Heights for Tide Gauges : Torres Strait Islands 1973

by David Cook and Jim Steed, 2013, updated 2020

(extracted from Division of National Mapping, Technical Report 19,

Heighting by Vertical Angles, Torres Strait Islands 1973).

A busy shipping route, shallow, congested with numerous rock hazards, strong tidal currents and a five metre tidal range on the eastern side, Torres Strait has always been a hazardous route for ships. Eighteen wrecks were listed during the nineteenth century. In March 1970 Oceanic Grandeur, a 58000 ton tanker drawing 11.8 metres, struck an uncharted rock in one of the shallowest sections of the Great Barrier Reef route, causing Queensland’s biggest oil spill. The rock was demolished by explosives in 1978.

The erratic tides make tidal predictions impracticable. The Department of Transport requested accurate heights, referred to the mainland height datum, at eight sites, where tide gauges would be installed to continuously transmit by radio tidal heights for use by vessels entering the strait. This was achieved by developing techniques to achieve maximum accuracy in observation of vertical angles over long lines across water. One site, at Bets Reef 90km north east of Thursday Island, was considered to be beyond the range of optical observations and was dropped, leaving seven sites :

|

Frederick Island, on the south eastern approach to Cape York |

|

Twin Island and East Strait Island, at the eastern entry |

|

Ince, on Wednesday Island |

|

Hammond Island |

|

Goode Island |

|

Booby Island, at the western entry |

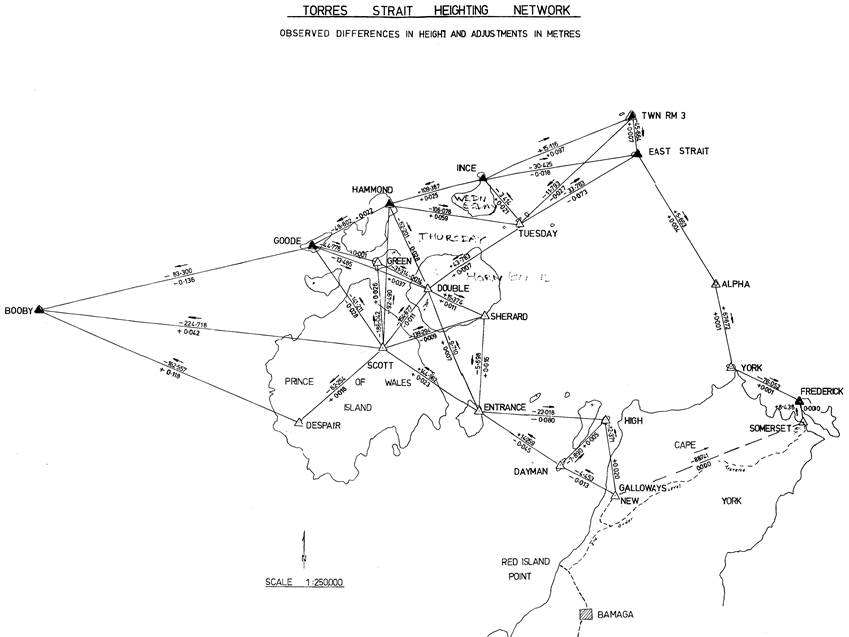

A network of twenty stations were occupied, including one near Bamaga to connect to the Australian Height Datum and another, connected to Bamaga by differential levelling, on the mainland near Frederick Island. The average height closure for twenty triangles was 72 mm and their average perimeter was 32.2 km. The connection from East Strait Islands to Frederick was a single line traverse out to the easternmost triangle.

Early development of the observing technique used low level lines several kilometres long across water, between points of known elevation. It was found that the standard error reached an optimum level after about 24 pointings, over 20 to 25 minutes of time, and this was adopted as a standard set of observations. Wild T3 theodolites were used, with calibration markings added to the alidade bubble.

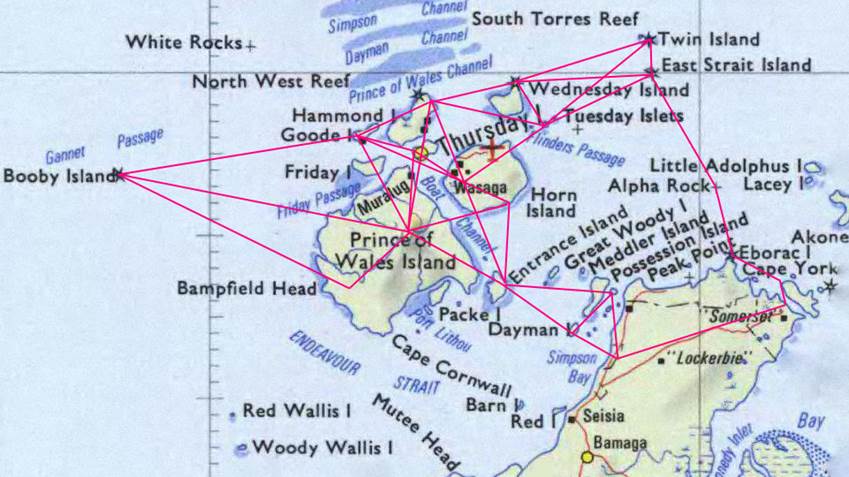

Map of survey area with observed lines

The bubble was read after each pointing, then progressively moved slightly forwards and backwards, using a footscrew, so as to achieve mean bubble readings near zero at the end of each set. To minimise effects of changing refraction each reciprocal sighting was counted down by radio so as to be exactly simultaneous at each end of a line.

Relative standard errors of heights for all combinations of stations at tide gauges ranged from 0.074m to 0.013m. The standard errors of the mean slope for each line ranged from 0.11 seconds to 0.40 seconds; the mean was 0.25 seconds over 36 lines.

The angular standard errors bore no relation to distance; the shortest line, 2.3 km, was not the best and the longest, 33.4 km to Booby Island, was not the worst although it was nearly so due to the poor seeing conditions. The lighthouse next to the trig point was not visible, nor even the island itself; only the light could be seen through the thick haze

Routine geodetic observations were also made, including horizontal angles, EDM distances and some Laplace astro observations, for incorporation in the overall geodetic survey

This project demonstrated that heighting by vertical angles over lines up to fifteen kilometres across water is practicable. Provided that any intervening topography is reasonably symmetrical and there is sufficient wind to minimise layering effects in the atmosphere, the mean observations of slope can achieve standard errors of better than one second.

Stations occupied with observed lines

Each station was occupied for several days and conditions were not always pleasant. Some were infested with sandflies, causing serious problems for some of the observers. Perhaps the least comfortable station was Alpha Rock, a small rock in the middle of the strait, completely devoid of vegetation, with only a small wave-swept shelf for helicopter (#) landings, all shared with hordes of protesting seagulls.

|

|

|

|

Alpha rock accommodation |

Preparing to depart Scott by packhorse |

Photographs by Klaus Leppert, courtesy of his daughter Kathy, may be viewed via this link.

On some small, sandy islands large footprints indicated a necessity for issue of a 303 rifle to repel salt water crocodiles. None were directly encountered but sleeping in the dark became less restful.

A stretch of several hours on the lighthouse maintenance vessel (#), also used for access, pushing at full speed ahead against the tide but remaining stationary, was a memorable demonstration of the conditions for passing ships.

Arrival at Mount Scott, on the summit of Prince of Wales Island, by helicopter, to be followed by departure by packhorse, walking through the deer populated forest then small outboard runabout to Thursday Island provided a reminder of surveying conditions in past years.

(#) During the survey the field party was supported by a Bell 206 JetRanger turbine helicopter chartered from Airfast Helicopters Pty Ltd and flown by French born pilot Alain Le Lec. The helicopter had relatively limited use over a period of a week or so, mainly for positioning personnel and equipment from Horn Island to Hammond Island and then to Twin Island. Afterwards, the the Department of Transport’s 85-feet navigation aids vessel MV Wallach (a 250-ton vessel based at Thursday Island) was used to transport survey parties between the islands (Murphy, 2019‑2020).