Antarctic Summer

Getting There

Emerging from sleep, it takes some moments to place myself. I am not at home. The bed is adequate rather than comfortable and the tiny room lurches, rhythmically. I hear the notes of a clarinet, rising and falling, through the beat of wind and wave.

I should rise to investigate but the task is beyond me. A stupefying amalgam of exhaustion and seasickness keeps my head down. Swivelling and focussing my gaze I can make out the clarinet player on a chair sliding from corner to corner. The movement matches the music: Le Mere. I submit anew to the ravelling of sleep.

Looking from the deck of the Nella Dan, four days southwest of Melbourne, there are no icebergs yet, but the air is thick with frozen spray. Continuing from the regimen of cold showers, I am dressed in shorts and t-shirt. The wind is friend as well as foe, preparing mind and body for the adventure ahead.

After lifeboat drill, John Manning, who has made this voyage many times before, shows me the plot of the ship's progress. He checks it daily, revising his plan of the direction to row, should the ship founder.

Two weeks of life on board ship is a mixture of boredom and anticipation. Most passengers complain about the meals. Especially a dish of diced raw potato, which is taken back to the galley untouched, only to return for the next meal, and the next, and the next.

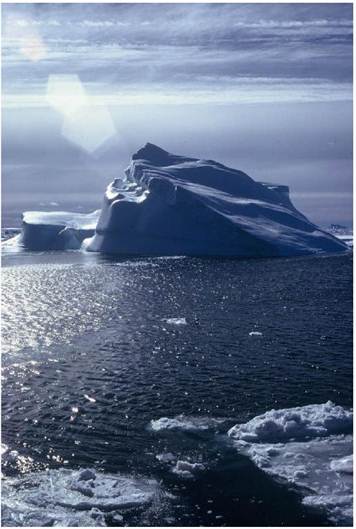

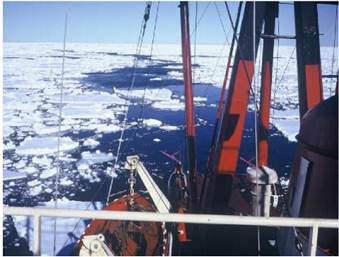

Turns at counting birds and a depth-sounder duty roster begin as the white continent approaches. The first iceberg is sighted and everyone debates camera f-stop, instead of just looking in wonder. Before long we are in bergy-bits and the fast-ice is near.

By chance, it is New Year's Eve when we tie up against the fast-ice, some thirty kilometres from the Antarctic continent. The man in the crane is blissfully unaware of the coming of midnight and of everyone, except myself, letting go their rope to run inside and welcome 1974. And so the unloading of the Pilatus Porter fixed-wing aircraft continues with just my faint efforts to stop it striking the ship's side. It gets safely on to the ice and we descend to bolt on the wings.

Mawson base consists of about twenty buildings of varying age, size, purpose and construction at the edge of a rocky bay, filled with fast-ice. The Porter has landed beyond the headland and I carry equipment over, past the line of huskies waiting for a sledge trip. A few foolish penguins venture here and one meets a savage end at the dog line.

Southern Prince Charles Mountains Survey

After travelling on the Nella Dan from Melbourne, I had arrived in early January 1974 at Mawson base. It is with relief, after two days of confusion and anticipation, that I climb aboard the Porter to fly a couple of hundred kilometres inland to Mount Cresswell in the Southern Prince Charles Mountains. The first leg to refuel at Moore Pyramid camp is uneventful but then low cloud covers our flight-path.

Carrying no electronic positioning equipment, and with the south magnetic pole so near, blind navigation is hazardous. It is then, I really start appreciating the pilot: Driver, first name Errol (as in Flynn), with "Bus" on his helmet.

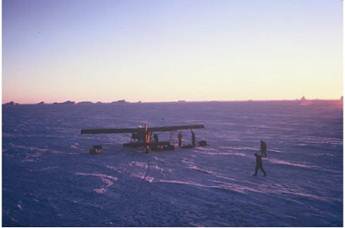

Spiralling down through the thick cloud we thankfully find Mt Cresswell, before it finds us, and land. Our base camp for the summer fieldwork is a neat row of conical orange sleeping tents, kitchen and communications caravans, large mess tent and a fuel dump, all hauled here by last winter's expeditioners.

From there I and an assistant fly to our first mountain to start extending the geodetic survey network and measuring the rate of flow of the Lambert Glacier. The work also involves astronomic observations, in the old style - calculations by hand from the Star Almanac, setting stop watches from a faint time signal and star observations at the theodolite that sometimes last all day and night. Not that there is night, that far South in Summer, so stars can not be located by eye and only the brightest can be seen in the theodolite telescope. Time is structured around observation schedules, radio skeds and helicopter movements.

We measure horizontal and vertical angles by Wild T3 theodolite and distances, electronically with a "Tellurometer", between rock cairns on top of mountains. We also measure the position of canes, placed in the ice in a semicircle a couple of hundred kilometres wide, two years before, to determine how far they had moved and hence allow glaciologists to estimate the amount of ice flowing into the Lambert Glacier and down to the sea.

Finding these canes required the invention of a new technique. I calculated the bearing and distance from my location on top of a mountain to each cane on the ice field. To find the 2 cm wide, 2 m tall cane I asked the helicopter to approach from behind me flying at constant speed, on the required bearing, and started my stopwatch as it passed overhead. After finding the rapidly departing helicopter in my theodolite telescope, I radioed corrections to its direction until it was heading straight for the distant cane. When the correct time had elapsed I asked the pilot to look for the cane. Amazingly all twelve canes were found, although some were over 70 km from the mountains. On only one occasion, when I was looking directly into the sun, did the helicopter need to land and check its location before finding the cane.

Standing on the top of Seavers Nunatak I compare this current project with recent fieldwork in the Western Australian desert. We are using the same helicopters, same survey equipment and at least some of the measurement techniques are equivalent. Building a rock cairn makes you thirsty, even in the cold. The differences are more subtle. The Australian desert is relatively benign; provided you follow some simple rules, it is hard to die. But already it is clear that the Antarctic is an entirely different kettle of fish; one false step could easily result in injury or death. This means that there is always a background sense of danger, of a need for caution, to watch your step.

One day early in our stay at Seavers our astronomical observations were interrupted by the surprise arrival of a Russian biplane. We knew that the Russians had field parties in our sector but never expected to meet one. The crew obviously didn't see our camp on the summit and the plane landed near the end of the nunatak and a few men alighted and walked off to look at rocks. We ran down the hillside and approached the aircraft. You can imagine how surprised the two men inside were when we knocked on the door. We couldn't speak Russian and they had no English so we just smiled a lot and shook hands. We must have looked hungry because as we climbed back up the hill our arms were loaded with tins of meat and milk and what turned out to be the most disgusting sweet biscuits I've ever eaten.

After about a fortnight of surveying from small nunataks and high mountains, the helicopters arrived to move my party to Burke Ridge. I had a new assistant who had lately spent time at Mt. Cresswell camp and brought stories of several aircraft 'incidents' involving one of the pilots. To reassured him, I decided that I would fly in that pilot's helicopter to lead onto the ridge, and he could follow with the other pilot.

We took off from Mt Newton early in the afternoon, circled the survey mark and took aerial photographs before heading South towards Burke Ridge, located at 65 degrees 25 minutes East longitude; 74 degrees 40 minutes South latitude.

I was always apprehensive of helicopter travel. As the fixed-wing aircraft pilot said: "Helicopters don't really fly, they just defy gravity". But my overwhelming feeling was of awe as I looked down on the towering mountainside of rock and ice. Burke Ridge was an exciting destination, viewed by previous expeditions but never occupied and this was my chance to get measurements to link the most southern rocky ridge into our growing geodetic survey network. To put it accurately on the map.

We came to the ridge, thin and steep, running roughly North-South, and assessed the prospects for a landing near the summit. We circled and I took off my helmet to take aerial photographs. There was a snow patch about five metres wide near the summit which looked like a possible landing site, but the wind howling in from the South-West made the helicopter buck. I turned to the pilot and said: "If its too hard to land I'm happy to carry the gear up the hill". He shook his head and banked the helicopter for an approach into the wind. I put my helmet back on and tightened the strap.

When we were about ten metres from the ground, the wind streaming over the ridge pushed the tail of the helicopter making it veer violently off line and to quickly lose altitude. Instead of powering forward into the wind, the pilot chose to turn the machine to the right to try to move away from the ridge.

The helicopter skid just caught the rocky edge and the machine somersaulted over the western face of the ridge. Death seemed inevitable as the tail and main rotors broke free and the engine screamed. The noise was horrific as our world tumbled down but I thought "you never know your luck", placed my left arm across my face and huddled down. The few seconds more of descent seemed like minutes as the helicopter continued to disintegrate and metal struck my helmet and left arm. Then all was still, the helicopter stuck in a rock outcrop and me hanging from my seat belt. I released the belt, climbed from the shattered bubble, and pulled the pilot out. We ran as fast as we could across the rocky hillside till about fifty metres from the remains of the helicopter. I expected it to explode as the load included several car batteries and plastic containers of fuel but it just sat there crumpled among the rocks and snow and hissed.

The pilot pulled the emergency radio from his trouser leg pocket and called the other helicopter, hovering high overhead, saying that the wind conditions were terrible, not to try to land and to radio for help. The pilot of the other Helicopter later told me that he was so overcome by watching us crash that he would have been incapable of landing to pick us up.

I thought my left arm was broken, as I couldn’t move it, so I tied it inside my coat and started searching the hillside for parts of the load that had spilled from the helicopter as it bounced and broke up. I was elated to find my field books with the records of the past fortnight's observations. Next I located the survey equipment. The tellurometer was smashed but the sturdy theodolite was still in its cast iron case, although the base was cracked. However, I could see where a bolt from the exploding engine had pierced the case, left its hexagonal impression on the telescope focussing barrel and ricocheted away, rendering the theodolite inoperative.

The pilot called me over. Manning, the survey party leader, waiting on Wilson Bluff for the measurements had heard the emergency message and was calling me on the radio. He barked three rapid-fire questions: Is anyone dead? Are you badly hurt? Can we still get the measurement?" I answered no to each. By this stage I was feeling a lot safer but very weak so I settled myself among the rocks to await developments.

The Porter fixed-wing aircraft had been taking aerial photographs about a hundred kilometres away when the pilot heard the emergency message. He quickly returned to Mt. Cresswell camp, refuelled, took on board the expedition doctor who happened to be there, and flew towards us. When we saw the Porter circling the ridge, looking for an area of ice without crevasses to land, we climbed down the rest of the hillside.

As we reached the ice we saw the Porter coming towards us on its skids. It stopped about thirty metres away and the pilot jumped from the cockpit and ran towards me opening a can of beer. "Here, get this into you" he said. Declining, I turned instead to the doctor and a syringe of morphine. The four hour flight back to Mawson and the trek down from the airstrip were mostly a blur for me and it was not until I was safely inside the small medical room at the base that I could relax. I was safe and all my defence mechanisms collapsed. I vomited and wept.

My arm was not broken but I was stuck at Mawson base for four days due to bad weather before I could return to Mt Cresswell camp to resume the survey work. I then spent a couple of days at the camp doing astronomical observations with Manning. We observed all through the night and, although my left arm was still immobilised, he insisted that I do all the observations at the theodolite, while he wrote down the readings I called out. You see, his job was the more static and hence much colder one.

Soon I was flying onto a mountain near Mount Cresswell with another helicopter pilot. He saw the naked fear in my eyes, put a hand on my leg, smiled broadly and said "I'm not like that other bloke - relax". And I did.

Surveying West of Mawson

We were not able to do much more work in the Southern Prince Charles Mountains, with the loss of the helicopter, and within a few days returned to Mawson. We then headed off again to survey a set of islands near the coast to the West. The first night on Havstein Island I was in for a surprise - it got dark! Now that it was February, and having moved so far North, the days of continual daylight were past. We eventually found torches and candles to cook the evening meal by.

As with our other camp sites, we were eating from 1960s ration packs. The main food was a 10 cm bar of compressed precooked meat and vegetables, with the exotic name of "HF6". We would whittle chunks of this bar into a pot, add some ice, then heat it over a small kerosene stove. To the mushy stew we usually added pieces of thick wheaten "sledge biscuits". Fortunately there was also some chocolate and honey, but the staple was HF6.

The survey work was interrupted by bad weather but we eventually completed the coastal survey loop and were ready to move inland to finish off a traverse started years earlier. A blizzard was on the way and our helicopter pilot just had time to pick us up from Alphard Island, drop us at Fram Peak, then return to Mawson.

Even if I hadn't crashed on Burke Ridge four weeks earlier, I would have been very nervous flying onto Fram Peak, with its hundreds of metres of rock and ice cliffs and small pyramid shaped summit. Arriving, we soon realised that there was not enough flat ground to land on the summit and not sufficient time before the blizzard to be dropped off lower down and carry our gear to a safe camp site. So the helicopter hovered near the ground, we threw out the gear and jumped. Crouching low to avoid the rotor blades we pulled our gear into a heap and waved farewell to the pilot as he circled then headed off for Mawson.

Assisting me on this trip was a young geologist who fortunately had mountaineering experience. He quickly dismissed the idea of camping on the only small flat area, about ten metres down from the summit, as it was too exposed to the wind, and climbed around to the lee side of the mountain top. Here was a huge bulge of ice hanging uninvitingly over a vast cliff, not my idea of a camp site. But he convinced me it was stuck firmly onto the rocks and we quickly started carving out a flat bench in the ice large enough for us to pitch the tent. After this was set up we got the charging motor going to top up our batteries and radioed to Mawson our situation report, as the blizzard set in.

All next day the blizzard raged. The sound was horrendous as the tent heaved and strained. The radio aerial wire must have been torn away and we were out of communication. We snuggled into our sleeping bags and cooked some HF6 stew. My companion thought that he could extract the last of the honey from its tin by heating it on the stove, only to have it explode and coat the inside of the tent with a very thin layer of the last of our sweetness. My diary entry: "This is not, repeat NOT, the life!".

Then all was confusion. The tent was ripping and I grabbed the fraying edges, pulled them together and tied them off with a boot lace. Clearly we had to do something fast. Rushing outside we were faced with whiteout and howling wind but managed with the spade to cut blocks of ice and heap them on the edge of the tent to stop it blowing away. Crawling back into its much reduced interior we reviewed our situation and decided that the tent couldn't be trusted and an ice cave was needed.

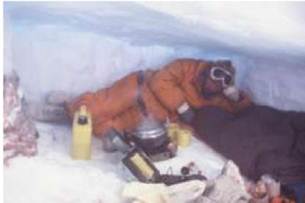

Although we were in the lee of the summit the wind was relentless. They told us later it exceeded 150 knots at Mawson. So we knelt in the snow and hacked into the hillside with an icepick and spade. This allowed us to open up a deep cave in the ice reaching back until we hit rock. We then cut blocks of ice to form the front wall and a square entrance tunnel. A couple of hours later we were feeling a lot safer huddled into a two by three metre split level ice cave, complete with feature rock wall. Having transferred our sleeping bags, food and radio into the cave we knew we were able to last out at least a few days of blizzard in reasonable comfort.

Next day the blizzard subsided and we could erect the observation text over the survey mark on the summit and get the radio going again. Before long there was a message from Manning. He just had enough time to get to Mt Cook before the weather was due to worsen again and wanted to get a measurement from there to Fram Peak. He had managed to contact the other survey party on Baillieu Peak, who had fared little better than us in the blizzard, but they were ready to measure a distance to us and to shine a light as a target for us to measure the horizontal angle between them and Manning at Mt Cook.

We measured the two distances at record speed, though with some difficulty as the tellurometer signal penetrated weakly through the thick drifting ice. Manning was obviously doing it tough on Mt Cook as the weather closed in and finally had to abandon the light, leaving it shining to us to finish the angle while he flew off to Mawson. We completed the measurements as the wind howled in again, packed up our equipment and retreated to the ice cave. We were very pleased to hear on the radio that Manning was safely back at Mawson, where the Nella Dan had just arrived in the now ice-free harbour.

The blizzard lasted another two days, during which we managed to finish our survey work on the summit and carry most of our gear halfway down the mountain. The next morning in much better weather we carried our tent and remaining gear down the mountain to meet the helicopter which flew us to Mawson. Arriving there I felt great relief to be safe again and very pleased that we were able to finish the survey despite the weather. This had allowed us to complete the traverse commenced in the summer of 1964/65 ten years before.

We spent a couple of days at Mawson unloading next year's supplies from the Nella Dan. Then we sailed around the coast to establish a fuel dump for operations next summer, before heading to Davis base.

Unfortunately, the harbour there was still full of ice so no

supplies could be landed. However, we surveyors had a grand time doing some

survey measurements nearby, visiting the elephant seals and meeting the blokes

living at the base. After two days we sailed for Melbourne and home.

by Andrew Turk, 2011