in a Douglas C-54 Skymaster from Port Moresby. A crew of 30 Islanders unloaded the equipment, loaded it on boats for the short trip over to POW. Once the boats were unloaded we set off immediately for the walk up to the site on Mt Scott taking only living essentials and leaving the station equipment on the beach.

|

|

|

|

Leaving the beach. |

Approaching the foothills. |

We had

no map and no instructions other than “the Islanders know the way, look out

for snakes and no one lives on the island”. We walked along the beach for a

short way then turned into the bush. At first the walk was easy but once into

the bush at the base of the foothills it became an arduous effort. It seemed

like anything that grew had huge thorns that would rip through clothing, or was

so dry and tough it seemed impossible to chop through. There was no trail of

any kind and the ground was very rocky making it difficult to keep ones

footing. The undergrowth was exceptionally thick often covered with vines almost

impossible to cut. I remember thinking how would the Islanders ever carry our

heavy gear, fuel, water, etc. through this stuff? Having already spent some time

working with native carriers in Papua New Guinea (PNG) I remembered how often

they could do what seemed impossible so put that thought out of my mind for the

moment.

|

|

|

|

Airmen Wyman leading the way up the first mountain. |

Airman Wyman bringing up the rear in the flat lands. |

The distance from the beach to the top of Mt Scott was around four miles and took us about four hours. Once on the top of Mt Scott we found the survey marker quickly, decided how we wanted to lay out the site, and work started immediately to clear the area of brush. A recon team had selected the site and emplaced the survey mark well in advance of ground station operations. The survey mark was about 3” in diameter. Made of brass it had a pin underneath that was embedded in rock and/or concrete. After installation the mark was embossed with the direction of true north. The HIRAN antenna was installed over the mark using a plumb line from the center of the antenna to the mark and precise positioning by adjustment of the antenna guide wires.

|

|

|

|

|

Almost at the top of Mt Scott. |

Survey marker. |

HIRAN aerial. |

Shortly after arriving, for some reason I can’t remember why after all these years, one of us had to go back to the beach for some essential. I felt confident I could find the way back so made the trek to the beach to collect the item.

After leaving the beach for the return walk I heard a lot of noise behind me and soon an Islander appeared running towards me shouting “President Kennedy shoot himself, President Kennedy shoot himself”. The two of us stood there in the bush and he repeated this again and then without another word turned and ran towards the beach and I never saw him again. Later we learned that Kitson Thorpe from Thursday Island, whose family ran the transport company that took us from Horn Island, had sent him to tell us the news. To this day it was an unforgettable moment.

The living and operations areas were cleared of brush that first day. We were amazed at the amount of work the Islanders accomplished. They worked without breaks until dusk then built a huge fire and all sat around it, eating and talking well into the night.

|

|

|

|

Work starts clearing brush and (lots of) rocks on Mt Scott. |

Captain (wearing white hat in background) and his team taking a break – Bill (far left foreground) and John Lo Wata. |

We had left our tents on the beach and planned to sleep on cots out in the open. It was dry season and we were not concerned about rain.

Sometime in the middle of the night I woke up and found all the Islanders still sitting around the fire. They had brought mats with them to sleep on but only one of them was sleeping. The man sleeping was the one in the picture above, behind me. His name was John Lo Wata. Also note in the picture above the man in the white hat, he was the Islander leader, spoke little English and was called “Captain”.

Also note the rocks! It became obvious to us that clearing just the brush would not result in a safe, workable site. The helicopter pad and paths around the living, operations and power unit areas would have to be cleared of rocks; a lot of rocks!

|

|

|

|

Our camp on the first morning after arriving on Mt Scott. |

|

At day break I woke up to find the Islanders still sitting around their fire talking. Captain came over to me indicating the men were very tired as none of them had slept, also that four men had left during the night. Nonetheless he started them working and they worked until dusk stopping only briefly for lunch. We worked too, but they out-worked us two or three to one.

Again on the second night John Lo Wata was the only one who slept, the rest sat around the fire all night. When dawn arrived we found Captain was gone along with five or six other Islanders.

John announced he was now the team leader. Why did the men leave? A long difficult conversation ensued that seemed to indicate the men left because they could not sleep. Why? All we could understand was the men were afraid, but of what? John said the reason was ghosts; the island was haunted and they were too afraid to sleep.

After the discussion work started and they worked just as hard as before. However over the next three nights we woke up to find more of the crew gone until only John remained.

As this unfolded we faced a serious predicament as the expectation was we would be mission ready in less than a week’s time. Back on the beach we set up a power unit and radio and informed AST-7 HQ that we were going to require a helicopter. The reaction was as expected but after a lot of discussion we were told to clear a pad on the beach, complete the pad on Mt Scott and be ready for the ship and helicopter in about a week.

While waiting for the ship John and the three of us worked from dawn to dusk finishing the clearing. In the evenings John told us the history of the area. Barbara Thompson, the lone survivor of the 1842 wreck of the America, struggled ashore at Prince of Wales Island where the local chief, Borota, took her into his care and she began a life with the natives. Five years later, a naked woman ran to sailors landing from HMS Rattlesnake and told them in halting English her amazing story. Barbara Thompson was only 21 when she arrived back in Sydney (the most accurate account of her story is contained in “Islanders and Aborigines at Cape York” by David R. Moore. Moore used actual interviews of Thompson by O.W. Brierly a crew member and artist on the Rattlesnake). There was the massacre by the Jardine brothers, Frank and Alick, who at 22 and 20 took a mob of cattle overland for the supply of the newly established settlement at Somerset (10km SW of Cape York), where their father was Government resident. Attacked by natives several times during their journey they killed many defending themselves. Then after the 1869 massacre of Captain Gascoigne and the Malay crew of his cutter by the natives of Prince of Wales Island, who also carried off the Captain' wife and son, the culprits were executed and the islanders relocated to Horn Island (more can be found here ). John said that this massacre was the reason the Islander crew left us; the island was haunted by the ghosts of those people and the Islanders were simply too terrified at night to sleep for fear of the ghosts. We were never able to learn why John was unafraid in spite of many conversations. He had issues with magic too. He had lost an eye to a spell his sister-in-law had put on him; while spear fishing his spear had flown back and hit his eye.

The ship arrived. Our equipment and gear was lifted to the site and we started the installation immediately. We were up and mission ready within a day or two. The first week we ran missions every day.

We had adequate water stores for drinking but really limited amounts for washing clothes or ourselves. Soon this became unbearable. We discussed walking to the beach to wash but the thought of doing so in salt water along with the walk to and climb back did not seem appealing.

There were a number of animal trails that cut through Mt Scott. Some of these trails were almost like tunnels through the brush, following them required walking bent over in many places and some would allow walking almost upright. One morning I decided to explore a trail that led off the mountain to the northwest in hopes of finding fresh water. The trail was downhill most of the way and eventually opened into an area of rocky terrain that included what looked like a dry stream bed. I followed this and stumbled upon a pool of water maybe thirty or forty feed wide and in places three or four feet deep. What a find! This water was about a mile from our site. Once we cleared some difficult parts of the trail we could be there in less than 30 minutes. What a relief it was to be clean with clean clothes!

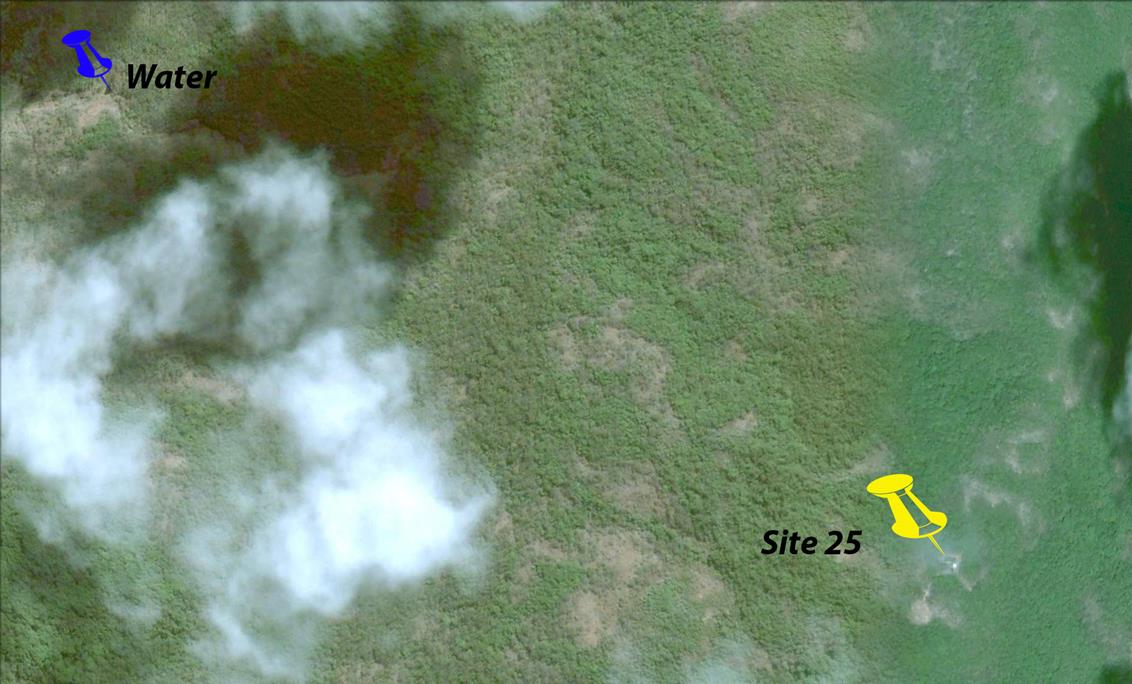

|

|

|

Area of Site 25 on Mt Scott and location of fresh water can be seen in this Google Earth image of 2009. |

One day without a mission, we were finishing up breakfast when a large white dog with black spots ran onto the site. Obviously friendly he bounced around each of us, tail wagging, checking us out and then running around the site. A few minutes later an old man came chopping his way through the dense brush onto the site. “Hello ole chaps, my name is Jimmy Joyce”, he said in a loud jovial voice.

It seemed someone did live on the island. Jimmy lived along a creek bed on the northwest side of the island. He must have been in his late 50s then, very thin but fit. He raised pigs and goats that he sold to people on Thursday Island. He had moved to POW having spent most of his life working on cattle stations. He turned out to be an enormous help to us, a major logistical resource, and a good friend.

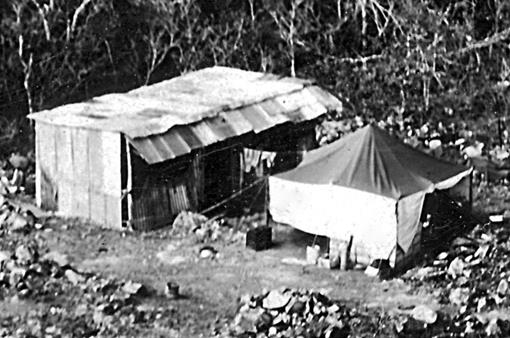

Once the greetings were exchanged he immediately told us there was no way we could survive up here in a tent. In a month or two he said for sure the area will be hit by a cyclone, as he waved his arm across the site, this will all be destroyed. I’ll build you a house because you won’t survive up here without it.

Nothing we could say would deter him and he started chopping down small trees for framing. When we offered to pay him his answer was simply “be my friend, and if we’re ever on Thursday Island together buy me a beer”.

|

|

|

|

|

Jimmy’s tin house and cook tent. |

Power tent and generators. |

HIRAN tent. |

Jimmy was right and in February we were hit by a major cyclone that destroyed everything, HIRAN, radios, power units, tents blown away. But that tin house withstood it all and we basically slept through most of the storm.

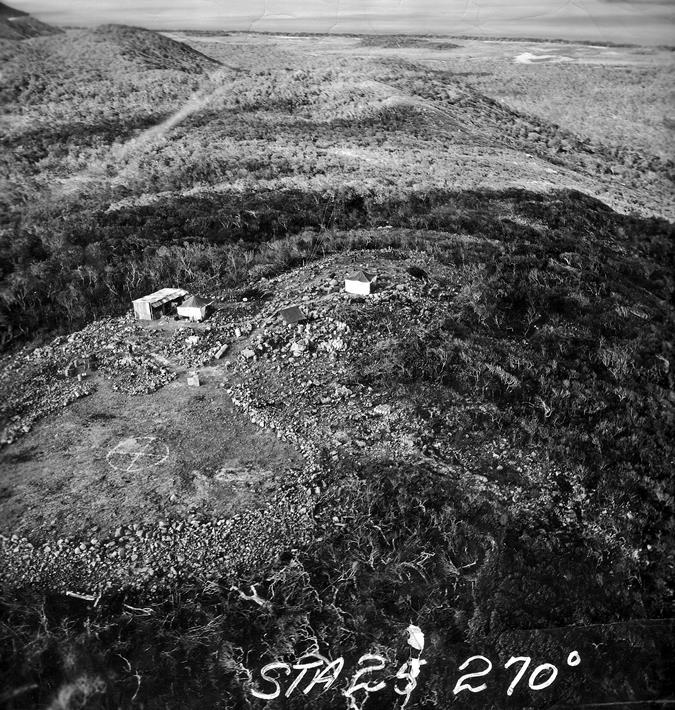

|

|

|

|

Site photo taken by USAF during project. |

View in Google Earth 2009 – top right shows same coastal flats. |

We were out of commission for over a week. Both power units had cracked oil pans and other irreparable damage, the radios and HIRAN were blown almost off the site. We started cleaning up and late that morning the Squadron C-54 from Port Moresby flew over us and dropped water and other supplies. I do not recall how we communicated our situation other than waving and gestures to the flight crew. Later we may have used a radio on Thursday Island (TI). Eventually the ship and helicopter arrived with new power units, radios, and HIRAN. During the down time we visited TI.

|

|

|

|

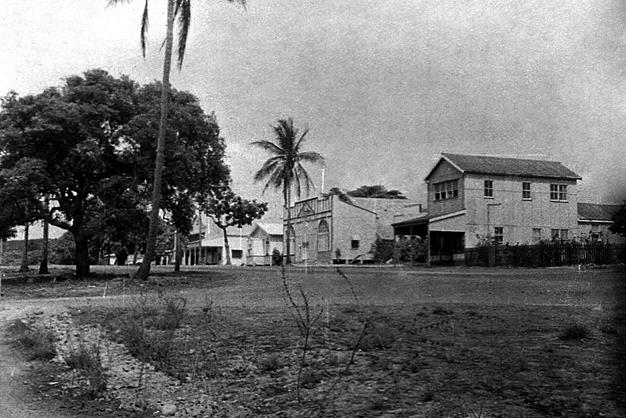

Main Street Thursday Island in 1964. |

Douglas Street TI. |

|

|

|

|

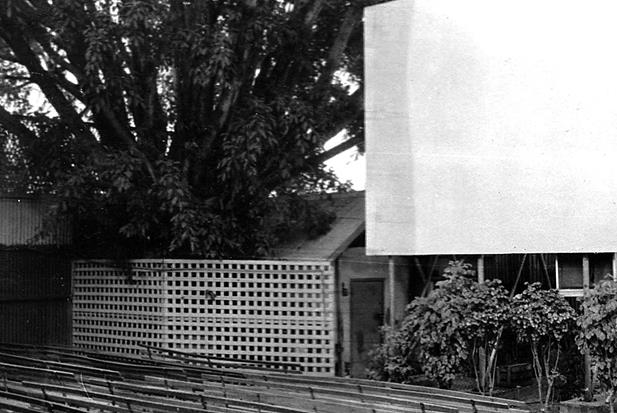

Outdoor Movie Theater TI |

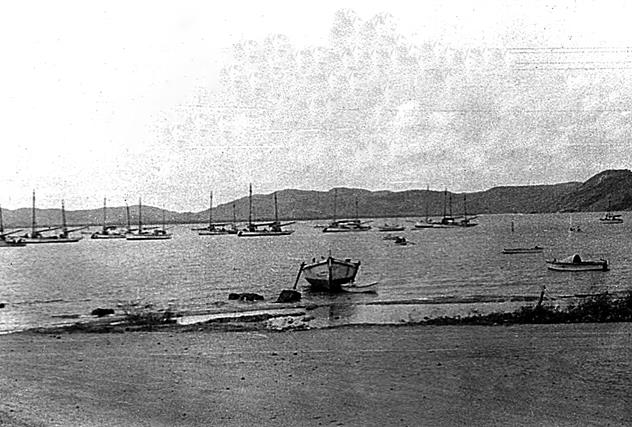

Last of the Pearling Luggers with Mt Scott at center-back of photo. |

|

|

|

|

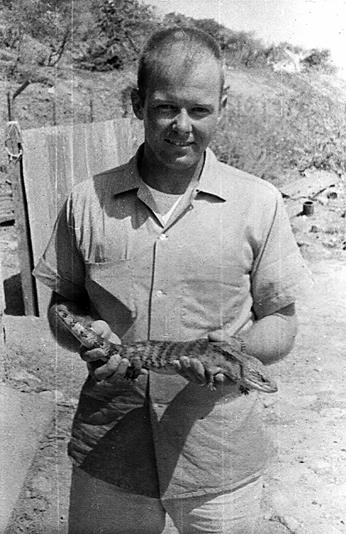

Robert West with critter on TI. |

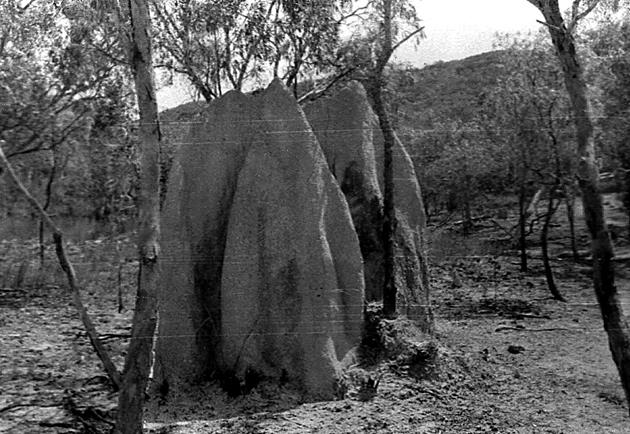

Anthill on Prince of Wales Island - common on low lands. |

One evening at check in with AST HQ we were told to meet an Australian survey team on the beach and lead them up to our site (As the Topographic Squadron of the Australian Army was in PNG in 1963 & 64 and “connected to a number of HIRAN stations” it is believed these men were part of that survey - Ed). I walked down to the beach at the appointed time to find three Army men in a small boat. They told me they were running lines with lights and needed our survey marker to run lines over to Cape York and an island near there. As they unloaded I noticed three large, heavy batteries. They loaded these on their backs along with other gear and off we went for the 2½ mile walk to the site.

They would not allow me to carry anything for them, not even a canteen. By the time we reached the base of the mountain I was exhausted keeping pace with them. We rested for a while and then completed the climb without another break. To this day I remain in awe of those three men caring those batteries up that mountain.

Memory fails regarding the time they were on site. Except, they told us they would work through the night and leave in the morning. When we awoke at dawn they were gone. This was the only evolvement we had with other survey people while we were in the Torres Strait.

It was an adventure and privilege of a lifetime to have been a part of surveying PNG and northern Queensland. I met wonderful people who were incredibly kind and helpful to our mission and to us personally.