Report on Journey to Amery Ice Shelf

October 1962 – January 1963

Personnel

Peter A. Trost

Mark McD. Single Tractor Party

Noel E. Foley

M. John Freeman

Ross L. Harvey Dog Party

Kevin Walker

Purpose

This journey was organised to locate and prove a route to the Amery Ice Shelf from Mawson, with a view to carrying out an intensive glaciological program in future years, involving the use of heavy equipment including an ice drill.

Very little was known of this Ice Shelf and there was even considerable doubt as to whether it would be possible to approach the Shelf and drive vehicles on to it.

For this trip we aimed at achieving the following work :

A. Glaciological studies along the whole route to as far south as possible on the Ice Shelf.

B. Meteorology Observations.

C. Barometric Heighting of the terrain traversed.

D. Mapping control by astrofix where the opportunity presented itself.

E. Collection of Geology and Lichen Samples if applicable.

Tractor party outbound at GWAMM in October 1962 from L to R: Peter Trost, Mark Single, John Freeman, David Carstens and Ted Foley.

Method

Transport was by Tractor Train and Dog Teams. The tractor train consisted of two D4 Caterpillar tractors towing supply sledges and two caravans (living), one large and one small. Two dog teams were used with seven dogs in each team. A single Snow Trac was included (No. 1) as scout car and was used as forward vehicle for the barometric heighting. It was also used for reconnaissance and survey work on the Ice Shelf.

The tractor train was used to land men, supplies, dogs, etcetera onto the Ice Shelf as far south as possible. At this point a depot was set up, that is Depot E nicknamed Eldoodmur. At this depot the dog team separated from the tractor trains and worked their way south on Glaciology studies. In the Snow Trac, a party of three, Single, Trost and Self, headed towards the western edge of the Ice Shelf on a general survey; Foley and Freeman remained at Depot E to carry out meteorology and operate as a radio station.

Outbound tractor train at GWAMM in October 1962.

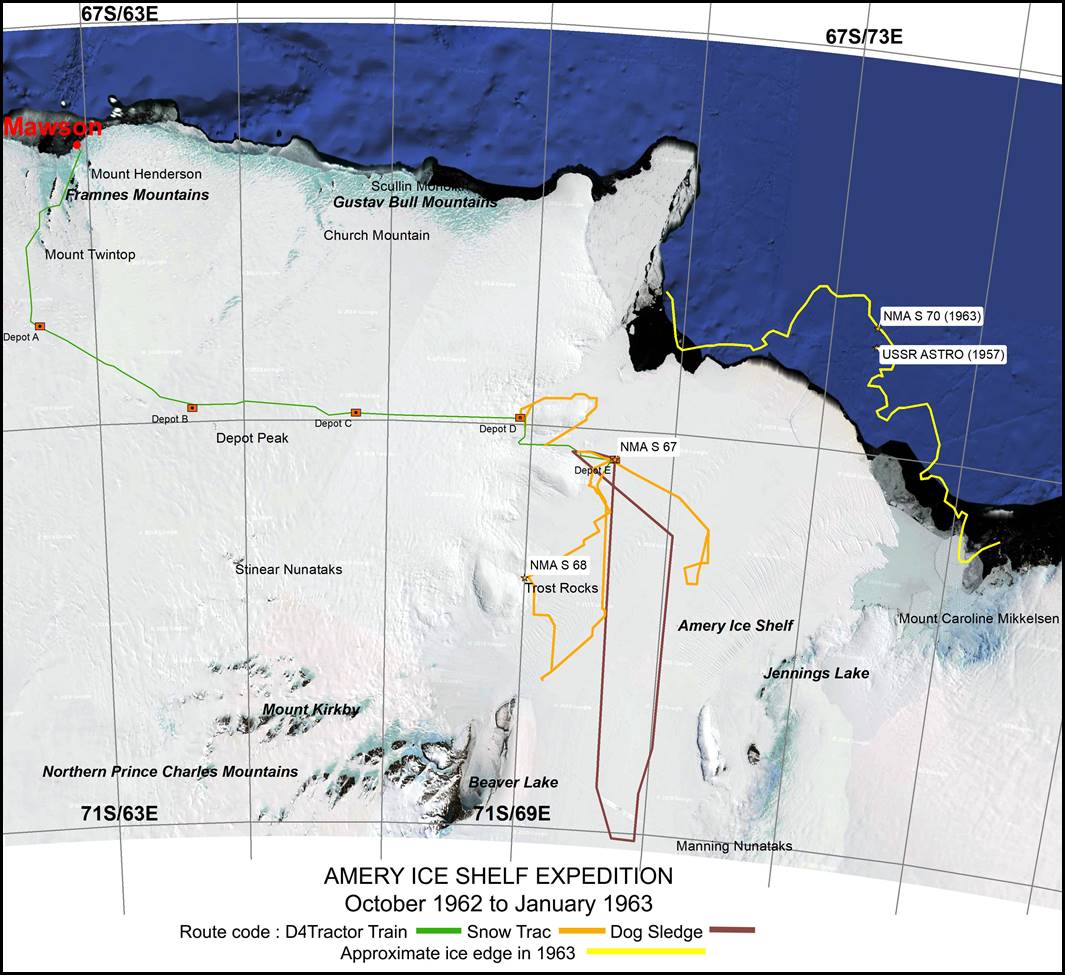

Track of 1962-63 Amery Ice Shelf field party. (Prepared by Paul Wise 2018.)

Track

The details of courses and distances and track markings are set out in an appendix to this report [This appendix NOT included here. The track of 1962-63 Amery Ice Shelf field party is depicted on the above map. David Carstens’ 1:500,000 scale Route Map of the 1962 Amery Ice Shelf Journey can be accessed at this link.

For the first 138 miles from Mawson the journey followed the route used since 1957 with the addition of the section from Depot A to Depot B as traversed by the Autumn Depot Laying Journey 1962. This is the route through Hordern Gap and west of Twintop. Depot A and Depot B were laid by the Autumn Journey in positions 68° 30’ S, 62° 09’ E, and 68° 55’ S, 64° 17’ E, respectively.

From Depot B onwards we were in new country. We found we were able to keep an almost constant easterly course. The only major deviation was near our outward Camp 11 at 68° 54’ S, 65° 50’ E, where crevassing was detected. We descended one steep slope and then a second ridge was ahead, the eastern slope of which was crevassed. The crevassing in this ridge increased towards the north, and further to the north, at a distance of 3‑5 miles, badly crevassed domes were visible. By heading S E for four miles this area was easily cleared and the country flattened out again.

The country is continually undulating, like rolling downs; on the uphill grades trouble was often had with bogging of the tractors. This occurred when large sastrugi or snow dunes had to be climbed as well as the normal slope of the terrain. By carefully picking the way around the largest of these obstacles, the number of boggings was minimised.

The usual remedy for getting out of a bog was to unhitch the tractor, pull forward over the sastrugi, and haul the sledges through on a wire rope. For the whole journey east the sastrugi was almost at right-angles to our course, which was a most uncomfortable angle, and great care had to be taken driving both the Snow Trac and the D4s.

Outbound tractor train hitched-up for heavy going at Hordern’s Gap.

From Depot C the terrain started to fall rapidly; here the sastrugi became less, but the surface became softer. The sledges were furrowing to the depth of the runners in places and the turntables on the articulated sledges would drag, causing much heavier pulling. On the outward journey this did not cause much holdup because of the downgrade. Coming home, although more lightly loaded, this soft snow caused a great deal of trouble, mainly because the tractors could get no traction.

There appeared to be crevassing to our north most of the way which indicates a most fortunate choice of route.

Journey Out

The brief daily diary appended covers the progress of our outward journey [NOT included here].

Use was made of the Depots A and B for restocking the fuel supply. We were towing a particularly heavy load and our fuel consumption was higher than expected on the outward journey. To save weight we had earlier offloaded some of the emergency reserve fuel it had been planned to carry.

The food at A and B was not required. This was restacked and suitably marked with finders on the return journey.

Progressing further we established a depot of fuel at position 68° 57’ S, 66° 22’ E, Depot C and another at 68° 58’ S, 68° 53 E, Depot D. At Depot D we also left two light steel sledges and as much of the food as was reasonable to leave behind.

Dog Food and Sledging Rations were also left at the depots for the dog party who were to return independently along this track.

Depot D was at the base or landward end of a large ice dome peninsular, and it was from here we had planned on making our approach to the Shelf. Our altimeter showed we were still about 900 feet above the Shelf with only a matter of about 5 miles in which to descend. The tractor train was parked at the depot whilst two reconnaissance parties set out to inspect the approaches. (Subsequent height determination shows that Depot D was at 1000 feet elevation and the Shelf adjacent 430 feet, a descent of 570 feet).

The Southern Party, Ian Landon-Smith, Ross Harvey and Mumbles (Kevin) Walker with the dog teams, set out south and Peter Trost, Mark Single and Self, headed to the north in the Snow Trac.

In the Snow Trac we completely circumnavigated the peninsular to meet up with the dog party on the southern side. They had located a sound route onto the Shelf, although quite steep. They had travelled 10 miles along the Shelf and found no crevassing.

In the Snow Trac we had found the approach to the Shelf on the other side of the peninsular was not very steep, but that once on the Shelf there was a great deal of crevassing.

While the dog party waited at their campsite in the bay on the Ice Shelf, the Snow Trac returned to Depot D via the doggers track and it was decided the tractors be brought down via the steep slopes and onto the Ice Shelf. This was accomplished with no trouble at all.

Our reconnaissance journeys indicated that the mapping of the Ice Shelf edge in this region is not entirely correct. The shape of the peninsular is correct but it should be 5 miles further south on the map.

The surface on the Shelf was soft snow, but with the light loads and the fact that there were no hills, good progress was made. For the first twenty miles on the Ice Shelf, mainly in the bay, no trouble from crevassing was experienced. The Snow Trac was leading and picking the way and did locate some large crevassing to the south of the track taken, but this was easily avoided. At 69° 05’ S, 69° 45 E, was a large dome in the Ice Shelf, which was badly crevassed on the top. A track past this was selected in the Snow Trac but as the D4s followed two crevasses opened up under the leading D4.

The second D4 was able to pick a safe bridge to cross and no further hold up was had. The crevasses that opened up were about 3 to 4 feet wide and did not disable the tractor which clambered through, bringing the sledges over safely, also.

At Camp 17 a stop was made to carry out a careful reconnaissance by Snow Trac as crevassing was becoming more in evidence. The track chosen was to the east. Several crevasses were found but were considered to be well bridged. The D4s were brought over this section and where the crevasses were in evidence, careful probing by crow bar was used to prove the bridges before crossing. We did not have any part of a crevasse drop out in the crossing points so chosen.

At the end of this section of track, eleven miles East of Camp 17, we set up Depot E (Eldoodmur). The track details for here are given in the navigation table in the appendix [NOT included here]. The table gives the track which avoids the crevasses whose bridges had dropped out under the tractors. (That is, the track used on the way home). The last eleven miles however would need extreme care by any future party. The area is quite safe for travel and is a practical route provided the crevassing is seen and avoided. This does mean keeping a good lookout and probably having a careful reconnaissance by Snow Trac; it is good safe Snow Trac country.

Work on the Ice Shelf

The dog journey and the glaciology carried out are covered in a separate report by Ian Landon-Smith.

The work carried out by Snow Trac I will include here.

Of prime importance was the meteorology carried out at this base on the Ice Shelf, Depot E (69° 09’ S, 70° 09’ E.). Three weeks of observations were obtained. Ted Foley kept up three‑hourly observations, with the help of John Freeman, for the whole time, as well as twice daily balloon flights.

Not one observation was missed. The results were transmitted to Mawson on twice daily scheds.

The weather on the Ice Shelf was particularly mild by Mawson standards. The main feature is the lack of wind. The meteorological results will show the picture more clearly.

The caravans at the depot also handled the radio traffic for the two parties travelling on the Ice Shelf.

Snow Trac Reconnaissance

After five days at Depot E, mainly held up by whiteout conditions, the Snow Trac left the depot to carry out an inspection of conditions along the west coast of the Ice Shelf and to consider the mapping of this region. More crevassing than was bargained for was encountered. On the basis of our easy access to Depot E it was expected that the Snow Trac would have little trouble travelling to the coast line and then along it. Travelling south – west, the way was blocked after 7.5 miles by severe crevassing. The track taken to avoid the worst crevassing and try to make our way to the coastline, is shown on the attached sketch map. The Snow Trac is an excellent vehicle in this bad country. Many times the vehicle collapsed through snow bridges of crevasses but crawled out onto solid ground. Mostly the crevassing was evident from indications on the surface and by crossing at a suitable angle, preferably between 45 and 90°, the Snow Trac handled the openings even when quite large bridges dropped out.

Considering the nature of the country, looking back, it is quite remarkable that we had so little trouble. In all, we were disabled three times by crevasses. In each case the Snow Trac broke through the bridge of a crevasse longitudinally. On these three occasions there was no visible sign on the surface, although there were other crevasses in the area.

The Snow Trac was recovered using its own winch and a hand winch. The shortest recovery took half an hour; the longest – out of a 4-foot wide crevasse – five and a half hours.

Snow Trac recovery from crevasse on Amery Ice Shelf in December 1962;

Mark Single (left) and Peter Trost.

Our experience in this very broken country indicated that it was safer to be driving in the Snow Trac than to be walking around. In one area the Snow Trac broke open about twenty crevasse bridges in about half a mile. To pick our way out of this region we travelled on foot, roped together, and continually put our foot through bridges. The crevassing was very broken and followed no pattern.

Generally a definite pattern of parallel crevassing was observed and the crevasses ran at a remarkably constant direction. In every region of crevasses along this shoreline we measured the crevasses as running 150°–330° True. On one occasion we ran parallel to a large crevasse on a heading of 150° True for eight miles.

Eventually, when we had cleared the worst of this crevassing, it was possible to make our way coastwards, a prominent dark mark on the edge of the plateau was selected as a steering mark from about 20 miles out. As we approached closer this was recognised as a rock feature. We made our way to it and set up camp. The position was 69° 46’ S, 69° 01’ E. We spent three days here doing an astrofix, collecting geology samples and lichens.

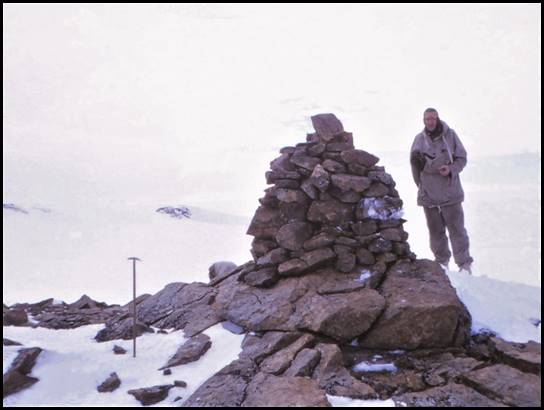

At Trost Rocks on western side of Amery Ice Shelf in December 1962;

Peter Trost (left) and David Carstens. Photo taken by Mark Single.

Peter Trost at cairn erected on top of Trost Rocks in December 1962.

After leaving this point we continued further south to as far as our petrol supply would allow. We were unable to make a further landfall although we were within 10 miles of Jetty Peninsular. Crevassing and shortage of petrol forced us to turn about and return to Depot E.

We returned by a route further to the East than our Southern leg. Although we crossed many large crevasses, the bridges were more solid and we covered the eighty miles in a day, including five and a half hours extracting the Snow Trac from one crevasse which we did not see.

After our return to Depot E it was proposed to do a run to the east and check, by surface travel, the region on the map shown as below sea level. As time was running short it was planned to make this a one day attempt. The day dawned cloudy and whiteout so the project had to be abandoned.

Then we had a message from the dog party to say that Ross was ill with a temperature of 102° (F). The next night on the radio sked we heard Ian call us and then we heard no further signal. We knew they were having trouble with the cord from the generator to the radio, but it was most disconcerting, at this stage, not to know how Ross was.

It was decided that we should go in the Snow Trac to the last known position of the Doggers, travelling along the track they were most likely to take. We carried repair gear for the wireless and medical supplies in case they were needed. We were unable to locate the dog party but eventually a radio message from Depot E told us they had arrived back there. So we returned immediately ourselves. On this trip we covered 140 miles in 24 hours, including the distance covered in a box search of the area of the Doggers last position. Ross had recovered after one day in bed and they had headed back to the Depot.

This trip took us near to the position of the low lying terrain but time did not permit a thorough investigation. We ran a barometric heighting program along our track, using the caravan as base station, and reading the altimeter in the Snow Trac at regular intervals.

Departing Depot E on Amery Ice Shelf late on 21 December 1962; from L to R: Mark Single, Peter Trost, Ross Harvey, John Freeman, David Carstens,

Ted Foley and Mumbles Walker. Photo taken by Ian Landon-Smith.

The Return Journey

The return journey was much quicker than the outward one. The old route was followed. Sometimes it was possible to follow tracks and sometimes it was necessary to steer on the astro compass. The barometric heighting was continued for the full distance as a close (a check).

Our main troubles were had from the point of leaving the Ice Shelf to about 17 miles west of Depot D. On this section soft snow and steep up-grades made it necessary to relay the trains. The worst section was the one where it was necessary to bring each articulated sledge separately to the top of the hill using two tractors. In all, four trips were necessary over this section. One of the most successful methods of keeping moving was to connect the whole train together and haul with both tractors. This increased the traction available, and if one tractor started to bog in soft snow, the other was still pulling.

After leaving Depot C, the sections between depots was covered in continuous runs – the longest, 62 miles, in 18 hours, including a breakdown of an articulated sledge.

From Depot B the tractor train party paid a visit to Depot Peak. We set out to follow the navigation of the 1955-56 parties and succeeded in locating two old route marker stakes and an empty fuel drum.

The drum and first stake were E18, the old depot site near Depot Peak. We found no sign of the depot stores. A little tentative digging was done near the stake and drum but nothing found. The second stake found was on the track taken by the 1956 party when parking the caravan for use as a Meteorological Station in 1957. We ran out this track but could not locate any more stakes, nor the caravan. Presumably the caravan is now buried.

We drove the Snow Trac onto the South-Eastern side of the Peak, almost to the top of the snow slope. John Freeman was the only climber among us, so no attempt was made on the highest point of the mountain. A collection of lichens was made, several varieties being located, although they were not very plentiful. Rock samples were also collected although this peak had been geologised professionally. The marker stakes found were measured for accumulation / ablation and the results handed to the Glaciologist.

From the Twintop depot it was proposed to do a trip 15 miles east to a group of Nunataks on which National Mapping had requested I do an astrofix. The tractor train was to be left at Twintops and the five of us journey by Snow Trac. We waited for two days for the weather to clear, but, just about the hour it did clear up, we had a message from the O.I.C., Mike Lucas, telling us that Frosty (Ken) McDonald and Bob Nelson had got involved with a crevasse, damaging their Snow Trac, and that they were both suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning. They were eight miles north of our position and had been coming to man a Met. Station at Twintops until changeover. We were asked to abandon the astrofix and rescue the Snow Trac and men, which we did. Fortunately both Frosty and Bob were well, although they had spent a cold night in the Snow Trac.

We all then returned to Mawson as our Snow Trac was the only serviceable vehicle belonging to Mawson and fourteen Russians had arrived. Their aircraft were parked eight miles from Mawson at the Rumdoodle airfield.

The rest of the trip was uneventful. We encountered very rough sastrugi near Hordern Gap. Over the whole return journey we noticed a marked change in surface conditions.

The heighting was terminated at the known height station at North Masson Range (Rumdoodle).

The descent of the last slope into Mawson was notable in that we had a tractor bog. Instead of the smooth glassy ice we were accustomed to, the surface was soft and crystalline, little trouble being experienced with the sledges slipping sideways.

The dog party had preceded us by three days. We travelled separately but close together until Depot B when they headed straight to Mawson.

Achievements

On this journey we have proved a route to the Ice Shelf which should be quite satisfactory for any future expeditions. A total of 750 miles of traverse was covered on the Ice Shelf, showing something of the pattern of crevasses and the nature of the Shelf in general.

In addition, observations of a scientific nature were recorded as follows: -

a. Glaciology. Fifty-five accumulation and ablation stakes were placed along the route and measured. A total of eighteen pit investigations were carried out. A strain grid was set out on the Ice Shelf and re-measured after three weeks. A movement line was placed near the south extremity of the Ice Shelf, and observations on surface density and conditions were recorded.

b. Survey. Two astrofixes were completed, one at Depot E to determine movement of the Ice Shelf, a suitable beacon being erected for a repetition of an astrofix in a few years time; the second for mapping purposes on the rock feature encountered at 69° 46’ S, 69° 01’ E.

c. Meteorology. From Mount Twintops onwards six hourly met. Observations were maintained and the results transmitted to Mawson on twice daily radio skeds. Balloon flights were carried out at Depot B and Depot D when time and weather permitted. At Depot E the base was run as a met station for three weeks, sending to Mawson three hourly synops and twice daily pilot balloon flights when the weather was suitable and taking into account the limited amount of hydrogen available.

d. Lichens. Lichens were collected on the rock feature at 69° 46’ S, 69° 01’ E, and at Depot Peak on the return journey. The growth was prolific on the Ice Shelf feature but sparse on Depot Peak. These were the only rock areas visited. The collection has been handed to Rex Filson, lichenologist in a voluntary capacity on the Station. (His records being available through ANARE Head Office).

e. Geology. Country rock samples as requested by Trail and McLeod of Buromin, Melbourne, were collected and passed to the care of John Branson at Mawson, for return to his Department, Buromin.

f. Heighting. Barometric Heighting by modified leapfrog method, using radio communication, was carried out on the outward and return journey.

g. Bird Log. Ted Foley kept a log of birds sighted and relevant details during the trip. The log was handed to the station Biologist, (Medical Officer) Dr Wigg for safe keeping.

Concluding Remarks

Navigation

Navigation was done from the leading vehicle, the Snow Trac, using the astro compass for heading. A cyclometer sledge wheel was used for mileage as the Snow Trac speedometer does not record tenths and gave somewhat high distances. The cyclometer used was for a 28-inch wheel and was used on a smaller wheel, so a correction factor of 0.8 was applied. A position fix was obtained, by theodolite observation, at each depot except Depot A.

Heighting

Once the system was understood by all members and the radio procedure was perfected, the heighting work proceeded smoothly. Generally the Snow Trac travelled 5 miles ahead as the forward heighting station. It was important to leave a suitable identification mark at a height station to avoid confusion with other route markers. Normally the numbered ablation stakes were used. No effort was made to maintain exact five mile intervals.

Vehicles

I consider the arrangement of our vehicles was ideal, two D4s and a Snow Trac. Mechanical problems are dealt with in the Engineers report; but generally it was a trouble free journey mechanically.

Sledges

The sledges did cause some troubles. The Nansen and Light Steel sledges tended to accumulate snowdrift around them more than any others and were difficult to dislodge after being parked for a period. Also they did not track with the articulated sledges. The light steel sledge dragged in the middle because of its low ground clearance. This was a problem in soft snow. The articulated sledges work very well but the four cross members over the front turntable of one were snapped from the chassis by the continual buffeting whilst striving to get moving each time in soft snow. The second fault which developed in an articulated sledge was the central holding pin for the pivot on the front turntable of the caravan sledge dropped out. This was noticed when the caravan began to rock alarmingly.

Caravans

The Freighter caravan was very comfortable to live in and made life no more arduous than at Mawson. However it is definitely recommended that the use of a lighter caravan, similar to The Pid would be a great advantage in soft snow. A small caravan used as living quarters and a tent used for sleeping should be comfortable accommodation for five people. The heavy caravan was a definite hold-up for our ascent back onto the plateau.

Radio

The AN/GRC-9 gave excellent service throughout. Contact with Mawson was quite adequate during the journey and the radio telephone link for heighting functioned well. On the return journey the power supply from the Snow Trac battery failed and the set was operated on the hand generator.

A rhombic aerial was prefabricated at Mawson to be erected on 15 foot poles and to be beamed at Mawson from Depot E. This aerial was erected at Depot D and tested. Little significant gain was achieved and it was found that a doublet, which is more simple to erect, gave very satisfactory results.

Route Marking

The route is marked by a series of numbered ablation / accumulation stakes with black flags attached. Also fuel drums were punctured and placed when available. Details are in the Navigation Table in the appendix to this report [NOT included here].

Crevassing

Crevassing on the Ice Shelf is of a different nature to that on the plateau and a few observations here from a route finding point of view may be of help.

The crevasses that can be seen on the Shelf are usually indicated by an extremely broad sunken bridge. These vary from 10 feet to 100 feet in width. The bridges were usually very thick and only showed openings at one side. However on several occasions we saw places where the bridge had collapsed en masse for a length of two hundred feet and up to forty feet wide. These collapsed bridges, or the resulting hole, cause a wind pattern which deposits a snow dune on the down wind side of the hole. A badly crevassed area is indicated by these huge hummocks, some of them twenty feet high. They have the shape of a whale.

We referred to these crevasses as canal slots because they were so long and straight and looked so much like an irrigation canal.

Not all the crevassing was as easily seen as this. Large rifts occur in quite flat areas with hardly a hummock in sight. Sometimes a section of sunken bridge can be seen but mostly the build up of soft snow conceals the indications. Six inch openings on the surface mostly indicate a crevasse six feet wide below. These are usually well bridged, if not right where the crack appears on the surface, the bridge is probably good within one hundred yards.

Similar to on the plateau, wherever a sharp rise or dome occurs the crevassing is very bad.

The majority of the country covered in the Southern Snow Trac traverse would be highly dangerous for D4 travel; but on the eastern run from Depot E, although we crossed a region of crevassing about five miles wide immediately east of the depot, I am sure a safe route for the tractors could be located.

The three crevasses in which the Snow Trac was caught showed no sign on the surface. We did not travel on any day of doubtful visibility. That no indication was visible is shown by the following incident. On the third occasion that the Snow Trac went down, Mark got out to consider the situation and walked round to the front of the vehicle, stepping carefully where he thought the opening to be, only to crash through the particularly thin bridge to remain clinging to the brink of the crevasse with his hands on one edge and his feet braced on the other side.

Snow Trac for Seismic Work

I would like to use this report to record a suggestion discussed while we were travelling on the Shelf. We feel that in view of the surface conditions on the Shelf, that a highly mobile drilling outfit could be hauled by Snow Tracs and supported by a tractor train. This may be the most satisfactory way of working on the Ice Shelf. There can be no doubt that the Snow Trac will cross most of the crevasses on the Ice Shelf safely, and even if it does break into a crevasse it is readily recovered.

Previous Experience

We, who were on this journey, realise that our results were made possible by pooling the experience of all previous parties in field travel. For their instruction, both by report and verbally, we are most grateful. It is to be regretted that full appreciation of what has previously been learned, is not achieved until the same set of circumstances presents itself.

Finis

I would like to express my appreciation to all concerned in this journey and its preparation, for the cooperation received. To Mike Lucas, O.I.C., a special thank you for typing this report, (the original and carbon copies), the report of a journey which he had hoped to make personally, but from which he was precluded by ill-health.

1st February, 1963. (D.R.Carstens).

Retyped by D. R. Carstens, November 2002. (Computer file ANARE Amery Ice Shelf 62-63)

Footnotes and Postscripts.

The retyping of this report has copied the wording, the format, punctuation and content except in a few of occasions where some variations to words or abbreviations clarified the meaning. Minor correction and addition is included from reference to the original hand written report. This cross check resulted in some improvements in the hand written report. Some additional punctuation has been added in the belief that this improved the readability of the text. [Further minor edits were made in 2018 and Appendix A and Appendix B added.]

Temptation to add explanations in some places was resisted. Where it was considered an advantage some additional comment is inserted in brackets.

The distance travelled by the tractor trains is not mentioned in the report. It can be derived from the Navigation Table but travel by category is recorded here.

Tractors 600 (Statute) Miles each. Total out and back.

Snow Trac 750 (Statute) Miles All duties.

Dogs 620 (Statute) Miles On Shelf and return to Mawson.

Careful reduction of heighting results after return to Australia showed some interesting results. During 1962, available mapping showed heights on the Ice Shelf, derived by radar altimeter in an aircraft, of about thirty metres. The 1962 barometric heighting from Mawson showed sixty metres, that is, higher by thirty metres.

In 1968 levelling from the front of the Ice Shelf, using optical survey instruments, confirmed the 1962 result. The area below sea level is not identified from 1962 or 1968 work.

Another interesting item is not included in the report but is contained in the field notes. This is the sighting of a mountain peak from Depot C on a bearing of 220° True. It was identified at the time from the map as Summers Peak. Even though the peak should have been below the horizon, the mountain was clearly visible. This had to be a case of abnormal refraction.

D.R.C.

Appendix A

Journey to Amery Ice Shelf

October 1962 – January 1963

Survey and Navigation Equipment

|

Item |

Weight (lbs) |

|

Wild T2 theodolite |

17.5 |

|

Tripod for theodolite |

13 |

|

Theodolite carrying case (pyramid) |

17.5 |

|

Survey Camera (using theodolite tripod) |

12.5 |

|

Lighting Set |

9.5 |

|

Altimeters Two (7lbs each) |

14 |

|

Compass Prismatic Silver Circle |

2 |

|

100 ft Tape |

1.5 |

|

300 ft Tape |

3.5 |

|

Binoculars |

4 |

|

Astro Compass (Complete with box, box=2.5lbs) |

5 |

|

Star Drills |

- |

|

Deck Watch |

4 |

|

Marine Sextant (in Case) |

9.5 |

|

Black Glass |

2.5 |

|

Plumbobs |

2 |

|

Thermometer (lost) |

- |

|

Compass Prismatic, Oil Bath, Landing |

2 |

|

Levelling Staff |

9.5 |

|

Spring Balance |

- |

|

(Sub Total) |

129 |

|

Plus Nav Box & Contents |

30 |

|

(Total) |

159 |

Appendix B

Amery Ice Shelf – Order No. 2

|

Here is a check list of personal gear you are advised to take : |

|

PRIVATE |

|

Ventiles |

|

Shirts |

|

Pyjama trousers |

|

Underwear |

|

Jerseys |

|

Jaeger Cap |

|

Ski-cap |

|

Sledging gloves |

|

Working gloves |

|

Instrument gloves |

|

Wool mitts (several pairs) |

|

Snow goggles |

|

Blizz mask |

|

Nose protector |

|

Socks (several pairs) |

|

Towel |

|

Toilet gear |

|

Pocket Medical Kit |

|

Lipsalve |

|

Diary and pencil |

|

Camera etc. |

|

Pillowcase |

|

ANARE knife on lanyard |

|

Watch |

|

Cold/wey Boots (Rock climbing) |

|

Sneakers |

|

|

|

Loan |

|

Down jacket |

|

Down trousers |

|

Sleeping bag inner |

|

Sleeping bag outer |

|

Sleeping bag sheet |

|

Sleeping bag hood |

|

Muklucks |

|

Mukluck inners |

|

Mukluck insoles |

|

Thermal boots |

|

|

|

All this gear is to be packed in such a way that the majority of it can be left in drift proof bags on one of the sledges. This will not only give more room in the caravan but is an essential provision in case the caravan is destroyed by fire. |

|

|

|

Order No. 1 Correction Add : Aim 7 Collecting and sending Meteorological information |