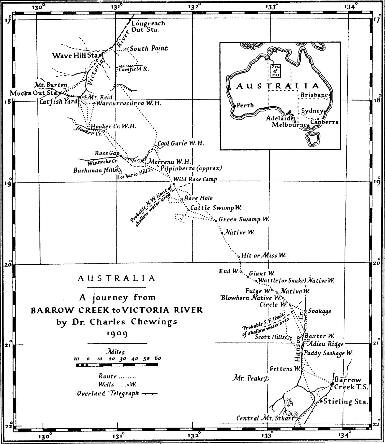

A Journey from Barrow Creek to Victoria River

Dr Charles Chewings

The Geographical Journal, Vol. 76, No. 4 (Oct., 1930), pp. 316-338

Published by The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers)

Early in January 1909 the writer made an agreement with the South Australian Government to open up a line of waters, for a stock route, from near Central Mount Stuart to the Victoria river, so that stock bred in the Victoria river district might be taken direct to Alice Springs instead of by the roundabout route to Newcastle Waters, and then down the Overland Telegraph Line. Mr. F. B. Wallis kindly lent twenty camels and gave financial assistance as well, while the South Australian Government agreed to pay for any trial wells made at reasonable distances apart that would yield a fair supply of good water.

On 8 February 1909 I left Adelaide with stores for six months, including a fair supply of dried beef, which proved a great success, though because it was heavily spiced the black boys objected to it and would only eat it minced fine as a hash, with dried vegetables. We bought fresh meat wherever possible, and also took in salted beef at the last station, Barrow Creek. My three companions, John Gettens, Harry Baxter, and Richard Douglas, joined me at Oodnadatta. They were all experienced bushmen, and used to mining and well-sinking. At Barrow Creek I secured two black boys, Tim and Paddy. Paddy knew the country to the west and north-west of Barrow Creek. The Hanson Creek country he knew well, and he had been as far west as the Lander Creek. For years past the rumour had been current - derived of course from the natives - that there were natural springs in the sandhills north-west of Barrow Creek. Paddy had visited some of these springs, and agreed to pilot me to them. They were far off, however, and the trouble was to find water low down along the course of the Hanson Creek, say 35 or 40 miles north-west of Barrow Creek, that would enable us to reach the first spring. From here, Paddy said, the distances between the springs were not very great.

With the help of these springs, if they existed, I hoped to be able to reach Winnecke Creek - so named by Alan Davidson on the journey when he discovered the Tanami goldfield. The creek was discovered by Nat Buchanan, a hardy old bushman, on his remarkable journey through quite unexplored country from Powell Creek to the Victoria river. Buchanan travelled with horses, and had only a black boy for companion. His route was north of mine, and must have been through the country where the ill-fated aviators, Anderson and Hitchcock, recently lost their lives. Buchanan, it is reported, had a very arduous trip, and only succeeded in getting through to Winnecke Creek by finding a native well or two. As no one has since visited the wells it is not known whether they are permanent or only contain water for a few months or weeks after the rainy season. Many of the natives' wells in the country he passed through are not permanent.

From Winnecke Creek I hoped to reach the great south-east bend of the Victoria river, near which is the Mucka outstation of the Wave Hill cattle station. The Catfish set of yards, which are quite close to the bend, and the water-hole bearing the same name, were my real objective.

The South Australian Government had supplied me with a light portable boring plant, and I had this so made and packed that we could cry a halt, boil the billy, and start boring for water in half an hour. We were able to carry 200 gallons of water in our casks, and when in dry country kept to the following programme : When leaving any water we had made or found, we filled every keg to the brim, kept the camels out from water until midday, when they would take a good drink, and then travelled until dark, when we tied the camels up all night and shepherded them until they ate their fill in the morning, and then travelled all day. If towards evening we were fortunate enough to find a spot that looked promising for water, we would camp, and while the boys watched the camels graze we drilled a hole as quickly as possible. If we failed to find a likely spot we tried again next day, and if unsuccessful, again the next, and so on until forced to return for water. If we found a site, and in due course water in the bore, it became a question whether we and the camels could hold out long enough to enable us to sink a well to the water. We might have saved many miles of travel and much time by taking with us a small pump and piping to lift water from the boreholes while sinking the wells.

We found that water was to be had in plenty in the hollows and titree swamps in the sandhill country, and at shallow depths. The swamps were all dry. They only hold water for a month or two after heavy rain. Occasionally we struck a salt bore, but more often good potable water was obtainable, and in quantity. Our greatest successes were obtained in open titree swamps that showed travertine limestone here and there. The so-called springs of the natives were almost invariably in spots of that description. Over quite extensive areas the permanent water-level appeared to be uniform, the sandstone in which the water lies being sufficiently porous to admit of adjustment to a common horizon. It is highly probable that much of the area over which we travelled was in past geological time a vast depression, into which much sediment was washed by flood waters. The channels of those ancient watercourses are now filled with sand, and the present-day flood-waters, soon after leaving the ranges, spread out over the country and are swallowed up in the ocean of sand. The vast depression - or series of depressions - is now nearly filled with wind-blown sand; and the surface consists of a wilderness of sandhills, sand plains, and titree swamps that are dry except for a short time after heavy rains. The porous surface absorbs every drop of rain water that falls, but the sand prevents rapid evaporation, and the water is conserved in the sand and sandstone below. How far one would have to sink through this sandstone to reach bedrock it is difficult to say; but in the centre of the sandhill area its thickness may he, and probably is, great. The quantity of water thus stored away is inexhaustible. Unfortunately the country is a dreary waste, in which food for stock is almost an unknown quantity, except after good rains, when succulent herbage such as parakylia, munyeroo, creepers, and similar fodder grow on the sandhills and plains. But the fierce heat of summer soon destroys it, leaving only an open forest of desert eucalyptus, stunted mallee, and corkwood, and in the north, thickets of turpentine bush in addition. The whole area is covered, and in places densely so, with spinifex, which is for the most part of a very poor quality, and useless for stock. It is a rank-growing variety, having much resin, with a smell resembling turpentine. The white ants (termites) make use of the resin for cementing material in the construction of their tunnels that run from bush to bush, and in the building of anthills - which, by the way, are a universal feature in the periodically inundated areas. In the clay flats, and more particularly where the flood waters run over the banks of creeks, as for instance on parts of Winnecke Creek, they are built so close together that it was difficult to get our string of camels through without bumping and disarranging the loads. Four, five, and six feet is their average height in such places. The bottom portions of the anthills, in horizontal section, are rarely round, but mostly oval or lense-shaped, and, as first noted by Mr. Alan Davidson, they are built on Gothic principles. The longer diameter of the section of all of them points in one direction. Their colour is deep chocolate-brown, and but for it they resemble headstones in a huge graveyard.

A peculiar and striking feature, most pleasing to the eye in that land of fearful monotony, are certain stretches of fine large and beautifully green gum trees. As a rule these run along by the sides of the largest sandhills, on sandy soil, there being nothing to indicate the presence of more moisture where they grow than elsewhere. Beside these gums grow stunted eucalyptus and corkwood. A particularly fine run of large gums occurs to the south of Green Swamp well. They are as handsome as the best salmon gums on the West Australian goldfields, and, like that variety, the leaves shine as though varnished, but the colour of the bark is light grey, not salmon pink.

From the time one leaves the neighbourhood of Hanson Creek until nearing Winnecke Creek, about 200 miles, there are no landmarks. To steer a direct course is a tedious business. The whole country being lightly timbered, no length of outlook is possible. It is only possible to get any sort of view at all by climbing trees, and from them one sees nothing but treetops and gentle undulations to the horizon in all directions. The monotony is appalling. Travel in any direction brings the same landscape. When out of sight of the camp the only sure way of returning was to follow one's tracks back. Finding the anxiety from the possibility of the men missing the camp and getting lost too great, we made breastplate harness for the last camel and made him drag a heavy chain, which cut a small furrow in the ground sufficiently deep to be followed for a month or two after it was cut. The blowing sand would obliterate the furrow in places, but we were always able to pick it up farther on. In the Winnecke Creek country the ground is hardened clay, with shale in places, and if a strong wind was blowing all traces of the pad made by twenty camels were gone in half an hour. The timber, such as it was, grew thicker there than in the sandhills. It was the easiest thing in the world to miss the camp in that country, but the little furrow saved the party from accidents. It was in similar country to this that Anderson and Hitchcock recently lost their lives.

We left Oodnadatta on 17 February 1909, reached Alice Springs on March 13, left for Barrow Creek on the 16th, arrived there on the 28th, and left again on April 3, bound for Victoria river. By travelling in a westerly direction for a few miles we outran the fiat-topped line of hills in which lies the Barrow Creek telegraph station, and soon entered a dense mulga scrub, with much dead and fallen timber. The mulga grew so thickly that it was difficult to get through in places, and our track was sinuous, over perfectly level firm sandy soil. From the end of the Barrow Creek hills this mulga-covered plain looked drab and uninviting, and it extended to the horizon in the west and north-west.

We camped that night in the Hanson Creek and next day travelled north for 7 miles along the east bank of the Hanson to an old and apparently dry soakage well in the creek. We spent the rest of the day in getting down to water, which was 9 or to feet below the surface. We had to drive in stakes around the hole and weave them with bushes to keep back the running sand, but next day we were able to give the camels a drink from it. The Hanson Creek here has a wide bed of deep sand, and looked promising for a soakage that would last some time, so I decided to timber the well and make it a water that we could fall back upon in case of need. As Paddy had pointed out the site it will be referred to hereafter as "Paddy's Soakage Well." A sea of mulga scrub on level ground surrounds the well for many miles, and no hills or landmarks of any kind are visible from it.

Paddy was rather good at making "mud maps." These are drawn on the ground with a stick, and are the black fellow's way of showing where and how physical features of interest to him are situated in relation to one another. When requested to show what lay beyond, Paddy drew a map showing the course of the Hanson Creek (the native name is Ahgwaanga), also of the large Lander Creek (native name Allallinga) a good many miles to the west. He indicated certain conspicuous hills near the Lander and the sites of certain springs and soakages on the routes he had travelled, and, by marking his various camps, the time it took to travel from water to water. The production of this map of course took much prompting and questioning. I made a sketch of it which I found useful later on. Some of the "springs" according to Paddy were huge affairs, and one he said had a large open water. Upon inspection they proved to be small native wells or potholes sunk through the travertine limestone, and at the bottom of each perhaps damp sand, or at most a gallon or two of water showing. He was quite right however about the permanency of the supplies, for when we sank wells in the near neighbourhood we invariably obtained a copious supply of good water - as will be described later - and they proved extremely useful to us. A native, in his natural state, only uses water for drinking; it never occurs to him to wash.

On April 9 I took one of the boys and rode out 22 miles to a small hill from which I took the bearing of any hills rising above the ocean of scrub. A low ridge was showing on 358°, and the boy said that the Hanson Creek ran by the western end of it. He pointed to where the creek ends, on 350°, and to the springs, on 330°. Paddy's soakage well bears 232° from this little hill. The Hanson Creek had always been represented as running north-west, but from our camp its course was evidently much nearer north. The springs were however north-west, but the boy stated that a big soakage existed farther north, down the Lander, and that as the springs were far off we had better go there first, and from there make for the first spring.

Before starting I decided to make Paddy's soakage well as reliable as possible, so we sank it deeper and timbered it well. This took until April 15. On the 16th we started north along the east bank of the Hanson, cutting off the bends when possible. In 5 miles we passed over a hard clay pan, with a little water in it; it was nearly dry. It had a good catchment if rain fell, and there was a fairly good camping ground for either camels or horses on the western side of the creek, which here spreads itself out over the hard ground, but soon becomes more defined. At 10 miles from Paddy's well we reached the ridge above referred to which was composed of bands of quartzite, striking east-west, and dipping steeply both south and north. The ridge has received the name Adieu Ridge, and from it are visible low hills on 96°, high hills (? Mount Strzelecki) on 280°, and a pointed hill on 267°.

Next day we travelled 17 miles, still along the east bank of the Hanson, to Paddy's "big soakage," which we found as dry as a bone, but a freshet near the spot gave us a good temporary soak. The first 9 miles of the journey were well grassed and clothed with edible spinifex, but the rest was poor sandy country. Some hills 15 or 20 miles north-west of Paddy's well, which I visited later, have been named the Scott Hills, after Mr. F. R. W. Scott of Barrow Creek (the native name is Charra Charra).

On the 19th we made for the first, or nearest, spring, on bearings that varied between 294° and 303°. We crossed the Hanson Creek where it runs north-easterly, and at 4 miles struck very poor country, timbered with "bastard" box and stunted mallee. We passed over the crest of a sand-ridge, and then travelled in a wide sandy valley between a heavy sand-ridge 3 miles on our left and another 2 miles away on our right. At 7 miles a depression, timbered with limewood and titree, ran north and parallel with the heavy sand-ridge on our left. This ridge now ran diagonally across our path, and at 8 miles we began the ascent of a formidable series of sandhills, crowded close together, the eastern edge of which bore round to the north-west in a semicircle. At the summit we noted in the distance a low-lying circular hollow a little to the right of our course, and Paddy immediately suggested altering our course towards it. After travelling over much loose blowing sand we began the descent to the hollow. It was evident that we ought to have followed a slightly more northerly bearing, and saved ourselves the ascent and tiring travelling over some 7 miles of very heavy sandhills. Down in the centre of the hollow Paddy picked out two natives half a mile away and asked me to stop the caravan while he went down to them. As soon as they saw him approaching they made off for their camp, but halted when he called to them. He soon beckoned us to come on down, and the natives then led us to the first spring, which was in the centre of the hollow. The so-called spring was an oblong hole sunk through the travertine limestone crust into the horizontally disposed sandstone below. The hole was sunk on the incline for 5 or 6 feet, and at the bottom there were about 5 gallons of water. Upon bailing it out we found that the water rose again to the same level, but without a lot of work we saw no prospect of watering twenty camels from it, so we camped and decided to go on to the next spring next morning.

Paddy warned us that poison-bush grew in the sandhills a short distance north, a fact we verified next day. It proved to be a species of Gastrolobium - probably G. grandiflorum. He stated that it infested all the country along our route from this spring (hereafter to be known as Circle Well, for on the return journey we sank a well close to the spring) to Giant Well, and extended in a wide belt westward to near the Lander Creek. I knew the bush very well, but up to that time had only seen it grow near to or on sandstone ranges in Central Australia, and mostly in small creeks that rise in such ranges. Here I found that the bushes grew on the sandstone hills, on the sandhills, and all over the sand plains as well, and very thickly too in places. A few mouthfuls of this bush and a camel is settled, unless an antidote is administered quickly, and even then it sometimes takes weeks, or even months, before the animal gets well. We had to be most careful of the camels while travelling through the Gastrolobium country, and where it grew thickly we tied their jaws together to prevent them snatching bites from the bushes as we travelled along, and we shepherded them very closely while they grazed. I was surprised to find the natives knew the deadly nature of the. plant so well. They will not camp under the bushes, and say that if they did harm would come to them. It is evident that the emu can eat the pods with impunity, for the seeds may often be seen in their droppings.

I asked Paddy why the two natives ran away when he was approaching them, knowing that he knew the language and had travelled extensively in the "spring country." He said "they were so sorry to see me come so far alone" (they had then not seen the camels) "that they ran to their camp to get their stone knives to cut themselves." In that part of the interior every native man has great scars across his thighs, one above the other, between the knee and hip, that mark the sites of deep terrible cuts he has inflicted on himself at different times when some relative has died, or some other great sorrow has fallen upon him. I have occasionally seen natives shortly after they have cut themselves, and the gashes were so deep one wondered that they did not bleed to death. They are forced to lie up for several days afterwards, and go limping for weeks and even months.

On the 20th we started for No. 2 spring. We had not gone far, perhaps half a mile, when the boys pointed out a Gastrolobium poison-bush. In 4 miles low sandstone ridges began and continued until we reached 7 miles from camp. Much Gastrolobium grew on them. Before we descended from these ridges on to a low-lying valley we saw that heavy sandhill country lay in front of us. The plain, or valley, had low titree growing on it in places. At 6 miles we came to No. 2 spring and some sandhills. From No. 1 to No. 2 spring is 13 miles. Our general direction was north of west, the directions from water to water will appear later on. This No. 2 spring proved to be a shallow native well, in a titree swamp. We sank a large hole a little distance away in sandy ground and watered the camels, the ground being "full of water." The camels were shepherded on the plain and tied up for the night. Poison-bush grew very near the camp all over the sandhills. Next morning we started for No. 3 spring over sandhills thick with poison-bush. In 3 miles we came on a small titree swamp, and in another mile a titree watercourse, or perhaps more correctly a long swamp in the sandhills. There was a native well in it and the water was very near the surface. At 8 miles from camp we came on another titree swamp with a rather large native well in it, at which we camped, with poison-bush all around. On the return journey we sank a well here, getting plenty of good water, and it now bears the name of Fulge Well. This apparently was No. 3 spring, but as a matter of fact all the hollows we had passed, and others for many miles yet to come, appeared to have water in them, very near the surface.

We started on next morning over, and also between, sandhills. In 4 miles we came upon bloodwoods, whitewood, and titree, with poison-bush around, and at 6 miles the sandhills were thick with poison-bush. For the next 2 miles the sandhills were more broken, and then we ran into a flat with grass and low titree, whitewood, and a variety of paper bark new to me. The ground fell away to the north-north-west, the sandhills fell back on either side, and descending on to a flat we were gladdened by the sight of clumps of beautifully green wattles, and in one clump was a native well. This well was a hole, 2 feet 6 inches in diameter, sunk through a travertine-limestone crust, that widened below into the dimensions of a fair-sized round galvanized iron tank, with water showing about 4 feet below the surface. I tried to get the boys to go into the well and clean it out, but they said a huge snake lived in it, and nothing would induce them to get into the well. I had to get in myself, the boys watching meanwhile to see the snake make a meal of me. We cleaned out the hole and watered the camels from it, and it now bears the name of Wattle Spring. The flats around grew samphire, and the camels grazed thereon with apparent relish. They eat the wattle also and fared better at this camp than for some time past, having had to be shepherded very closely to keep them from eating the Gastrolobium.

Next day, April 23, after watering the camels, we started for Paddy's "big spring." We travelled first over the plain, which was covered with samphire, and on which water lies for some time after heavy rain. These conditions lasted for 3 miles. A mile and a half from Wattle Spring we passed a native well, with water showing at 4 feet 6 inches below the surface. At the plain's end we struck and had to cross on the angle some steep sandhills, and at 4 miles were in a perfect jumble of sandhills. From the top of these we could see a heavy sandhill about 3 miles away on our left. This extended to the west-north-west, where a tableland continued on to the north-west broken by a gap right on our course. We ran down a sandy slope into a deep hollow that lay between us and the tableland. At the bottom we came to a shallow watercourse that ran south-east across our route, with a clump of wattles in its bed in which was a shallow hole with a little surface water. A hundred yards or so to the south-west was a native well, in sandstone that outcropped in the watercourse. The water was only a couple of feet from the surface, perfectly fresh, and the supply inexhaustible, as we found when making the native well into a proper well at a later date. It is an unfortunate circumstance that that portion of the so-called "spring country" through which we had just travelled is practically useless for stock, being not only a wilderness of heavy drifting sandhills, but, what is far worse, also infested with the poisonous Gastrolobium plant. On the sandy slope to this water, now known as Giant Well, we saw the last plant, and the natives assured us that this is its northern boundary. Had the "spring country" been only moderately-well grassed and free of poison-bush, it would have been of considerable value, for fresh water, at very shallow depth, is obtainable in every hollow between the sandhills.

From an eminence near Giant Well I obtained prismatic compass bearings to a high hill on the Lander, 191°. It appeared to be 6o or 70 miles away. Scott Hills, 151.5°; Mount Denison (or what I took for Mount Denison, on the Lander), 184° ; Mount Strzelecki (?) 121.5°; and the end of the Lander, according to the natives, 347°.

We reached Giant Well on the 23rd and remained there the following day, enlarging the well, watering the camels, and making up the map to date. On the 25th we started for the last spring that Paddy had seen. In 1 mile we crossed a sandstone outcrop, and half a mile beyond that we passed a quartzite quarry where the natives manufacture their stone knives. At 2 miles we passed, to the south of our course, a spot with wattles growing around, where water evidently exists very close to the surface. At 21 miles we crossed a low watershed, and at 3 miles some small clay-pans. To the north and north-west were flat-topped sandstone ridges. Sandstone outcropped in places along our route, which was timbered with a line of limewood gum trees, wattles, and titree, with grass in places, and spinifex with edible tops. I have not mentioned spinifex much so far in this record, but it is omnipresent in this part of Australia, on the sand plains and sandhills, in the hollows, on the rocky hills ; in short, it is ubiquitous. The sandhills seen from near Giant Well, to the south and south-west, ran on north-westerly in a continuous line, and were now not far from our route. At 6 miles from Giant Well we came to a sandstone ridge, and running north-west from it was a small watercourse, with a native well in it. From the highest point of the sandstone ridge the well which we sank here bears 295°. It is now known as End Well. It is about one-third of a mile from the ridge. On 292° are the tops of two sandstone rises. Limewood gums continue on to the westward of End Well. We were hoping for some hills, or some distinctive landmarks, along our course - which was north-west - but the outlook from this sandstone ridge was not hopeful. On all western points right round to the north-east was a perfectly level horizon, a sea of sandhills as far as the eye could reach. We appeared to have come to the limit of the sandstone formation which first out-cropped near Circle Well. Geologically I take it to be younger than Adieu Ridge on the Hanson, which may be pre-Cambrian. This sandstone formation is, in my opinion, of Palaeozoic age, and may be Cambrian. It is much fractured and disturbed in places, though its general disposition is more or less horizontal.

End Well being the end of everything so far as Paddy's knowledge went, we now availed ourselves of the offer of several natives who had come to visit our camp, to show us a spring they knew of bearing north-north-west. It is quite impossible to keep on a given bearing when following a crowd of natives who are hunting rats, cats, lizards, etc., on the march. They spread out in crescent form, and throw boomerangs at anything they disturb. It is little use the animal trying to escape, for some boomerang is almost certain to hit it. If it elects to crouch in a bunch of spinifex, as the cats often did, it is speared. On this march, and on several other marches, we saw the wonderfully accurate way in which a native can throw a spear. In almost every case the spears went through the animals. This country was so thickly stocked with rats and cats that at the end of the day's march a great number would be brought into camp by the natives, and my men named it, and afterwards referred to it, as the Rat and Cat Country.

On the 27th we started from End Well, following the natives first north-west, then north, north-east, and east to a hollow surrounded by blowing sandhills, the floor of which was a crust of travertine limestone, or perhaps more correctly, calcareous sandstone, through which was a hole several feet long and 5 or 6 feet wide. The native well was sunk in sandstone below this crust for 3 or 4 feet to water. I calculated the distance from End Well straight to this water-hole at 14 miles, but the route the natives had brought us was very circuitous. For the first 3 miles the country had grass - fair pastoral flat land. There were low sandstone rises on our left, then low sandhills to 7 miles, and a little farther on a quartzite outcrop, and a hollow in which grew whitewood gums. This continued for 11 miles, when we entered a sandhill country, the sandhills running east and west, and continuing to the so-called spring. All the way was sparsely timbered, and as we neared the spring sand was blowing. The spinifex en route grew tops. The next two days we spent here, sinking a well for 6 or 7 feet in the sandstone below the crust, but the supply not being sufficient for our needs we bored in the bottom a few feet, when a good supply of fresh water rose 5 feet in the well. It was a desolate spot, and the well is named the Hit or Miss Well.

On the 30th we started for another so-called spring to which one of the natives had agreed to pilot us. This lay north-westerly from Hit or Miss Well. Soon timber appeared on our right. At 3 miles a titree hollow, and our guide said there was water on our left, but we did not see it. At 3.5 miles we passed a native well in sand; but there was no water to be seen in it. At 5 miles the edge of the timbered country was on our left; it consisted in part of bloodwood and limewood. A long low rise with a flat top was visible from here to the north, perhaps 5 miles off. At 6.25 miles the ground was strewn with brown ironstone rubble. At 8 miles we were on the top of a slight rise, with a hollow to the south, and another to the north, the latter rather pronounced. Then came bloodwoods and limewoods, the timber getting more open as we travelled along, and a small grassy flat close to camp. Davidson's track, so the native said, was near this camp; but the blowing sand had obliterated all trace of it.

Next day, May 1, in 2.5 miles we had passed over the rise and were in a depression which ran round like a horseshoe to the west of us, and where we crossed it a few limewoods were seen. In 3 miles we were on the top of a rise, with a hollow to the north. We then ran along a mallee-timbered rise for 2.5 miles, and then through a depression, with mallee. At 9 miles from starting we passed out of the mallee and entered a thicket-like scrub consisting of green sticks, used by the natives for spears, and the bark and leaves of which resemble wattle. As we approached some sandhills the undulations grew shorter. A very poor country all the morning for stock feed. At 10 miles from camp we came on the first of several sandhills ; at 10.5 miles a dry native well. At 14 miles we camped, in a fine run of limewoods, which ran along under the northern lee of high sandhills on our left. From the native well to camp titree grew between the sandy rises, which appeared to end here ; but on our left there appeared to be a vast tract of sandhill country.

On the 2nd, in 3 miles from camp in limewoods, we passed out of timber and then over a low saddle. Here there was a thicket of the hard sticks, like wattle, on our left, and rising ground on either side. At 4 miles from camp the sand and sand ridges fell away, and we ran down to a titree-covered lowland. In the far distance, north-westerly, there was visible what might be a tableland, or perhaps sandhills. At 5.5 miles I noted a patch or two of travertine limestone on the plain. Here and there a solitary limewood grew, with semi-thickets of the hard wattle, and titree. These features continued until we arrived at the so-called spring, which was 6.5 miles from camp, and 32 miles from Hit or Miss Well.

This native well was in a thicket and the water was in a hole, or cleft, in travertine limestone. After some work we succeeded in watering most of the camels from it, and then we tested the ground by boring, in a more convenient site. On the 3rd we started a well on the new site, and finished it next day. Not-withstanding that it was winter we had a couple of roasting-hot days here. The well is in a titree swamp. There is a green swamp with samphire and other camel feed surrounding a red sandhill a short distance from the well, and from this delectable spot the well derived its name, Green Swamp Well. Like all the others along the route, it is shallow and yields a good supply of excellent drinking water. There is a little grass in the low-lying swampy area here which, by the way, is of some size, and the camels found much better feed here than at most of the camps since leaving the Hanson. The only other grassy stretch is from Giant Well to End Well. Travertine limestone is visible in several places over the Green Swamp hollow and doubtless water in endless quantity lies beneath all over it at very shallow depth.

Davidson's Duck Ponds, on Winnecke Creek, were our objective when we started out from Green Swamp Well on the 6th on the bearing 312°. Mallee began near the well. At 4 miles we topped a long sand-ridge that had been on our right. From the well here there had been grass and spinifex tops, fairly open country. From the crest the great hollow we had just crossed was conspicuous. At 7.5 miles from camp the ridge we were on, of nearly flat firm sand, appeared to be rising to the south-west and falling in every other direction. There were sandhills to the north-east in the distance, and lower ground on all the northern horizon. At 10 miles we were on a high sand tableland, with a heavy depression on our left running round in front of us ; the bottom of the hollow appeared to be about 5 miles away. The land was falling on our right also, with sandhills showing 2 miles off.

At 12 miles from Green Swamp Well we camped. There were several trees resembling the paw-paw tree about the camp. Next morning we continued on the same bearing, and in one mile were in a hollow that trends east and west. At 2.5 miles we were on top of a sandy ridge. Corkwood - always present in desert regions - was the dominant timber of this part. At 3.5 miles there was a hollow to south-south-east, and apparently a titree swamp. Sand rose all along the southern horizon. We could see 20 miles. To north the ground was rising. At 13 miles we camped. For the last to miles the land was gently undulating. For the last mile or two there were a fair number of paw-paw and bloodwoods, of the mallee type. A poor variety of bloodwood was seen all day, and clumps of mallee. Along this march the spinifex had been recently burnt, and the ground was a charred mass of low sand heaps. The heat was oppressive all day.

On the third day out from Green Swamp Well, April 8, we started still on the bearing 312°, and ran down a long depression between two lines of sand-hills a good way off the line of route. At 6 miles we struck a box swamp and then marched for 4 more miles on the same course, skirting, on the north, a thick scrub. Titree now became plentiful, and spinifex very dense. We turned west-south-west for 3 miles, and again to north-west for 1.5 miles, then camped. This third camp from Green Swamp Well was a poor one for the camels. Next day we returned to the box swamp seen yesterday and sank a borehole 9 feet, but got no water. The sinking was hard, so we decided to return to Green Swamp Well, water the camels, and try a more southerly route, as the one we were on was on comparatively high ground. Next day we returned along our outward pad and camped 13 miles north-west of Green Swamp Well. On the 11th we reached Green Swamp Well. The camels had been six days without water, save a couple of buckets we gave each from what we carried. We spent the next two days putting a set of timber around the mouth of the well, and mending saddles. A black fellow, who with his wife and two children visited Green Swamp Well, reported that a native well existed on the bearing 280° from the well, and another on 216°. He promised to take us to the former after he had visited the latter, but failed to turn up as promised.

On the 14th we started on our second try for water on 280°. In 4 miles the sandhills fell off and we entered a plain with desert mallee, and at 6 miles a low sand ridge appeared on our right. At 8 miles the poor timber grew sparser, and the country was very poor. Higher country appeared to lie to the north and north-west. At 13 miles we camped in hedgewood, with not much feed, and the camels were inclined to wander. A good many trees, resembling the Moreton Bay fig tree, grew about this camp. In the evening I noticed Tim, the black boy, making a stone pick, which he said would be a good fighting weapon. Next day we found that both our black boys had decamped in the night. The camels had wandered far by the time we overtook them - the boys usually brought them back each morning - and it took the whole day to get them together.

We now travelled 7 miles on the same course as before and camped on a burnt patch that grew a runner-plant that the camels seemed to appreciate. It was green and succulent, but there was not much of it. The whole area was one of sand, in long undulations culminating in a sand ridge every 3 or 4 miles. It was terribly desolate country. I decided to leave the camp where it was and take Baxter and three camels and prospect ahead for a day or two. So on the 17th we started on 280° over sandy country clothed with tall mallee, then along elevated land with here and there patches of Moreton-Bay-like trees. We then turned due south, and at 6 miles were on the top of a high sandhill. To the west-south-west was a hollow, with rising ground in the distance. Southwest the landscape was similar, and we could see no change for 30 or 35 miles. To the south and south-east were big rolling red sandhills as far as the eye could see - a most hopeless outlook for 15 or 20 miles ahead. This was the worst of many bad places we got into in searching for sites to bore for water. We travelled 1 mile north and camped.

We saw the tracks of two natives while travelling, but failed to find their water. On the 18th we travelled straight back to where the party were camped, and on the way saw a flock of grey top-knot pigeons, so there must be some surface water about. On the 19th I took Baxter and two riding camels to try and find the water the pigeons were drinking from. We first went east, then south-east, then south-west, then north-west back to camp, which we called Pigeon Camp. At the farthest point out we saw some gum trees, but failed to find the water.

The camels, having grazed on the runner-plant, were not yet very thirsty, so I decided to take the whole party and try the country between the two outward routes. We travelled on 50°, over a "blowing-sand" area with heavy undulations, the whole way. We got a surprise at 3.5, and again at 4.5 miles from Pigeon Camp at seeing the tracks of one bullock. At the latter distance we dropped on to a plain; at 5.5 miles we were again on top of a high sandhill from which we saw a titree swamp a mile and a half to the north. We went to it, decided to bore, and at 9 feet 6 inches from surface struck a fair supply of fresh water. We then started a well and got down 2 feet on this day also. Next morning we found that the water in the borehole had risen to within 3 feet of the surface. We worked with a will, for the camels had been without water for eight days, and were thirsty, and by 11pm finished watering them. The well is named Cattle Swamp Well, and from it the high sandhill from which we first saw the swamp bears 197°. A big red sandhill bears 177°, and a small hill in the far distance with a peak top 327° (doubtful).

On May 23 we started on the bearing 327°. At 2.5 miles we came on two small titree swamps in low sandhill country, then an open plain; at 5 miles more sandhills, which ran about east and west. As we crossed these I saw, on a small plain between the sand-ridges, several mounds of rock 4 and 5 feet high, amongst the limewood gums that grew on the plain. To see rock outcropping through the sand was most unusual. Ever since leaving End Well sandhills and sand plains had prevailed. I did not go over to these mounds, but took them to be formed of grey limestone. The sand-ridges were four in number, and at 6 miles we were through them. From the last one we saw, to the south-west and west, belair scrub and flat country with bloodwoods growing over it. A little north of the last sandhill was a titree swamp, that ran parallel with the sand-ridges, and over the level ground around limewood gum trees were scattered. Then followed another sand-ridge, and again at 8 miles from Cattle Swamp Well another run of titree swamps parallel to the sandhills. On this No. 3 titree swamp we camped. We saw a good many galahs and white cockatoo parrots with pink breasts in the sandhills 4 miles back from camp. Limestone outcropped in many places between the sandhills we crossed on this march. The limewood gums and the bloodwoods were large and looked fresh and green from the tops of the sandhills. From the turkey and emu tracks that we had seen and a bullock track only three or four days old, we concluded that there must be surface water about. The country also must be low-lying, for titree swamps were numerous.

On the 24th we continued on the same bearing, 327°, over recently burnt country. The firm sandy surface was gently undulating, and clothed with very open titree scrubs and a poor desert variety of box. The ground grew harder as we proceeded and looked as if it were swampy and boggy during heavy rains in the rainy season. It looked poor land, with little or no grass, but the fact that the whole country had been burnt made it difficult to judge. There were low sand-ridges on our right. At 10 miles there was a sandy rise, and at 12 miles we had to bore our way through belair thickets, and ironstone pebbles covered the surface. We ran down a steep slope into a grassy watercourse and camped in it, at 14 miles from the last camp and 23 from Cattle Swamp Well. The watercourse was simply a grassy flat - not a creek. It had one bunch of mulga in it - the first mulga we had seen for a long time. There were plenty of limewoods, well-grown corkwoods, belair, wild rose bushes, and a variety of wattle on both sides of the watercourse. The prospect was quite pleasing when compared with the dismal surroundings we had been in for so long; but the grass was dry, and it was a terribly dry time here. There was rising ground to the west and south-west, and in front of our course a distinct rise - almost a hill.

This sandhill tract of country gave me the impression that at one time it was a vast hollow, before utter desiccation set in, and may have been filled with water. The Lander poured its flood waters into it, and possibly the Hanson and Winnecke creeks as well. In addition to the sediment brought into the hollow by flood waters, very much larger quantities were transported thither by wind. This latter agency may not have been so active at first, but in later time, and right on to the present, wind has been the major transporting agent in filling the hollow. It appears to be nearly filled at the present time. A remarkable feature of many of the hollows on its present surface is the continuous water horizon lying very near the surface. This is frequently indicated by a crust of travertine limestone of varying thickness which probably was formed when the water-table rested sufficiently near the surface for moisture to be drawn therefrom to the surface and evaporated by the sun's heat, leaving its lime content as a precipitate in the sandy surface layer, in which it has acted as a cement, and formed a crust. It is evident, from the fact that the horizontal limestone crust runs away under the giant sandhills in places, that the sandhills are encroaching on the hollows. It is possible also that on the opposite, or north-western, side of the hollows the sand may be travelling away and leaving further flat moist surface areas on which a limestone crust can form.

In some of the wells we sank we found more than one band, or layer, of limestone, which pointed to a gradually rising water-table - a thing quite possible where a hollow formed of impervious rocks is filling with sand, on which there is a fairly good annual rainfall. As the rain falls here it immediately sinks into the sand and, percolating downwards, reaches the water-table. It is only in the hollows that the water-table is sufficiently near the surface for evaporation to take place and, incidentally, form limestone crusts - a process that has been going on for ages past, and is likely to continue for ages to come. Herein lies my explanation of the quite phenomenal long line of shallow permanent waters we met with between Barrow Creek and Victoria river. Without the covering of sand the water would have been evaporated long ago, for the average annual precipitation over the area is io to 12 inches only; while the evaporation is not less than 12 feet.

At this, Wild Rose, camp a distinct change had taken place in the geology of our surroundings. Sandstone and shale, with ironstone conglomerate, underlay a thin sandy surface, down through which this blind watercourse had cut its way in long-past ages. The geological age of the shale formation we had now reached is uncertain, but it is evidently much younger than the sandstones between Circle Well and Fulge Well, and between Giant Well and End Well. Lithologically it bears little likeness to anything near Barrow Creek. It forms the north-western edge of the sand-filled hollow we had just crossed. It continues from here north-westerly to Victoria river. I believe it to be older than the basalts of Victoria river, the Great Antrim Plateau, and Renner Springs, near Powell Creek. It bears a close resemblance to the shale formation that occurs between Banka and Renner Springs, on the Overland Telegraph Line. It may belong to one of the younger Palaeozoics, or even be one of the Mesozoics. Between Wild Rose Camp and Victoria river it gently undulates. The wide trough-like hollow in which Winnecke Creek runs cuts deeply into it. The formation varies in character, being for the most part dark purple in colour, and is composed of layers of sandstone, massive for the most part, but occasionally flaggy. Thick bands of shale and bands of haematite are striking features in several localities. Bands of conglomerate also occur in places. These rocks gently undulate, but they are not greatly jointed or disturbed, at any rate "regionally." Evidently, by the colourings on his map, Davidson regarded the Buchanan Hills as of this formation. He was probably right. The best sections seen by the writer were along the course of Winnecke Creek. The strata there are mostly of ferruginous sandstone, horizontally disposed - thick flaggy layers with which much haematite is associated. Back from the creek for considerable distances, especially on the north side, the ironstone forms small hills at Ross Gap.

On the 25th we left Wild Rose Camp and proceeded on the same bearing, 327°. Limewoods continued for 1.5 miles. After a gentle rise for 7 miles a slight fall was apparent to the north-west. The country was fairly open and covered with spinifex, but no grass. At 11 miles from camp a low line of red hills was visible to the east. The same may be a continuation of the "conglomerate hills" of Davidson, for our lines of traverse converged here and continued so to Winnecke Creek. The gradual descent continued to 14 miles, where we made camp. Turpentine bush grows all over this shale and sandstone formation, sometimes singly, but mostly in thickets. This vile sticky bush has taken the place of other bushes to a large extent. Instead of the soft sand we had travelled over for so long, this day we had hard red sandy soil all the way, the camels scarcely making a mark on it. As we travelled over it the ground looked perfectly flat : it was only in the distance that an incline or decline became apparent. From our camp rising ground was showing to the north-west, a good many miles away. The most conspicuous portion of the low conglomerate range, or rise, for it was not a conspicuous feature, bore 97°, but the outline extended along the horizon from 8o° to 105°. The range appeared to be 4 or 5 miles away.

On the 26th we left Conglomerate Hills Camp, continuing on bearing 327°. Scrub gave place to open country, and a ridge 11 miles on our left completely shut out our view in that direction. At 5 miles we seemed to be on the top of a dome with a wide valley between us and the conglomerate hills. At 8 miles, when passing over a bare patch of shale, I was surprised to find a hole, like a round well, going straight down into the shale for 20 or 25 feet and then a passage led off horizontally. All the rain water caught on the bare shaly patch of rock ran into the hole and from it into the underground passage, making thereby a short cut to lower levels. The sides of the hole were waterworn and smooth. We did not descend it to explore the passage but passed on, and at a quarter of a mile from the hole a conspicuous landmark, in the form of a small cone-shaped hill, showed up on a bearing of 233°. The hill appeared to be 8 to 10 miles away. Davidson saw, but did not name, this hill, so it now bears the name Lothario Hill. This is the only conspicuous landmark we had come across for many a day. Those who have not travelled over a tract of country of such dimensions, absolutely devoid of conspicuous landmarks, can hardly understand how dreary travelling becomes, and how monotonous, when surrounded by low scrub that shuts out the view in all directions, pushing a way through them day after day and week after week, with not a sound but the pit-pat of the camels' feet on the ground, and the creak and groan of their loads, as they stalk majestically along. Surroundings like these are productive of sensations that incline to the serious. The lives of the whole party depend on making no mistakes. The success or failure of such journeys depend on knowing how to handle the camels and on being able to judge accurately how far each animal can carry the load assigned to it without a drink. Our camels were good and sound. My companions were loyal, and I never heard one word of fear, or a complaint, from any of them, and so we got along well, and each day brought us nearer our journey's end.

The sight of a hill put new life into the whole party, for we now knew that Winnecke Creek was not many miles away, and that there was a chance of finding water in some of the water-holes along its course. From the peculiar hole we ran down a very gentle slope and camped in a belt of rather well-grown bloodwood timber. The low ridges we passed over on this day's march, inclusive of the one with the remarkable hole, were capped with ironstone conglomerate. The sandstone and shale formation occupies the whole country, although often hidden by sand on the gently inclined slopes and hollows; the strata lying for the most part quite horizontal. From the rock-hole eminence the horizon-line to the north-east looked like a low broken tableland, and rising ground extended right round from east to south-west. The ridge on our left fell away and a valley succeeded, which appeared to run parallel to our course. It was beyond this valley that the cone-shaped hill stood out plainly. Although quite a small hill, it was, I repeat, the most conspicuous landmark seen since we left the hills near Barrow Creek. It impressed us greatly, being such a contrast to the gentle rises and hollows that obtain in a country devoid of any striking physical features. Monotony is the dominating characteristic of Central Australian scenery.

On May 27 we left Bloodwood Camp and continued on 327°. We had practically level country for 5 or 6 miles, timbered with mallee, box, belair, turpentine - scrub the whole way; then gently-rising ground until 10 miles from camp, where ironstone conglomerate formed the surface. The flat land here terminates suddenly, and there is a steep descent for 1 mile that runs down to the Winnecke Creek, the spot being about 5 miles north-easterly from Duck Pond water-hole.

From the top of the ridge that overlooks the Winnecke Creek the box timber in the valley seemed green in comparison with the sombre surroundings. This part of Winnecke Creek is peculiar, as one may cross its bed in places and not know that it is a creek. In its upper part it is a well-defined and sandy bedded watercourse, but here in places it is simply a grass-covered flat, with nothing to show the direction in which the water flows. An occasional scraggy box tree however marks the course of the water. The creek rarely gets flooded throughout its whole length, but it is evident, from the occurrence of large water-holes-at intervals of, say, 1 to 3 miles, that great floods occur sometimes. By following along the grassy flats one comes upon the end of a tiny rivulet, which soon increases in size until it forms a creek, leading down a gentle slope to a water-hole. Several of the water-holes are of considerable dimensions and hold water for several months when filled. The watercourse on the other side of the water-hole gradually diminishes in size, finally ending as it began, in a grassy flat. On following the grassy flat still farther one finds that the whole thing is repeated. In this way several very good water-holes occur. We hit the creek right on one of these washouts. It was a quarter of a mile long, and in the northern end were two pools of water in the bottom of holes to feet deep. Only i8 inches of water remained in this water-hole, which is not one of the best in the creek. The water was sufficient for our purposes however. This and some other of the holes have conglomerate bottoms, and hold well. The ground along the creek and the grassy flats is hard clay, and as each water-hole has a good catchment area of its own, the holes get filled whenever a good shower of rain falls. I would not consider any of the holes I saw as permanent waters, but they hold for a long time after the summer rains, and in one water-hole there is a soakage to be had long after surface water has gone. Farther up the creek at Ross Gap there is a good soakage in the sand. It had water each time I passed there, but whether permanent or not I cannot say. Excepting the small pool at Giant Well this was the first surface water seen since leaving Barrow Creek. From Bloodwood Camp to Winnecke Creek was 11 miles. We camped at the water.

We remained at Winnecke Creek the following day, May 28, to allow the camels to feed, but next day we started for Victoria river. We first made a slight detour easterly to escape some thick scrub, and to take advantage of a long valley that ran north to obtain good travelling for the camels. At 6 miles from Winnecke Creek we saw a large expanse of bloodwood to the south-east on a plain, with dark foliage in the distance; at 8 miles a deep valley on our right, with green trees in the hollow. Our bearing was now 360. At 10 miles we struck a black line of timber, which was composed of native orange, supple-jack, creepers, etc. - splendid camel feed, but there was no creek. Here we made our camp. We had had exceptionally heavy spinifex for the last 2 miles. The ground is here so hard and dense that when heavy rain falls the country swims with water. The spinifex grows in great bunches 4 feet high and several feet across at the base, forming quite a formidable obstacle to travel.

On May 30 we continued on same course for 2.5 miles, then changed to 315°. We first crossed a grassy and splendidly bushed plain, subject to periodical flooding in the rainy season, then a depression, and then more open country that resembled a water-parting. At 6 miles a little travertine limestone appeared on the surface for a mile. At 8 miles we were in a bloodwood and gum-tree valley, and at 10.5 miles bush came in, with level ground to the west and a ridge 2 or 3 miles off on our right. At 15 miles we camped on a water-parting, with box and mallee around.

Next day, still on the same course, we first crossed a depression, but after 5 miles spinifex gave place to grass for 2 miles, then well-grassed timbered and bushed country followed. For 5 or 6 miles we travelled over an older rock formation than the purple shale of the tableland. This older series had undergone considerable disturbance. Slate and shale formed the tops of the rises, while limestone succeeded below. There were outcrops of limestone at intervals, and the surface was strewn with pebbles of slate, shale, quartzite, sandstone, and limestone. A great view was obtained from the hillocks, extending right round the horizon, except to the north and north-east. We passed out of the limestone and bloodwood area at 11 miles. From 11 to 12 miles there was a fine grassy plain with stunted box timber, then spinifex as thick as ever to 14 miles, and we camped at what we afterwards referred to as Corkwood Camp.

On June 1 we were still on the same course through mallee, corkwood, and dense spinifex country. At 6.5 miles we crossed a run of paper bark trees, quite a new feature, then poor country to 12 miles, where we were down in a hollow, with a little grass and a horse pad showing. At 13 miles we camped, having passed over a grassy swamp for the last mile. Here we saw a cat and a quail, and horse and cattle tracks.

Next day we travelled on the same bearing and in half a mile came on more new cattle tracks; at 2.5 miles we were on a rise strewn with ironstone rubble, and at 5 miles on a slope that led to a creek, which we reached in one more mile.

We followed the creek south-east for 6 miles and then camped, but all the water-holes in it were just dry. Cattle tracks and pads were numerous. Next morning we travelled back along the same pad we came by to the point where we first struck the creek, then for 2 miles on 257°, and, seeing cattle about, camped, thinking their watering-place must be near; but we failed to find it.

On the 4th, taking Baxter with me and a couple of riding camels, I went west-south-west along the course of creek and found some shallow clay-holes with water, where the cattle watered. The water was pretty muddy, but drinkable when cleared. The rest of the team arrived later, and we camped. We stopped here two days and then started on 207° for 5 miles, then on 10° for 4 miles to the head of a creek, which we called Horse Creek. We followed it down a steep descent, over many ledges of sandstone, slate, and basaltic-ejectamenta rock, and camped. We had now reached the southern edge of the large basaltic area of Victoria river. The tableland here breaks up into a number of isolated flat-topped hills, remnants of a partially eroded tableland.

Our way now led nearly north over rough basalt country to a small creek near two hills, called the "Sisters." They are not far from the Camfield river, a tributary of Victoria river. On June 9 we first travelled on the bearing to° and in 1 mile struck a fairly large creek and followed it down for 11 miles; it ran about due east. Later we found it to be the head of the Camfield river. We then followed the tracks of a newly shod horse, driving cattle, for 2 miles, and then camped. We had passed by many water-holes on the way and numerous billabongs on the sides of the main creek, which was lined with large box-trees and guttapercha. All the previous day and this we passed through basalt country splendidly grassed, but we saw no water. After making camp I walked north-north-west to a hill, and from it saw a table-topped range to the north-west a few miles off.

Next day we travelled on the bearing of 328° for 2.5 miles, then on 338°, and at 4 miles were on a watershed, with the four prominent hills of the range in sight. We then travelled on 311° to the south point of these hills and camped, at 13 miles from our last camp. Upon climbing to the summit I was pleased to find that the hill was one of Mr. L. A. Wells' trigonometrical stations, named South Point. The Adelaide Survey Office had very kindly given me, just as I was leaving Adelaide, the first rough pull of Mr. Wells' map of Victoria river and district, on which this trigged hill was shown. We were now aware of our exact position - a few miles east of Wave Hill cattle station homestead on the Victoria river. As we had left Barrow Creek on April 3 the journey across had. taken ten weeks all but one day.

On June 11 we travelled south-west straight for the Croker Yards, and in 1 mile after starting met Mr. Seale, the manager of Wave Hill cattle station. He seemed to be greatly surprised at the size of our caravan. I was pleased to accept his cordial invitation to visit the station. Wave Hill at that time carried about 70,000 head of cattle, and the adjoining station - Victoria River Downs - about 120,000. The splendid pastures and magnificent water-holes of Victoria River are too well known to need commendation from me.

The Return Journey

Our outward route north from Winnecke Creek to Victoria river had been too far east, so on the return journey we first travelled to Mucka, an outstation of Wave Hill, to get a supply of salt meat, and then to the big bend of the Victoria river, the most south-easterly point on the river, at the Catfish Water-hole and Yards. It was from this point that I wished to open up a stock route as nearly direct as possible to Central Mount Stuart. Both Davidson and ourselves had failed to find Hooker Creek, and the inference was that it lay farther to the west than we had reckoned. I decided to try and locate a water-hole on that creek, and also a billabong a few miles out from Catfish Yard with the delightful name of Warcurracurra. A native woman was prevailed upon by the chief stockman at Mucka to pilot us there.

On 25 June 1909 we started, first following up a small tributary of Victoria river to its source, the edge of the tableland, 8 miles south-east of our starting-point. The tableland scarp is continuous, and too steep in many places for a string of loaded camels to surmount. From the edge of this tableland our course, although somewhat sinuous (for the native woman's route was "go-as-you-please," as is that of all natives) was nearly east, for 6 miles, where we struck the water. The billabong was a long wide clay-hole in a small creek. It is not a permanent water. When we left it perhaps 18 inches or 2 feet depth of water remained. It was of no use for my proposed stock route. It lies about south-east-by-east from Catfish Yard, and 14 miles away. From the edge of the tableland all the country from east round to south was clothed with spinifex, mallee, box, supplejack, peach, whitewood, and currant bush. Although practically a desert, I was assured by the cattle men of the country that the stock having access to the bush country seemed healthier and to keep in better condition than those that grazed only on the lovely grassy plains that border the Victoria river and its tributaries. The dividing line between the two totally unlike classes of country is here the escarpment of the tableland. In five minutes one passes from one to the other. The basalt soil is good - very good. The soil derived from the shale and ferruginous sandstone is poor for. grasses, but it grows edible bushes for stock and timber, and for that reason cannot be classed as "desert." But travellers invariably speak of it as such. The so-called tableland country extends along the route we followed from a little north of Cattle Swamp Well to Victoria river, and in an easterly direction probably to Banka Station and Renner Springs on the Overland Telegraph Line, as previously mentioned. According to Davidson extensive areas of it occur to the south-west, and run on to well over the Western Australian border.

From Warcurracurra it was necessary to go on a bearing a little west of south to try and locate the water-hole and billabong which rumour placed on the eastern end of Hooker Creek. On June 26 we bore away on 192°. At 4 miles we crossed the eastern end of a ridge capped with quartzite and ironstone. This ridge forms the watershed of Warcurracurra Creek. The southern slope beyond showed indications of considerable flow of water at times, but we saw no creek. There grew on it high coarse grass, and giant mallee and box, the drainage being towards the south-west or west. Then more spinifex and mallee, then more rises close to the route on the east side, and at 10 miles we crossed a small ridge, then mallee scrub and turpentine on and off until we camped in plumbush at 14 miles from our last camp.

On the 27th we continued on the same bearing, 192°, and soon were running along the western end of a hollow that ran to the east; along this watershed we travelled for 4 miles, then over a flat-topped tableland and down a slope, crossing a grassy swamp, followed by spinifex and mallee, and at 6 miles from Plumbush Camp struck gum trees and the edge of a broad grassy plain, on which for 2 miles the grass grew very high, evidently a flooded area in the rainy season. It proved to be the overflow of Hooker Creek. After crossing this overflow we returned to the gums and camped, the camp being 20 miles from Warcurracurra. After lunch I went down the watercourse and found no water, but the men found it in a water-hole 1.5 miles up the creek, west of the camp, in the grassy watercourse. It was of fair size, but not a permanent water.

On the 28th, after watering the camels, we started along down a branch of Hooker Creek that runs east on the whole but winds about a lot in its course, and in 5 miles we camped on the creek, which was quite a small affair, in a series of swamps. Next day, still following the creek for 7 or 8 miles, we passed a water-hole, just dry, named Two Dog Water-hole (as there were two wild dogs there) and crossed a swampy area on the way. At 8 miles the creek was evidently getting smaller and appeared to be losing itself in swamps, and as its course was too far north to follow any farther I changed to 132° for 7 miles and camped in corkwoods, having travelled 15 miles for the day. On the way we had a serious capsize, and several of the camels got rid of their loads. We tied the camels up that night as they would not stay, and started next morning without letting them go to graze. We had open level sandy burnt ground from the time we started on this bearing, timbered with a few scattered corkwoods and mallee. Next morning, on the same bearing, in 1 mile the timber changed to bloodwoods, which soon changed to larger bloodwoods, and gum trees came in, giving the appearance of a creek at hand. There was camel bush here also. This continued to 4 miles when, upon meeting with really good camel bush, supplejack, and several other varieties of creeper, we camped for the day to give the camels a good feed. We had had level ground from the Hooker Creek big swamp all the way to here.

On July 1, still on 132°, at 3.5 miles we were out of the good camel country and into scattered bloodwoods. A low dome on our course was just visible. At 7 miles we were on this rise, with ironstone conglomerate and ironstone rubble all over it, and at 8 miles the Buchanan Hills (of Davidson), a remnant of a former tableland, came into view. A cone on the north end of the tableland bore 187°, and the centre of the tableland 184° from here. No hills were visible in any other direction. At 12 miles we passed between two little hills. At 14 miles Buchanan Hills were full in sight, and the pointed hill at the north end bore 209°. We made camp near here among creeper, supplejack, and all sorts of camel bushes.

Next day we travelled on 177°, and in 4 miles struck Winnecke Creek. From here the pointed hill bore 225°. We followed east along the creek. It soon formed into two channels, with sandy beds, one of which ran south of east and the other north-north-east. Farther on the branch we were on split up again. It was evident that the creek, as a defined watercourse, was nearing its end, for it was spilling its banks all along, and ants' nests showed up all over the flooded flats. I have rarely, if ever, seen such an array of white ants' nests.

Our courses along the creek were north-east, north, north-west, and again north, and we camped at the Duck Pond Water-hole, which was just dry, as were other holes also. We sank a native well in the water-hole several feet deeper, but after expending much labour found the supply to be so small that it would hardly give water for our own needs, with none for the camels. Perhaps if made into a proper well, and timbered and sunk deeper, it might yield more water. On the 4th we travelled first north-east to where we crossed the Winnecke Creek on the way to Victoria river, and reached it in 6 miles from Duck Pond Water-hole. That water-hole was dry also, but some natives that we met on the creek piloted us to another, with a sheet of water 8o yards long, 15 and 20 yards wide, and 3 feet deep in the deepest part. This was, I think, the best holding hole we saw in Winnecke Creek, but it is not a permanent water.

From this hole we followed our outward pad right to Barrow Creek. In places the chain-track was almost obliterated by blowing sand. From water to water, where we had been piloted by black boys, I ran a prismatic compass traverse through the scrub, timing each run, and striking the through-bearing when plotted. In spite of every care the positions must be taken as approximate, for to get long-site shots is quite impossible, and there are no elevations to help one. However, all the waters set down on the map of my journey can now be found easily enough. The supplies in the wells could be greatly increased by sinking them a little deeper. My contract with the South Australian Government was to make trial wells, and the daily yield required was moo gallons. When that yield was obtained I had no cause to sink them deeper. They all yield well over the required quantity of excellent water.

We finished each well as we travelled back. In order to reduce the long stage between Cattle Swamp Well and Winnecke Creek we bored in a titree swamp 10 miles north-west of that well and obtained potable water at 9 feet 6 inches below the surface. It rose 2 feet 6 inches in the bore. We did not sink a well there, our provisions being at a low ebb. After we had replenished our food supplies at Barrow Creek we sank two wells (Baxter and Gettens wells) on the Hanson Creek, the positions of which may be seen on the map.

For the convenience of would-be travellers through that region I have set down the following particulars. Gettens Well is about 32 miles west-north-west of the Hanson Well on the Overland Telegraph Line. Baxter Well is 28 miles nearly due north of Gettens. These three are all on the Hanson Creek. The route then leaves the Hanson and in 28 miles on a bearing of 336.5° is Circle Well; then on 306.5° in 17 miles Fulge Well; in 21 miles on 298° Giant Well; on the same bearing in 6.5 miles End Well; on 352° in 13 miles Hit or Miss Well; on 327 in 32 miles Green Swamp Well; on 290° in 22 miles Cattle Swamp Well. The distance covered by these permanent waters is 199 miles. From the latter well to Merrenu (or Duck Pond) Water-hole on Winnecke Creek is 52 miles and the bearing is 316°. Merrenu to Ross Gap is 22 miles, direction a little north of west and follow the creek. From Ross Gap on 319° one will strike the eastern portion of Hooker Creek, then follow up the creek north of west, and in 1.5 miles past the big swamp is the Hooker Water-hole, the distance being 36 miles. Then on 340° in 27 miles is Catfish Yard and Waterhole on Victoria river. The distance from Cattle Swamp Well. is 129 miles. The waters are fairly safe for three months after the rainy season, but after that one can say nothing. From Hanson Well to Catfish Yard is 328 miles.

There is no immediate prospect of the completion of the North to South Railway, but in view of providing traffic to make the line payable the potentialities lying dormant for closer settlement in the large tracts of rich basalt soil of the Victoria river and adjoining districts should not be overlooked. If, instead of running the railway along the Overland Telegraph Line to Katherine it were taken off from it just north of Central Mount Stuart, and ran direct for Victoria river, and when nearing the river it followed along the eastern watershed, few, if any, serious engineering difficulties would be encountered right to the Katherine. The divergence would capture the trade of Victoria river and much of the Kimberley trade as well. It would also assist the development of all that rich country.

The object of the writer in compiling this account from very copious notes taken while the expedition was in progress is to place on record accurate information regarding a portion of the interior of Australia of which less is known probably than of any other part of the continent. Only by following the daily record of the journeys, I think, can anything like a correct idea of the country passed through be obtained, unless the route be travelled over. No generalized account could convey a correct impression of such unusual conditions. That the country is able to support a sparse native population we know, but to what useful purpose it can be turned for the benefit of stock-raisers, beyond affording facilities for shifting stock from place to place, is not yet apparent. The most unusual and most remarkable feature about it is, as has been pointed out, the existence of immense stores of water obtainable over very large areas from quite close to the surface. As the water is perfectly fresh and suitable for irrigation, it should be possible to turn the land to some useful account as is done in other arid countries. In addition to those hollows in which we obtained water so easily I am quite certain that there are a great many others that would yield equally copious supplies. Similar conditions obtain over a stretch of 150 miles, as proved by our line of wells. The width of the water-bearing area is unknown.

To my knowledge no surface indications of either coal or oil have been seen on the route we followed, but the shale and sandstone formation between Cattle Swamp Well and Victoria river is worth testing, and the Duck Pond on Winnecke Creek would be a good site to bore at. What lies below that great sand plain and sandhill area crossed by us is unknown. From End Well to north of Cattle Swamp Well no outcrops of consolidated rock were noted. A bore at a spot like Green Swamp Well put down to bedrock might afford valuable information. A vast depression apparently existed there in former times, which seems now to be nearly filled, but we know nothing of what lies below the surface sand.

Adieu Ridge and Scott Hills were the two most northerly points at which veins likely to carry valuable minerals were seen. At the latter quartz veins were much in evidence, but there was nothing of value in them. From these hills right to Victoria river along our route no outcrops of metamorphic or eruptive rocks were seen.

As regards the natives: they were never hostile, but of course ours would have been a strong party for them to tackle. We were well armed and they knew it. We gave them no cause whatever to be hostile, and any food we could spare we gave them. We tried to make them feel safe with us provided they left us alone, and in this we succeeded with all but those who lived far out in the sand-hill country. They were very suspicious and would hide themselves while we were travelling or when in camp. We owe much of our success to our own boys, and to natives who piloted us to waters in the country beyond where our boys had been. If we could have obtained the help of the wild natives no doubt they could have shown us many more waters, some of which must be surface waters, otherwise parrots, pigeons, doves, and cattle could not exist there.